When Irrfan got angry with Anup Singh

In a recent book, the filmmaker composes an ode to a friend, an actor whose life enriched the inner world of others

The two on the set of Qissa: The Tale of A Lonely Ghost (2013) (Courtesy Anup Singh)

The two on the set of Qissa: The Tale of A Lonely Ghost (2013) (Courtesy Anup Singh)In one scene in Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost (2013), Tisca Chopra comes charging into a room to push Irrfan’s Umber away from their daughters, her yellow-brown dupatta flies ahead of her, and because of the force of her body, the dupatta touches Irrfan before she does, “the violence created by the colour, not the actual hitting of the cloth, makes Irrfan react in a very frightened, desperate, strong way, he pushes Tisca (who goes flying and hurts her back) with an energy, a violence almost, that I doubt he’d have in any other circumstance,” says filmmaker Anup Singh.

“Anup saab, bahut hi ajeeb roles laateh ho aap mere liye (They are really strange, the roles you bring to me).” For Irrfan, who’d already explored the other rasas of the navarasa (nine emotions) through his myriad characters, the bibhatsa (repugnant) was yet an untouched terrain until Singh brought to him the complex, dark, liminal roles of Umber Singh (Qissa) and Aadam (The Song of Scorpions, 2017). An unwilling and visibly angry Irrfan had asked him, “Is this how you see me?”

The two with camels on the set of The Song of Scorpions (2017) (Courtesy Anup Singh)

The two with camels on the set of The Song of Scorpions (2017) (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Irrfan left the world before Singh could portray him differently — as a dancer in the now-on-hold-indefinitely Lasya (to be trained by Waheeda Rehman) or an elderly film-music composer.

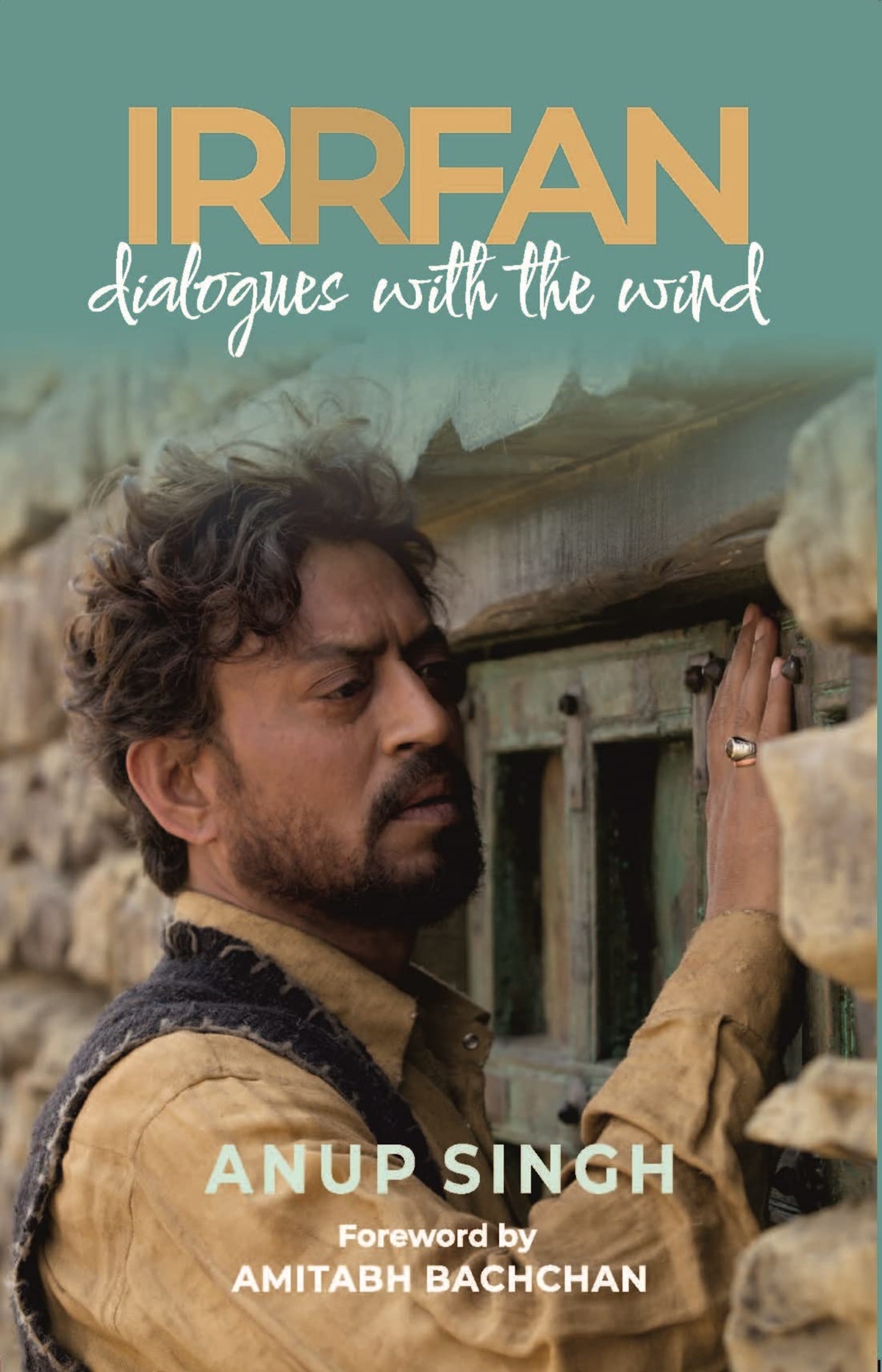

The Geneva-based Singh, 61, whose book, Irrfan: Dialogues with the Wind (Copper Coin), comes two years after the actor’s passing, says, “In him, I saw the rare ability to transform the banalities of our world into grace. Dilip Kumar saab was the only other actor who could transform the banal, routine, evil into a living quality. Even when Irrfan was playing good characters, like in The Namesake (2006), you see the bitterness and resentment, and other elements of what goes into the making of this goodness. Irrfan, who makes your inside world richer, is a spirit, a force, a djinn if you will, that belongs as much to our inner life as to his own. That’s why his passing away hurt us all so much, it felt like something deep within us had died.”

Intuitive and intimate, the book is a reflection in medias res, it unspools in reverse and catches on the linear memory train. The banter of friends; the preparation of an actor; the almost comical chase of the two by a starving bullock; the lump-in-throat passages on the hospital ward, seeing a dear friend in the throes of illness, a life dimming out.

Anup Singh’s book on Irrfan Khan (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Anup Singh’s book on Irrfan Khan (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Everything he did in life would bring him some notion of how to play a said role. He’d, for instance, call Singh up at 3 am to recount driving on a dark road one night, “I couldn’t see the road ahead. Arre Anup saab, what if the road wasn’t there? I drove to feel that sense of fear and then feel the joy of having survived the ordeal and still being alive.” Even when death was nigh, he’d be curious about the process. “Often, he’d avoid taking painkillers, and say, ‘this pain, uncomfortableness, greying of the body, dread of what’s to come is my life at this moment, why should I give it up?’” recalls Singh.

Their paths crossed in the early ’90s. For a one-hour episode for Star TV, in which a strong force upends the relationship between a young woman police inspector (Mita Vashisht) and a criminal. Singh wanted an “extraordinary actor to embody that force”. Vashisht walked in with her National School of Drama classmate. While charting out his movements, the tune Singh thought was playing in his head was being hummed by this new person. Standing next to the camera was Irrfan. On both their lips, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Jee karda mein tenu vekhi jaanwan. After the shot, the lanky young man said, “Aaj ke baad, whenever we’re doing a shot together, please give me a melody.”

Melody, onomatopoeic exchanges and comfortable silences would become their secret code. The next time the two met, years later, for Singh’s sophomore, Nusrat saab would seal the deal again. Inspired from Singh’s grandfather’s life, Umber is an ambiguous and selfish man, who seeks immortality. To help him become Umber, Singh gave Irrfan sounds (Turkish, African and Nusrat saab’s songs and cello renditions of Bach’s Sarabande) and images — Vincent van Gogh’s Grove of Olive Trees (1889), in which, “the wind and the slant of the earth makes the olive tree, to seem, as if it’s just going to start moving, and yet you feel its immense strength in holding onto the earth.” Umber is a brutal patriarch and a doting father, whose show of violence was a mark of his love and “Qissa was very much my and Irrfan’s dialogue with what was happening in the country,” says Singh.

Irrfan never wanted to work with ideas, rather with experience: to experience the other, and himself in different encounters (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Irrfan never wanted to work with ideas, rather with experience: to experience the other, and himself in different encounters (Courtesy Anup Singh)

…Scorpions, too, speaks to our time. Nooran’s (the exiled Iranian actor Golshifteh Farahani) character-mapping elicits the question: “when we breathe in, we have this sense of life, which we keep taking and taking, but every time we breathe out, do we breathe life back into what’s giving us life or do we breathe out the poison we might carry in ourselves?”

The ever-curious Irrfan had questions aplenty: “Who are you? Why are you here? Why did you say that the way you did? That shirt, where did you get it from? That accent, where did you pick it from?” He would almost always respond to stimuli, even to the wind, in a shot. It harks back to his passion for kite-flying (he carried kites to film sets), which gave a young Irrfan, in Jaipur, a twisted arm for life, and a philosophy: “every little pull and release of the kite is a dialogue with the wind, a matter of life and death, that is what was acting”.

For him, the sound under the dialogues — the tone, timbre, hesitation, pause, off-notes — which reveal a character’s secrets was a matter of import and joy. Every space was “a space of exploration”. He’d hesitate at the threshold of a room, scan to see where he’d be comfortable, should he gravitate towards an interesting person or an interesting aroma from the kitchen. He preferred spaces that allowed him free flow into any direction, not those that enclosed him. On the sets too, he’d sit down where he was to perform, feel the earth, lean against a tree or a wall, sleep in the middle of a desert, like a camel, “he wanted to make himself at home everywhere and with everybody”.

“Now, we have very strange ideas about home and country, but the way Irrfan or I thought about home, it’s not borders but our belonging to someone, who thinks about us or even a brief exchange of looks, that makes a home,” says the Film and Television Institute of India graduate, whose own story is fascinating.

In the years before Partition, Singh’s grandfather’s family, in a Punjab village (now in Pakistan), was attacked. By the time his little grandfather gained consciousness, he’d lost both his parents. He was sent off to a relative in Africa, where he “grew up into a strange man, loving but easily nudged into violence”. Singh was born in the Tanzanian capital Dar-es-Salam, but the 1970s, rise of Idi Amin in Uganda and his distrust of foreigners that spread to Kenya and Tanzania, forced the family to out-migrate to Bombay (corruption would make his simple businessman father, years later, to leave India). On the deck of the India-bound ship, between the African sky and wide seas, as he watched a Hindi film — which he often fabulates was Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam (1962), though he can’t recall clearly — the teenaged boy’s “trauma, fear of leaving home, going to a new country” gave way to a feeling of being “a part of a larger sense of home or country — that was cinema”.

Irrfan Khan with Anup Singh (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Irrfan Khan with Anup Singh (Courtesy Anup Singh)

Cinema would redefine his ideas of home into a borderless cosmos, courtesy Ritwik Ghatak’s expansive films, “its wide-angle lens and human-nature relationship brought me a sense of home”, and Irrfan, whom Singh calls a “border being”. Like Toba Tek Singh. “He doesn’t take any sides. Not because of any easy ideas of secularism or neutrality, he wasn’t neutral, as his interviews/talks and film choices evince, but was solely concerned with how to speak with you (even with the non-human, like the camel in …Scorpions) and brought to the world, every time, a new way of speaking with it,” says Singh.

To be “uncertain was almost an ethical need for him. A kind of opening himself up, becoming vulnerable. In a world where we fix people in boxes, and quickly conceptualise everything — Sardar, Maharashtrian, Hindu, Parsi… — the experience of people is lost,” says Singh, “and Irrfan never wanted to work with ideas, rather with experience: to experience the other, and himself in different encounters.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05