Drona Without Award: Two Khel Ratnas Sushil Kumar, Yogeshwar Dutt is not equal to Dronacharya for Vladimer Mestvirishvili

Vladimer Mestvirishvili is the biggest reason for India making a mark in wrestling at the highest level. Several coaches have been feted but the affable Georgian is still to get his due. Meet the man legendary wrestlers call 'God'.

Laado, coach saab or simply, Georgian. Sushil Kumar calls Vladimer ‘God’ while Yogeshwar Dutt describes him as the one who taught the Indians “kushti jeetne ka jazba.”

Laado, coach saab or simply, Georgian. Sushil Kumar calls Vladimer ‘God’ while Yogeshwar Dutt describes him as the one who taught the Indians “kushti jeetne ka jazba.”

It’s Saturday morning at the Chhatrasal Stadium. A septuagenarian moves slowly across the mat, dispensing instructions to young hopefuls. With the verbal cues not proving enough, the teacher, along with his most successful pupil, proceeds to take the pretenders to school. At the end of the three-hour session, the grapplers genuflect and the master responds with a heavily-accented ‘Ram Ram’ after which everyone throws their arms up in the air and yells a one-word battle cry — ‘Jeetenge!’ Many outside the wrestling hall have stayed stuck to the windows all this while, trying to catch a glimpse of ‘Pehelwan ji’ and ‘coach saab’ — two men who have played their part in putting Indian wrestling on the world map.

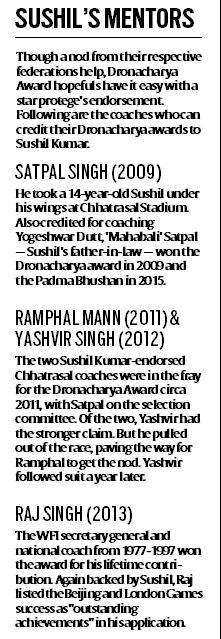

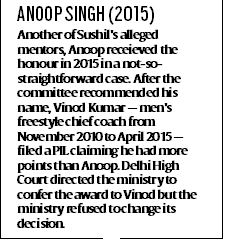

It was in 2008 that Sushil Kumar won a bronze in Beijing, the first Olympic medal by an Indian wrestler since KD Jadhav at Helsinki 1952. Due recognition followed soon enough — the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award was bestowed upon Sushil just a year later. But while many coaches have taken – and, indeed, been given — credit for the grappler’s success in the form of Dronacharya Awards, one man has flown under the radar of the powers that be.

“India ki kushti ko uthaane me ‘Laado’ ka sabse bada haath hai,” says Sushil. “You look at the scenario before and after his arrival. He took the helm in 2003 and our entire team qualified for the 2004 Athens Olympics. Even now, Olympic champions and coaches from several countries come to him for counsel.” Laado, coach saab or simply, Georgian. Sushil calls him ‘God’ while Olympic bronze medallist Yogeshwar Dutt describes him as the one who taught the Indians “kushti jeetne ka jazba.”

Vladimer Mestvirishvili should perhaps be known as the man responsible for the biggest moments in Indian men’s freestyle wrestling for close to one-and-a-half decades. Since his arrival in 2003, Mestvirishvili’s tutelage has resulted in triumphs at world championships, Asian and Commonwealth Games, and three Olympic medals.

After the Sports Authority of India (SAI) did not renew his contract last year at Wrestling Federation of India’s (WFI) behest, Mestvirishvili, now 73, returned at Sushil’s invitation. “I knew he still had a lot more to give to Indian wrestling. I got in contact with Olympic Gold Quest and extended an invitation to him. He accepted immediately even though he had an offer to be the chief coach in Georgia. He turned them down. Isko bohot lagaav ho gaya hai India ki kushti se.”

Mestvirishvili says the Georgia federation tried to woo him not once but three times. “I say no every time because I’ve done that bit. I worked with the Georgian team from 1982 to 1992. I like it here in India.” Fascination with India is only part of the reason. In a 2013 interview with Georgian daily Lelo, he opened up about a promise made to himself. “I like the direction Georgia wrestling is taking. But it’s sad that only now my work is being recognised. I worked for 10 years as the chief coach but nobody said a word of gratitude despite the fact that we had world, European and Olympic champions. We had World Cup winners. When I left my post, I said I would never work in Georgia.”

Slow-burn love

India, thus, served as an adventure. At the end of the 3,200-km journey, Mestvirishvili was greeted by eager employers WFI and a culture shock. One of the many peculiarities that caught him off guard was the self-imposed celibacy observed by wrestlers. “When I first went to the camp, no wrestler was married. This was strange to me but they said wrestlers do not marry. I was told that after their career is over they may get married but not when they are wrestling. I could not understand that.”

Then there was the snake invasion at the SAI Centre in Sonepat. “One time, I killed two snakes in my room. This is so surprising. What am I supposed to do after a snake comes in my room?”

Vladimer and his wife Mareya have been in India since 2003. Pics: Praveen Khanna

Vladimer and his wife Mareya have been in India since 2003. Pics: Praveen Khanna

But once he figured out the keys to a healthy stay in India — “respect the traditions, don’t touch religion, be tolerant” — the Georgian began to see the similarities between the two nations. Early in his stint, with no national camp and no team to work with, Mestvirishvili asked the SAI authorities to deploy him where he could train someone. He was sent to Nidani village in Haryana, where he ended up doing more than just wrestling.

“It was a funny incident. I don’t remember if it was an off day or something but I was in one of the paddy fields of the village and saw this farmer digging in morning. By evening he was still there, still doing it. I went up to him and asked if I could do it. He laughed at me. We Georgians also have fields, so I just started doing it. For the next hour I did his job and I was so happy.”

While wife Mareya has stayed by his side in India, sons Guram and Saigan shifted back to Georgian capital Tbilisi after completing their schooling in Patiala. Mestvirishvili recalls how he would coerce Guram to accompany Sushil and Co. for early morning runs. Sushil remains in awe of how the chubby kid has transformed into a ripped MMA fighter, a development that doesn’t exactly thrill Mestvirishvili.

“MMA is no sport like wrestling. I don’t like it. One punch here and there, you maybe killed. But what can I say! They won’t listen to me. The times are not like when I was growing up.” Perhaps, another feature that keeps him rooted to India. “Here, it is such a good tradition. If parents say something, the children listen.”

Looking ahead

Mestvirishvili would be the first to admit that he never reached his potential as a wrestler. Back in the 70s, Soviet politics ensured the team was dominated by wrestlers from bigger constituents such as Russia. “I have no European championship. No world championship,” shrugs Mestvirishvili. What he does have, though, is an acute mind for aggressive wrestling.

“During his initial days at the camp, he was trying to teach us fitley (leg lace),” recalls Sushil. “One Indian coach said ‘Sir, this move wouldn’t work’. Laado invited him to the mat, attacked his legs and pinned him in a flash.” Incidentally, the same manuevre got Yogeshwar his bronze at the London Games. “He teaches such complex techniques with fine detail. I have greatly benefitted since his arrival,” says Yogeshwar. “Not just me, all the major performances from India have come after he joined the team.”

Sushil adds: “Everybody wrestles with heart in India, from the villagers to us. Daaon maarna sabko pata hai. But he brought the tactics… minute aspects that changed our wrestling.”

The 34-year-old rattles off another anecdote. “I wouldn’t even have qualified for the London Olympics. I lost in the first round at the 2011 Worlds. Couldn’t reach the Asia qualifier final either. I was sitting there dejected, with a pointless 3-4th placement bout ahead. Laado came up to me and told me you have to use all your ‘daaons’ on this Chinese. I outclassed the wrestler, but was still depressed when during the flight home, coach said, ‘something tells me that the guys who finished top two here will help you at Olympics’. Eventually, I defeated the Uzbek wrestler in the quarterfinal, and the Kazakh in the semis. I won the medal, called Laado right away and told him, ‘coach, you are God’.”

No wonder then that a whole new generation is lining up to pick up the tricks. “Now that he is at Chhatrasaal, I have learnt quite a few things. He knows the sport inside out and we are lucky that we can roll with him. I hope he stays in India for a longer period,” says 2016 cadet world champion Deepak Punia.

Mestvirishvili, though, offers a candid assessment of the current state. While he has his own amusing parameter to prove that wrestling has grown — “When I came in 2003, two-three people had a car. Now everybody in the team has a car.” — he admits India is far from being a wrestling superpower.

“Individually, everybody is great. They are great in nationals, trials and competitions but when you want a team, it’s not the one a coach likes. When you form a team, you want it to be strong and together but here it is not the case. A wrestler has a problem but he wins trials and becomes the best in India, everyone is happy. Finally, in the team, each wrestler has problems and together it becomes a big problem. The younger generation needs to be made mentally solid to get medals.”

He is doing his bit, one gruelling session at a time. Sushil is confident that his six-month stay will be extended and Mestvirishvili is more than happy to stay at his home away from home. “Indian wrestlers, sab achcha bachcha hai. They have the talent to win anywhere and I want them to do it. I do not need anything apart from my salary,” he says.

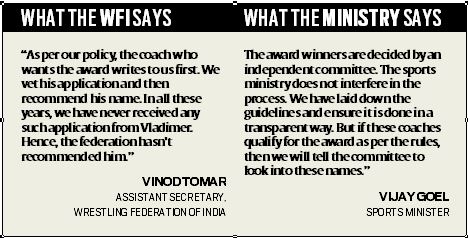

There are a few, though, who believe he should be awarded the Dronacharya. “He should have got it by now. There is no reason to not give it to him,” Kuldeep Singh, chief coach of the Indian Greco-Roman team, says. As with the Georgian team of the 80s, Mestvirishvili has produced world, Asian and Olympic champions in India. A word of gratitude would do him no harm.

Photos