The train is yet to come, and the district rambles along on a road past jams. There are schools now but no ‘masters’; few jobs but many gods. The local corn has given way to eucalyptus, while on one field grows a junkyard of discarded cars. E P Unny on the many dichotomies of India’s poorest district, and the Adivasis in the middle

Deprived and defiantly good-looking, this is the kind of locale where a Pather Panchali could have been shot. Only, Satyajit Ray would have had to go elsewhere to film the classic train scene — the celebrated extra long shot where Durga and Apu amble along the windswept Kaash grass to finally sight the sign of colonial progress. Decades after the 1955 film based on the 1928 Bibhutibhushan novel, here is an eastern Indian district with no rail.

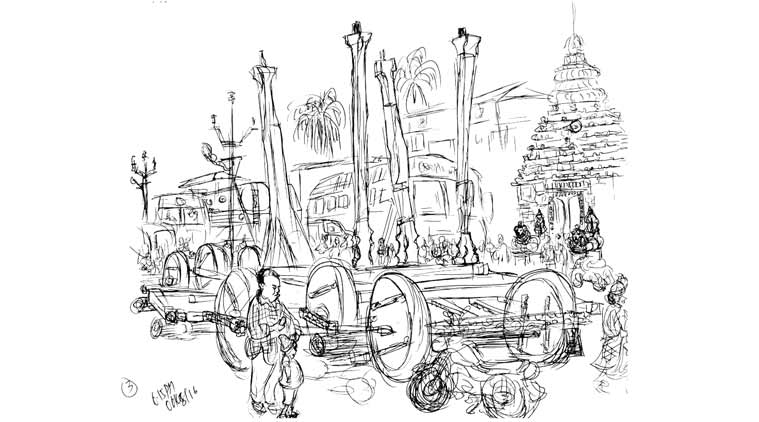

No parking ticket for the temple chariot in centre of town

No parking ticket for the temple chariot in centre of town

The sole access is the road, and that curves up across the ghats to reach the 2,000-feet plateau. You don’t have to wait for long to see why growth initiatives plateau out in these parts. A truck rams into an oil tanker and the traffic stops. “JAM!” cries out your excited cab driver as he steps out to continue his virtual journeys through the cellphone. He has two of them. Looks as though he has budgeted for breakdowns. Most locals have. No anger, as in the city.

Dr. Poma Tudu I.A.S. heads the District Rural Development Agency- motivated by her mother, the first woman from the tribal family to go to school; At home in Umerkote younger Bengalis can’t read and write only speak their first language; Meghnad Jani, a young school teacher, already worried about his inadequate pension; Children in these parts seem to be mostly on human prams- being carried around by men and older children

Dr. Poma Tudu I.A.S. heads the District Rural Development Agency- motivated by her mother, the first woman from the tribal family to go to school; At home in Umerkote younger Bengalis can’t read and write only speak their first language; Meghnad Jani, a young school teacher, already worried about his inadequate pension; Children in these parts seem to be mostly on human prams- being carried around by men and older children

The famously fatalistic India? Not quite. Commuters are out negotiating to shift to smaller vehicles which try and slip through the snarl, eventually creating sub-blocks. There is an army of firemen at work because the tanker is carrying hazardous stuff. No cops in sight.

Mother Teresa Public School in Nabarangpur town: Students rehearse for I-Day parade

Mother Teresa Public School in Nabarangpur town: Students rehearse for I-Day parade

Three days later, on your way back, you find the tanker removed, and the broken-down truck still there hogging a good part of the road. The firemen operated exactly like the helpless hopping commuters and somehow found the first way out. Did their part of the job and left.

The place has evidently seen many such half measures well begun in an earlier era and abandoned without much ceremony. The municipal town seems to be work in regress. Enough buildings to house the district officialdom but not one without peeled walls, the collectorate included. No tidying up even in honour of the Independence Day just a week ahead. The only sign of fresh paint is on road signs that caution you about the school ahead. Many new schools have come up since 2006 thanks to the Right To Education (RTE) Act. Some of course don’t open because “there is no master”.

A junkyard in the making in the vast green vacant lands of Murtuma

A junkyard in the making in the vast green vacant lands of Murtuma

The ones that are actively staffed coach students who go on to do “plus two science” and “plus three arts”. Half an hour with a teacher in a torn T-shirt and you know what kind of basic education is being imparted. No wonder even those who make it to the Industrial Training Institute in Umerkote aren’t quite employable.

In any case, where are the jobs? The biggest industrial employer in sight is Mangalam Timbers, which has been around for 30 years making fibre boards for furniture.

At Umerkote’s Monday mandi, products organic and recycled

At Umerkote’s Monday mandi, products organic and recycled

You need an extra strong spinal column to get to the plant in the first place. Even the occasional Naxalite sighted hereabouts wouldn’t risk the back-breaking 3-km-long panchayat road, quips a security guard at the factory gate.

Umbrellas are everywhere. No one seems to take the monsoon for granted including the farmers; Fishmonger says he is a businessman. Fellow Adivasi catches fish in the dam

Umbrellas are everywhere. No one seems to take the monsoon for granted including the farmers; Fishmonger says he is a businessman. Fellow Adivasi catches fish in the dam

The town’s roads seem to be jinxed. Right in the middle of the Nabarangpur main road, for days on end, a temple chariot rests long after the festivities are over, till it is ritualistically dismantled. People have one more reason not to complain because the matter is religious. Besides their own pagan deities, Adivasis in this predominantly tribal district freely worship the traditional Hindu pantheon, or go to church if they have been baptized.

Projectionist Praful Kumar Patnaik at Sri Lakshmi Talkies, the district’s only cinema hall

Projectionist Praful Kumar Patnaik at Sri Lakshmi Talkies, the district’s only cinema hall

Every other month there is a festival to look forward to. Rath yatra is just over and Dussehra is keenly awaited and then come Christmas and ‘Happy New Year’. Per capita faith is very high here. So much so that devotees regularly travel out to Andhra Pradesh’s Tirupati and Kerala’s Sabarimala.

A packed spiritual itinerary that leaves you with little leisure. Perhaps why there is just one movie hall in the whole district, Sri Lakshmi Talkies — hardly patronised. The projection room is quite a sight — click and portal digital projector housed in brick and mortar about to come apart.

Mid noon in the middle of nowhere in interior Nabrangpur comes the comforting din of this old world rice mill.

Mid noon in the middle of nowhere in interior Nabrangpur comes the comforting din of this old world rice mill.

You step out of the movie hall and wonder whether you have gone colour blind. Despite the rains, the town looks dusty and relentlessly grey. It is when you drive out that the ‘rangs’ of Nabarangpur come alive. Closer to their tribal habitat, locals smile a lot more, speak even less and patiently pose for doodling, which takes a while. They seem to be more at home with the slower sketch pen than the snappy camera.

Only house built under a government scheme in this tribal village has a non-tribal motif

Only house built under a government scheme in this tribal village has a non-tribal motif

Men take the cattle out, women are in the paddy or maize fields, and the kids are having a great time. They are all the while being carried around most ergonomically. Besides the inherent ease, indigenous design has picked up the flair to improvise. A motor oil can is cut and shaped into a wheeled toy. Used edible oil containers are recycled into sieves and kitchen utensils, in sizes and shapes incredibly standardised.

Indravati Dam: Farmer remains poor not for want of water; Routine traffic jam on the ghat road to Nabrangpur

Indravati Dam: Farmer remains poor not for want of water; Routine traffic jam on the ghat road to Nabrangpur

Hard to believe it is done with hand. Contrast this with the carpentry and masonry that suffocate you in almost every kind of building that is coming up in town. In a district with 56 per cent tribal population, there is much eagerness to impose external constructs on Adivasis, not to extend their lifestyle.

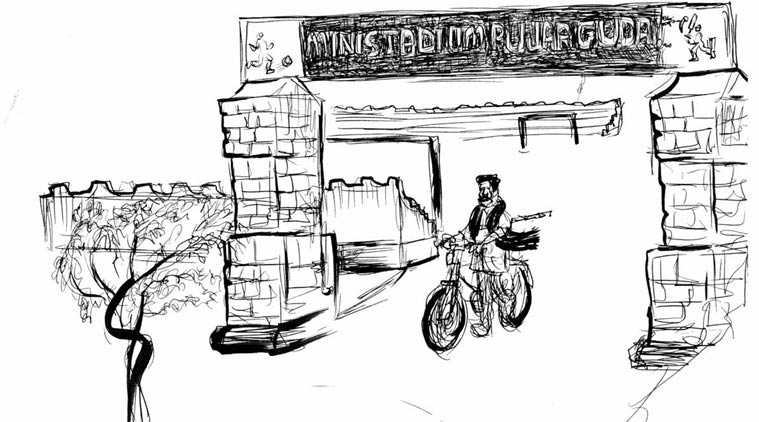

A gateway and an abandoned ground meant to promote local sporting talent.

A gateway and an abandoned ground meant to promote local sporting talent.

In the villages, lives are lived without compound walls, and neighbourhoods are held together by a certain architectural cohesion. The small cluster of mud houses in Majhiguda is one such whole, but for a lone structure that sticks out. Built under the Indira Awaas Yojana, the building has been modelled by the sarkari builder on an approved concrete mould.

For good measure, the builder has thrown in an Om motif. Not that the Adivasi has any faith issue over it, it is a needless imposition of authority, like a rubber stamp duly affixed. All of which would have been pardonable if the roof hadn’t cracked. The welfare beneficiary has had to go back to the locally baked earth tiles to plug the leak. This is as telling a snub as the authorities can get, not that they care.

Mangalam Timbers: An early sign of industrialisation, no longer reassuring

Mangalam Timbers: An early sign of industrialisation, no longer reassuring

Unlike the silent indigenous lot, the Bengalis of Umerkote are vocal. Resettled here as part of the Dandakaranya project, these one-time refugees have over the years become part of the landscape, which itself isn’t exactly changing for the better. Monsoons have been erratic and the cropping pattern is shifting from maize to ‘Nilgiris’ (read eucalyptus).

The local corn variety was once considered among the best in Asia, says Mridul Kanti Mandal, a seasoned cultivator, and he would love to switch back with a little help from the government. Predictably no response yet. Somebody will wake up when the environmental impact of monoculture eucalyptus plantations hits between the eyes.

Farmland owner Jitu Kumar Nayak lives happily among Adivasis, many his farm hands.

Farmland owner Jitu Kumar Nayak lives happily among Adivasis, many his farm hands.

More immediate than the agro disaster in the making is the danger of a junkyard of discarded vehicles coming up in these vacant green lands. After a day out with a million such developmental disconnects, Dr Poma Tudu, the project director of District Rural Development Agency, is back in her office and smiling.

Hailing from the Mayurbhanj tribal belt, she is the walking advertisement of indigenous culture. Donning a locally woven, vegetable dyed shawl, she points out the stylized motifs on it drawn from everyday life. A graduate from Delhi’s Lady Hardinge Medical College and a 2012-batch IAS officer, she didn’t have to look far for a role model. Her mother is the first woman in her tribal family to go to school, college and on to a job in RBI. Quite a leap in one generation.

The sole surviving house in its original form built to resettle a Bengali family in Murtuma village.

The sole surviving house in its original form built to resettle a Bengali family in Murtuma village.

This newspaper has been focusing on Nabarangpur for a whole year now and would wait for such big success stories to happen here. Meanwhile, we’ll ask little questions such as: Who has the mindset problem, Adivasis or the rest of us?