With half an hour left before boarding my flight from Boston to Orange County, California, I tuned in to Nintendo’s Direct with no expectations. Sure, it was the showcase marking the 40th anniversary of Mario, but as with any Nintendo event, neither I nor anyone else really knew what to expect. But Nintendo had plans of its own.

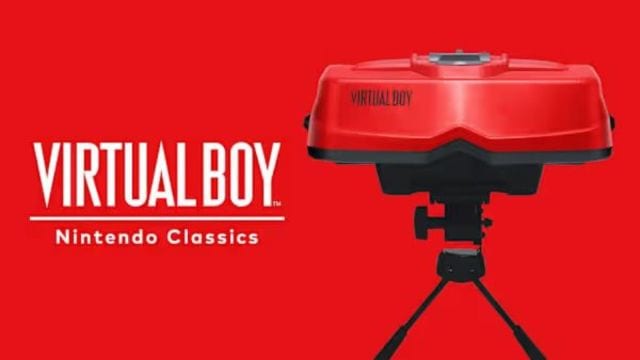

Out of nowhere, the company revealed that Virtual Boy games would be coming to Switch Online in February next year. That alone was surprising until they announced something even bigger: a new Virtual Boy headset designed to play those retro titles. Best of all, you will be able to slide in your Switch 1 or Switch 2 screen directly into the accessory to play.

“A Virtual Boy is coming back… oh boy”. Those were the first words I muttered as I sat glued to Nintendo Direct.

I bet you might not be familiar with the Virtual Boy or when it first hit the market. As someone who is a Nintendo historian at heart (or at least that’s what I like to call myself), memories of the Virtual Boy started flashing back when I actually got the chance to try the console in Tokyo earlier this year.

While many of you may have experienced virtual reality, or at least heard of it, Nintendo actually jumped into VR decades ago with the Virtual Boy. In fact, the Virtual Boy just celebrated its 30th anniversary last month. I would say it was a bold experiment in stereoscopic 3D gaming that ultimately became Nintendo’s least successful game system ever. So, I was a bit surprised to see that Nintendo is actually bringing the Virtual Boy back to a market no one saw coming.

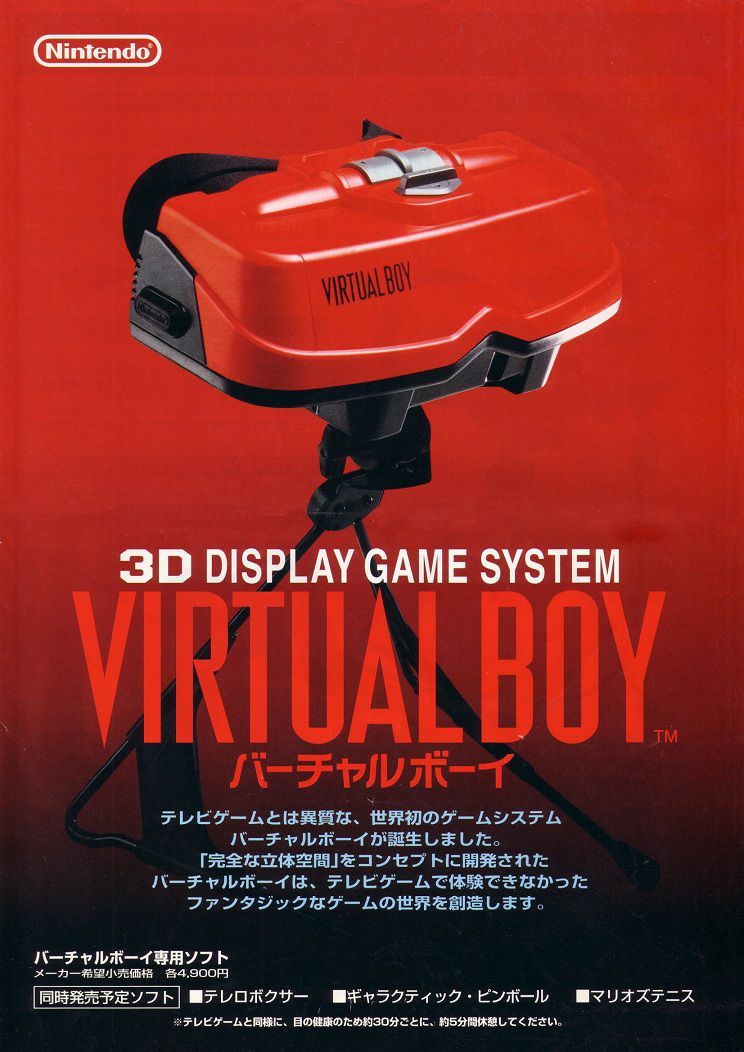

It was on August 14, 1995, that Nintendo first released the Virtual Boy in the United States. At launch, there was a lot of hype surrounding the Virtual Boy in both Japan and the US. In typical Nintendo fashion, the system was different and unlike any other video game console on the market.

A 1995 Japanese ad for the Nintendo Virtual Boy. (Image Credit: Nintendo)

A 1995 Japanese ad for the Nintendo Virtual Boy. (Image Credit: Nintendo)

The Virtual Boy was the creation of the late Gunpei Yokoi, who contributed immensely to Nintendo’s success. He revolutionised game control in the 80s by inventing the cross-shaped D-pad, which replaced the joystick. Yokoi also created the iconic Game Boy, helping to bring portable video game systems into the mainstream. It’s no wonder he also spearheaded the development of Nintendo’s iconic titles like Metroid and Super Mario Land.

Story continues below this ad

All of the early success made Nintendo confident about Yokoi’s ability to work on the next-big thing at the Kyoto-based company: the Virtual Boy. Yokoi, who was the head of Nintendo’s R&D1 department, had been working on the VR technology for some time.

Contrary to popular belief, the core technology behind Virtual Boy was developed not by Nintendo, but by a now-defunct American company called Reflection Technology.

In 1985, they worked on a device called Private Eye, which resembled something close to Google Glass more than a traditional VR headset. It featured a 3D stereoscopic head-tracking display using a tiny 720×280 pixel screen in front of the right eye, with a Scanned Linear Array of LEDs to create a red, single-color 3D effect. A confident Reflection Technology later demoed the system with a tank battle game and pitched it to different companies including toy companies Mattel and Hasbro, who ultimately passed on the technology.

From the beginning, Yokoi set out to create something totally unique and different using VR. However, the real challenge was keeping the system’s price affordable, a problem that still affects most modern VR hardware. Once Nintendo gained access to Reflection Technology, they retained the red-only display system, and 3D graphics were largely created using wireframes, rather than the polygon-based approach used by most other consoles. To build powerful hardware, Nintendo used a 32-bit RISC CPU chip.

The development of the Virtual Boy’s hardware began with the development of a high-resolution portable display called the scanned linear array (SLA), invented by Reflection Technology of Waltham, Massachusetts in 1986 and patented soon after. (Image credit: Nintendo)

The development of the Virtual Boy’s hardware began with the development of a high-resolution portable display called the scanned linear array (SLA), invented by Reflection Technology of Waltham, Massachusetts in 1986 and patented soon after. (Image credit: Nintendo)

Initially, the plan was to make the Virtual Boy head-mounted, using the core technology’s head-tracking abilities. However, Nintendo quickly backpedaled on this due to liability and health and safety concerns, particularly regarding motion sickness and the development of lazy eye problems in children.

Story continues below this ad

The console was housed in a red visor mounted on a collapsible metal stand. In its marketing materials, Nintendo called the Virtual Boy “portable” since it was self-contained and could run on batteries. However, unlike other portable systems, it couldn’t be played on the go, for example, on a train or in a car, because the stand had to rest on a flat surface like a table.

At the time, Nintendo touted the Virtual Boy for its 32-bit processor, similar to the recently announced Sony PlayStation – indeed, a powerful console by modern standards. However, the graphics didn’t match what consumers typically associated with the term “32-bit.” Instead, the Virtual Boy’s visuals were created using rows of red LEDs. That was just one of many differences between the Virtual Boy and other consoles of that time.

To experience stereoscopic 3D graphics, consumers needed to place their face into the Virtual Boy’s visor, where each eye would receive a slightly different image, creating the illusion of depth. The design of the Virtual Boy was reminiscent of other VR headsets that were all the rage in the US. Remember, this was a time when the concept of virtual reality was just starting to gain traction in pop culture, thanks to Hollywood. However, the experience delivered by the Virtual Boy was different. Instead of offering a true first-person, virtual-reality experience, most of the Virtual Boy’s games were standard in design, with only basic depth-of-field 3D effects added.

On one level, the Virtual Boy did promise a 3D world that consumers could experience through a head-mounted visor and play video games in, but it was far from a true virtual reality headset. Nintendo was hopeful that the Virtual Boy would be a huge hit, but the opposite happened. Consumers didn’t understand what the Virtual Boy was or what Nintendo was attempting to do. At $180, the Virtual Boy’s sales fell far short of Nintendo’s own estimates, and the company discontinued the device in less than a year.

Story continues below this ad

Looking back now, the Virtual Boy felt like an experimental device, aiming to give consumers a taste of virtual reality: Nintendo-style. It was a pretty cool gadget, a video game system that tried to introduce VR to the masses. But not every experiment works, and the same was true for the Virtual Boy.

Perhaps what went wrong with the Virtual Boy was, of course, the messaging: the console confused many consumers. But the bigger issue was that Nintendo hadn’t figured out a killer app that would convince people to buy it. Was it the 3D graphics, the hardware, or the games? Ironically, what should have been Nintendo’s core strength-the games-were less addictive and barely available at launch. In total, only fourteen titles were released before the Virtual Boy was discontinued, all within the span of a single year.

One game that did stand out was Virtual Boy Wario Land, an addictive 2D platformer that, ironically, made minimal use of the system’s 3D functionality. In Japan, the final Virtual Boy games were released on December 22, 1995. In the United States, the last title was 3D Tetris, released on March 22, 1996.

Not only consumers, but retailers too gave a muted response to the Virtual Boy. Nintendo struggled to market the console the way it was originally intended. Because it displayed 3D graphics, Nintendo couldn’t show screenshots in print magazines, and game trailers on television failed to convey the messaging. That’s still a major challenge with VR and mixed reality headsets today: how do you effectively market content made for devices that bring immersiveness at the center?

Story continues below this ad

As was the case with the Virtual Boy, nothing really worked well enough to make the world take notice or get excited about the system. However, over the years, Nintendo has significantly evolved its marketing strategies and is now seen as a benchmark in the industry. The same can also be said for Apple.

By 1996, Virtual Boy hardware and games were being sold at dirt-cheap prices, with collectors picking up units for as little as $30. Meanwhile, retailers had begun offering games for $10 or less. In the end, Nintendo sold only about 770,000 Virtual Boys worldwide before pulling the plug. Undoubtedly, the Virtual Boy was an ambitious system that aimed to change how people play video games, but it ultimately became one of the biggest flops in gaming history.

The failure of the Virtual Boy led to Yokoi’s exit from Nintendo; he left the company just over a year after its release and was tragically killed in a car crash in 1997. While many blame Yokoi for the Virtual Boy’s shortcomings, he never intended the version that was released to be made public. In fact, Yokoi wanted to spend much more time refining the Virtual Boy to address the trade-offs that were quite visible.

In the US, Nintendo had partnered with Blockbuster to rent out Virtual Boy systems so that consumers could try it for themselves, a differentiated strategy to get around the difficultly of conveying the system’s 3D effect in print and TV advertising. (Image credit: Nintendo)

In the US, Nintendo had partnered with Blockbuster to rent out Virtual Boy systems so that consumers could try it for themselves, a differentiated strategy to get around the difficultly of conveying the system’s 3D effect in print and TV advertising. (Image credit: Nintendo)

While many had forgotten that the Virtual Boy even existed, its revival, announced during Nintendo Direct this week, brings back memories of the stereoscopic game console that never quite became the virtual reality device the Japanese gaming giant had envisioned. It was certainly a strange 3D system that played games, but it was far from a true VR headset. This continues to suggest that, somewhere within Nintendo, there’s still hope that the company will one day create a VR device ready for mass consumption. And while the Virtual Boy was never truly meant to be that device, it did carry early traces of VR technology.

Story continues below this ad

Nintendo’s reincarnated version of the Virtual Boy looks almost identical to the original system. However, the key difference is that it now works with the Nintendo Switch or Switch 2, which fits into the headset to play the classic black-and-red 3D games. There’s also $25 affordable cardboard version available for playing the games. As for the games themselves, they will be included as part of the Nintendo Switch Online subscription service. Still, $100 is a steep price for the new Virtual Boy accessory, especially when you factor in the additional cost of the subscription service. And if you are eyeing the Switch 2, that alone costs over $500 without even including any games.

VR is an interesting technology, but it hasn’t caught on the way many companies had hoped. Even Apple, much like Nintendo in 1995, has experienced a commercial flop with the Vision Pro, though in Apple’s case, the device comes at a staggering cost of $3,500. It makes me wonder whether Nintendo is genuinely interested in VR technology and might be considering another experiment with a dedicated system. That remains to be seen, but the new Virtual Boy accessory does suggest that Nintendo is at least curious about VR, though many believe it might simply be a nostalgia play. I would beg to differ.

Over the years, Nintendo has shown interest in immersive technology. In 2019, it launched Nintendo Labo VR, a cardboard kit for the Switch that let players enjoy a variety of VR games using DIY cardboard accessories. Its 3DS system also featured a built-in 3D display and included AR games at launch. In fact, Nintendo has done quite a bit with augmented reality. If you have ever visited Universal’s theme parks, the Mario Kart ride uses an AR visor to project overlaid experiences during the ride. Perhaps the closest Nintendo has come to bringing AR to the masses is Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit, a game that uses a physical RC car equipped with built-in AR effects.

But despite its problems, the Virtual Boy was a clear indication that Nintendo supported a vision where VR could take video games to a more immersive level. It unfortunately didn’t land at the time, but Nintendo’s technologies did leave an impression on subsequent systems.

Story continues below this ad

I believe VR as a technology still holds a lot of potential. There’s something undeniably powerful about it, as Apple’s Vision Pro has demonstrated. However, I remain hopeful about what Nintendo might do differently with VR, a company that has always prioritised fun, playful, user-centric interactions over chasing raw graphical power.

A 1995 Japanese ad for the Nintendo Virtual Boy. (Image Credit: Nintendo)

A 1995 Japanese ad for the Nintendo Virtual Boy. (Image Credit: Nintendo) The development of the Virtual Boy’s hardware began with the development of a high-resolution portable display called the scanned linear array (SLA), invented by Reflection Technology of Waltham, Massachusetts in 1986 and patented soon after. (Image credit: Nintendo)

The development of the Virtual Boy’s hardware began with the development of a high-resolution portable display called the scanned linear array (SLA), invented by Reflection Technology of Waltham, Massachusetts in 1986 and patented soon after. (Image credit: Nintendo) In the US, Nintendo had partnered with Blockbuster to rent out Virtual Boy systems so that consumers could try it for themselves, a differentiated strategy to get around the difficultly of conveying the system’s 3D effect in print and TV advertising. (Image credit: Nintendo)

In the US, Nintendo had partnered with Blockbuster to rent out Virtual Boy systems so that consumers could try it for themselves, a differentiated strategy to get around the difficultly of conveying the system’s 3D effect in print and TV advertising. (Image credit: Nintendo)