Rich as well as lower classes moved away, but AAP retains support of poorest strata

The combined demographic weight of the rich and middle classes in Delhi means no party can win in the Capital after losing significantly among them.

With welfare schemes, Arvind Kejriwal, then Delhi’s Chief Minister, came to be dubbed as the family man who understands the woes and aspirations of ordinary families. (Express photo/ Praveen Khanna)

With welfare schemes, Arvind Kejriwal, then Delhi’s Chief Minister, came to be dubbed as the family man who understands the woes and aspirations of ordinary families. (Express photo/ Praveen Khanna)

The Aam Aadmi Party’s (AAP’s) entry into electoral politics in 2013 reconfigured Delhi’s political space in many ways. Not only did it restructure a largely bipolar political space (Congress and BJP) into tripolar, but also marked a significant shift towards class-based political preference. The AAP’s political agenda as well as electoral promises captured the imagination of people occupying the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

As the party formed the government on its own in 2015, it crafted and launched a slew of schemes – from free electricity and water to free bus rides for women – directly benefiting working classes and ordinary families. Focused attention and enhanced spending on education and healthcare to improve quality of educational and healthcare facilities – what the working and middle classes are most concerned about – supplemented a variety of welfare schemes.

With these welfare schemes, Arvind Kejriwal, then Delhi’s Chief Minister, came to be dubbed as the family man who understands the woes and aspirations of ordinary families.

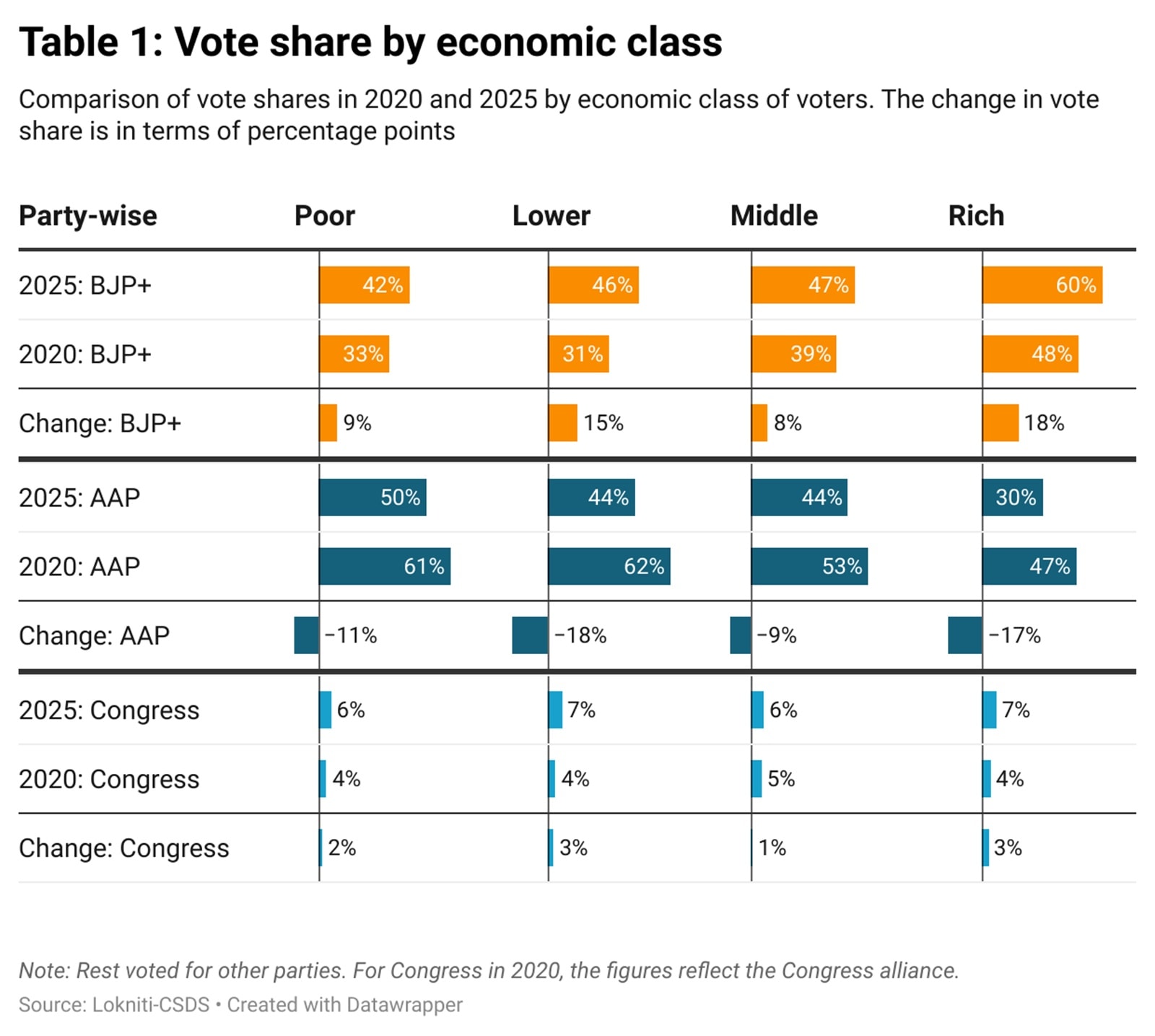

In the last two Assembly elections (2015 and 2020), as the CSDS data shows, the AAP received a considerable chunk of votes from across the class spectrum, but it was still voters from the lower economic strata who supported it far more than others (Table 1).

Table 1: Vote share by economic class.

Table 1: Vote share by economic class.

However, the results of the 2025 Assembly elections show that the AAP lost more than two-thirds of the seats it had bagged in 2020.

Did the AAP perform quite badly in its core constituency, that is the disparate working classes? Findings of the CSDS survey indicate that it lost support across the class spectrum in 2025, albeit in varying proportions.

Compared to 2020, the AAP’s support among the poor fell by 11 percentage points. Its vote share among the lower classes declined even more sharply – by 18 percentage points. Although the AAP saw a section of the middle-class voters also move away from it, it was among the rich that the party lost hugely. The combined demographic weight of these two economic classes in Delhi is such that no party can dream of being in power in the Capital after losing significantly among them.

In a largely bipolar contest like Delhi’s, the incumbent’s loss is a direct gain for the main rival party. And, sure enough, the BJP gained support from across the class spectrum, with the middle and upper classes throwing their weight behind it.

However, the AAP still has a substantial base among the people at the bottom of the economic pyramid. In brief, it may have lost the elections but it is not completely out of people’s favour.

Alam is an Associate Professor at CSDS.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05