Most Delhi voters see welfare schemes as a right, but looked for more

30% respondents feel freebies do not bring substantial change in lives of individual households, but 60% argue that welfarism is a civic right

The vote distribution between the BJP (45.5%) and AAP (43.5%) clearly shows that the electoral battle was not entirely about who brings what. (Express photo/ Tashi Tobgyal)

The vote distribution between the BJP (45.5%) and AAP (43.5%) clearly shows that the electoral battle was not entirely about who brings what. (Express photo/ Tashi Tobgyal)The popular perception that the welfare schemes proposed by the BJP and AAP eventually determined the outcome of the Delhi Assembly elections is not entirely incorrect. It is true that welfarism emerged as a decisive electoral issue, with the BJP relying on civic concerns and public delivery and the AAP trying to evoke its past performance, especially in education and health.

This competitive welfarism, however, cannot be exaggerated to draw a simple conclusion that the BJP’s guarantees were more substantial and reassuring. The vote distribution between the BJP (45.5%) and AAP (43.5%) clearly shows that the electoral battle was not entirely about who brings what. Instead, voters were looking for political resolve to address fundamental economic issues.

The CSDS-Lokniti survey, broadly speaking, captures two core features of this.

First, that Delhi voters take the idea of “labharthi (beneficiary)” very seriously. It seems they looked at the promised policy packages carefully and made a realistic assessment of the proposed mechanism to deliver these policies. Table 1 clearly shows that an overwhelming majority of beneficiaries credited the AAP government for waiver of their outstanding water bills, free electricity, and mohalla clinics.

Table 1: How beneficiaries attribute credit for government schemes.

Table 1: How beneficiaries attribute credit for government schemes.

Table 2, however, gives another picture. It shows that beneficiaries of the AAP government’s schemes preferred to vote for the party’s candidates. However, the dissatisfied section of Delhi’s voters, who could not get access to these schemes, eventually decided to vote for the BJP. It simply means that the voters also behaved in a highly professional manner.

Table 2: Vote choice by beneficiary status.

Table 2: Vote choice by beneficiary status.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, Delhi’s voters did not envisage welfarism as a long-term solution to deal with structural problems such as growing unemployment and economic disparity. The survey shows that a significant majority of respondents believed that one-time welfare grants were important to survive in the present context of economic uncertainty, but that infrastructure development such as building better roads and railways was more important for the nation’s overall development than supporting the poor through one-time schemes (Table 3).

Table 3: Is building better public infrastructure more important for national development than welfare schemes?

Table 3: Is building better public infrastructure more important for national development than welfare schemes?

This critical assertion underlines the fact that there is a strong desire to have a dignified, self-sustaining economic life.

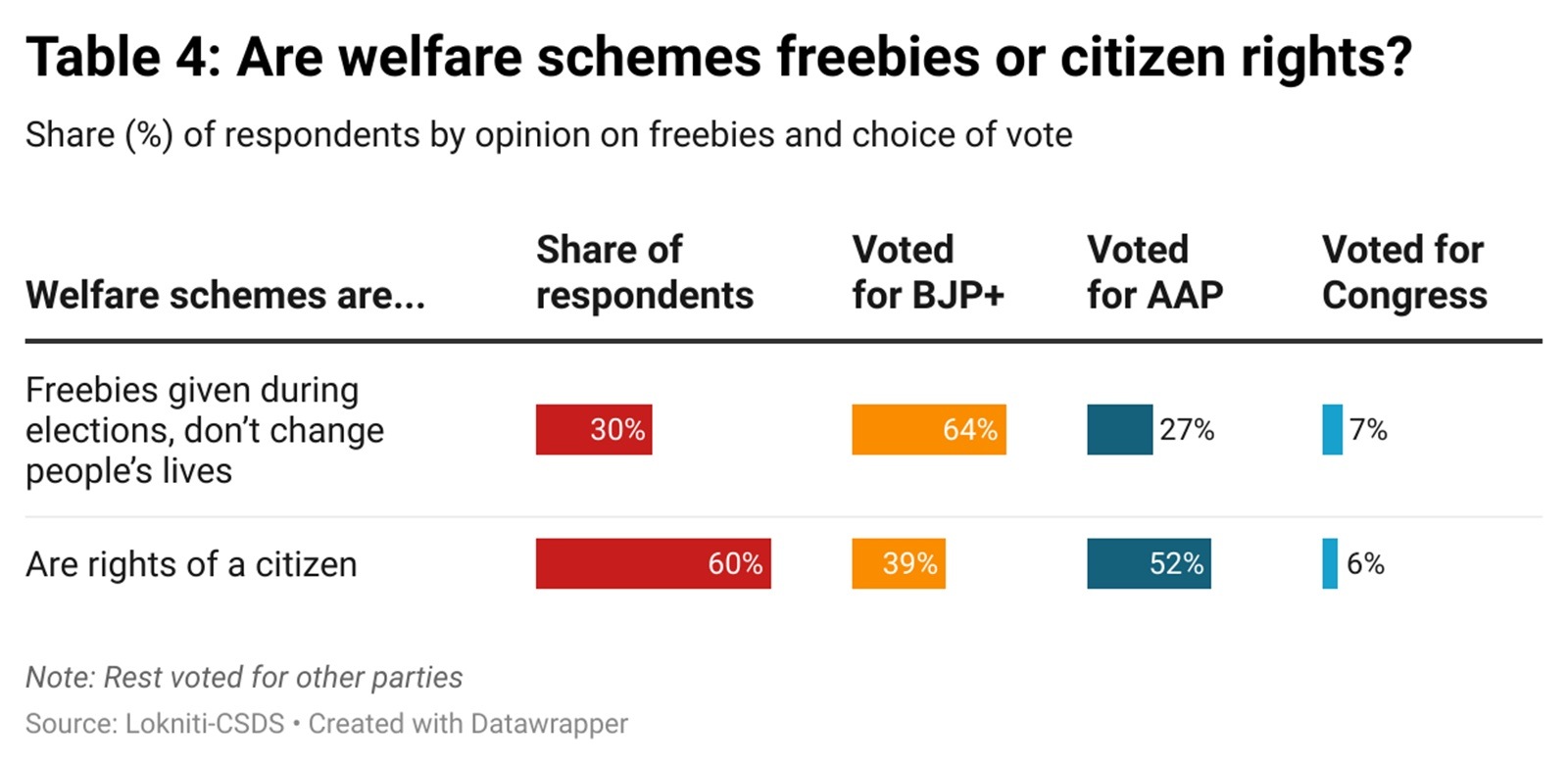

Table 4 is relevant in this regard. Around three of every 10 (30%) respondents claim that freebies do not bring substantial changes in the lives of individual households. However, a decisive majority – six of every 10 (60%) – argued that welfarism is a civic right; hence, assistance given by the Centre or state governments should not be seen as a kind of political benevolence.

Table 4: Are welfare schemes freebies or citizen rights?

Table 4: Are welfare schemes freebies or citizen rights?

This finding underlines an important critique of the emerging form of governance, which might be described as a charitable State model. This model is based on an assumption that the task of the State is to develop the capabilities of citizens so that they can compete and survive in the free market-driven economic sphere. The one-time welfare schemes are supposed to make citizens capable, efficient and above all responsive. The official thesis of ‘responsive government, responsive citizen’ is based on this principle.

Our data, however, clearly shows that the majority of voters do not want to embrace the given identity of responsive citizens. Instead, they assert their constitutional identity as dignified Indians to reclaim welfarism as a fundamental right.

Ahmed is an Associate Professor at CSDS.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05