Why Khanna probe has action not-taken report

On Monday, the Railway Board will meet to finalise an action taken report (ATR) on the Justice G C Garg commission report on the 1998 Khanna...

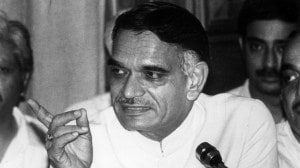

On Monday, the Railway Board will meet to finalise an action taken report (ATR) on the Justice G C Garg commission report on the 1998 Khanna rail accident that killed 210 people. The meeting, as usual, will be chaired by the board’s chairman, R K Singh. What is unusual, however, is that the Garg report severely indicts the Directorate of Track Procurement for the accident, which was then headed by R K Singh.

A series of letters that Singh, who was then executive director, Tracks Procurement, signed allowing relaxations in quality specifications of the rail track had formed the basis of the commission’s conclusion: ‘‘I would hold Railways in the Directorate of Track Procurement to be primarily responsible for not ensuring production of quality rails, for granting relaxations in the production of rail steel and rails and for not making available USFD machines for a long time to the field staff.’’

Monday’s meeting itself comes a little too late. It is mandatory for the Railway Ministry to table the report and the ATR in Parliament within six months of its submission— January 15. Parliament, however, will adjourn on December 23.

The report does not name Singh but details how the railways ‘‘casually’’ continued to give relaxations in quality specifications set by itself, ‘‘putting on tracks such sub-standard or defective rails that would endanger the safety of travelling public.’’

Despite repeated attempts, Singh was not available for comment. Railways’ official spokesperson, too, refused to comment.

Singh—who ordered the purchase of the track that cracked causing the accident—later superseded 16 others in the department to become the board chairman in 2003. Letters signed by Singh granting relaxations to the public sector Bhilai steel plant are included in the report as Annexure XVII.

Singh’s actions were not in accordance with the Railways’ declared intention to improvise the quality of the rail. The Railways tried to pinpoint the reason for increasing instances of cracks on rails and decided in 1996 that permissible limits of hydrogen content in steel used for making the rail should be brought down.

By 1997, when Singh was giving relaxations, the issue of bad rail had become a matter of concern to the Railways. In February 1997 and again in April the then Railway Board chairman had written to the Ministry of Steel about the issue. Along with his letter (D.O No Track/21/96/0510/7 New Delhi dated 28.04.97) even a list of six railway accidents in two years—1995 and ’96—which were caused by ‘‘defective rails’’ was attached.

As per IRS-T-12/88 (Indian Railway Standards-Track, 1988) specifications the permissible limit of hydrogen was six particles per million (ppm). As per the revised standards of 1996, (IRS-T-12/96) it was brought down to three ppm. Higher presence of hydrogen had already been identified as a major cause of rail cracks. However, Singh continued to purchase rail with hydrogen content, in some cases as high as six ppm, through 1997, documents show. The purchase was stopped only after the Khanna accident.

The accident happened when the Golden Temple Mail, on its way to Amristar, derailed—the commission says because of a crack formed on the track—and some coaches fell onto the down track on which the Sealdah Express was speeding in the opposite direction. Sealdah Express rammed into the derailed bogies killing 210 and injuring several in both the trains. On 8-03-1999, Justice G C Garg of the HC of Punjab and Haryana was appointed to look into the cause of the accident.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05