To catch a mafia don

The Indian government deludes itself by thinking it will be easy to extradite Abu Salem from Portugal. The process could take several years....

The Indian government deludes itself by thinking it will be easy to extradite Abu Salem from Portugal. The process could take several years. This is because western democracies have such a poor opinion of India’s justice system that they disbelieve the evidence it presents.

Take the case of music composer Nadeem Saifee who was accused of plotting music magnate Gulshan Kumar’s 1997 murder. India requested Nadeem’s extradition from the UK but a London High Court rejected the petition saying that he had been falsely implicated.

Not just that, when India went in appeal to the House of Lords, that august body not only upheld the High Court’s verdict but awarded Nadeem 920,083 pounds sterling (Rs 6.25 crore) in legal damages. The London High Court’s verdict was indirectly vindicated this April when a Mumbai magistrate acquitted 18 out of 19 men accused in the case.

All this will go against India when it seeks Salem’s extradition, particularly if he’s cited as a co-conspirator in Gulshan Kumar’s murder. Two other factors will also favour Salem’s legal fight against his extradition.

One, since Portugal doesn’t have the death penalty like the rest of the EU, Lisbon will balk at extraditing Salem because the crimes he’ll be charged with can result in his execution.

The second factor favouring Salem is his religion. He can cite the almost genocidal Gujarat riots to successfully argue that he won’t get a fair trial in India. Karamjit Singh Chahal, a Khalistani separatist, managed to do just this in England ten years ago.

Salem’s extradition will be a complex business. When Indian CBI officers present evidence to a Portuguese court, the evidence will be assessed according to Portuguese laws. And the evidence will be dismissed if the judges think it is concocted. Western democracies see extradition matters as a matter of human rights. Which is why India’s extradition treaties with the US and Britain carry a political exemption clause that bars a person’s extradition on two grounds.

One, if he is accused or convicted of an offence of a political nature. Two, if he wouldn’t get a fair trial in his country on account of his race, religion, nationality, or political opinions.

Three Sikh assassins of General A.S. Vaidya used the political-persecution argument to delay their extradition from the US. They had been arrested by the US police in May 1987, and after India requested their extradition, a magistrate ordered their return. However, their case was re-heard and the final extradition came in November 1988, 18 months after their arrest.

Extradition matters are always tricky. A Pakistan businessman, Mohammad Lodhi, in England was wanted by the UAE for manufacturing Mandrax tablets in that country. But no British court would extradite him because UAE’s Islamic punishments of flogging, amputation, and execution violate the European Convention on Human Rights which Britain has signed.

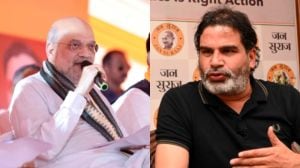

In a judgement two years ago, the Canadian Supreme Court has forbidden extradition to the US in cases where capital punishment was possible. In this case, L.K. Advani has sensibly declared that India would waive the death penalty if Salem is brought to trial. But it will take Portuguese courts at least two or three years to decide on the matter.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05