The ‘fairer’ sex whose whistles shattered the glass ceiling

Maybe this is what happens when you let women into upper management. They turn out like Cynthia Cooper. Or Coleen Rowley. Or Sherron Watkins...

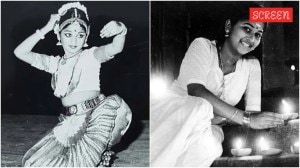

Maybe this is what happens when you let women into upper management. They turn out like Cynthia Cooper. Or Coleen Rowley. Or Sherron Watkins. Whistle-blowers, the lot of them. All three women took extraordinary personal risks to warn about misfeasance, incompetence and dysfunction within their organisations. Latter-day Cassandras, you might say.

Rowley, Watkins and Cooper were principal players in exposing the year’s biggest scandals. Watkins wrote the memo to her boss, Enron Corp CEO Kenneth Lay, that warned him about the energy company’s questionable management and accounting practices. Rowley is the FBI lawyer who detailed missteps and missed opportunities in the bureau’s pre-September 11 investigations. Cooper, an internal auditor at WorldCom, first raised questions about the company’s books, which led WorldCom to admit that its accounts were misstated by $3.9 billion. A trend or merely freakish coincidence? Are women the fairer sex when it comes to wrongdoing in high places? Do the actions of Cooper—not to mention Anita Hill and Erin Brockovich—suggest that it takes a woman to hang out the dirty laundry?

Let’s not begin to suggest that women possess inherently superior virtue. But let’s appreciate a couple of historical facts that may make a woman more likely to yank the alarm than a man. After years of tortured progress, women sit closer than ever to the inner circle of American corporations and government institutions. Close to it, but not in it. While the International Labour Organisation estimated in 1998 that American women held about 43% of all managerial positions, a survey two years earlier of Fortune 500 companies indicated women held only 2.4% of top management jobs and made up 1.9% of highest-paid officers and directors.

|

Coleen Rowley. Sherron Watkins. Cynthia Cooper. All three whistle-blowers took extraordinary personal risks to warn about dysfunction within their organisations. Are women then the fairer sex when it comes to wrongdoing in high places? Does it take a woman to hang out the dirty laundry? |

So, a few women have gotten close to the summit but generally aren’t themselves at the top. This makes women insiders, but insiders with ‘‘outsider values,’’ suggested Anita Hill, in a commentary for the New York Times last month. Hill—who challenged Clarence Thomas’ nomination to the Supreme Court in 1991 by raising sexual harassment charges—reasoned that the long history of employment discrimination against women makes them more sensitive to the defects of their workplace and more willing to do something about it.

Indeed, in explaining Watkins’s decision to blow the whistle on Enron, her friend and fellow Enron employee Jessica Uhl observed: ‘‘Look at (Enron’s) management team: There’s not a lot of female faces up there, and there never has been. Sherron’s a vice president, so she’s obviously not an outsider, but there is a dividing line. If you’re not part of the boys’ club, maybe that makes it easier to take a big risk.’’

In studies of gender and moral reasoning, female managers tend to demonstrate more ethical behaviour than men. The key word here is ‘‘tend.’’ Like much research, the results are often contradictory. A lot depends on how the study is designed. For example, University of Texas professor Robin Radtke has asked male and female accountants to respond to 16 ‘‘ethically sensitive’’ situations, such as trading stock on inside information. Overall, Radtke found no significant differences between the genders. But men and women did respond differently in specific situations, suggesting that the context of the dilemma—rather than gender generally—plays the most important role. On average, girls tend to prefer cooperative playground games, such as jumping rope, whereas boys choose competitive contests that produce clear winners and losers. ‘‘Girls want to be liked. They want a win-win situation,’’ says Helen Fisher, an anthropology professor at Rutgers University. ‘‘If one starts to cry, they’ll stop the game. Boys cast themselves in a hierarchy, and fight to be top dog.’’

Fisher, author of The First Sex: The Natural Talents of Women and How They Are Changing the World, says this behaviour dates to prehistory. ‘‘Women have always needed social connections to help them raise children,’’ she says. ‘‘While the men were out hunting an antelope, the women had to rely on one another to do the hardest job in the world, which is caring for a baby.’’ The obvious analogy to the business world is the varying management styles of male and female executives. ‘‘Women aren’t as sensitive as men to status in the workplace,’’ she says. They tend to take a broader view on issues, soliciting more opinions than a male colleague.

Does all this suggest that a woman, rather than a man, might be more likely to blow the whistle? ‘‘I think there’s something to it,’’ says Fisher. ‘‘When you’re not as committed to the hierarchy, you can see the ramifications a little better.’’

Perhaps it’s more than a coincidence that the first brand-name whistle-blower was a woman. In Greek mythology, Cassandra had the gift of foresight. She correctly predicted the outcome of many events, warning the Trojans, for example, about accepting a wooden horse as a ‘‘gift’’ from their Greek opponents. When Cassandra spurned the god Apollo as a lover, Apollo retaliated by making anyone who heard her prophecies believe they were lies. It was men, for the most part, who disbelieved her, leading inevitably to tragedy. Maybe some things have changed.

(LA Times-Washington Post)

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05