Report speaks of strategic US ploy to scuttle Agni

WASHINGTON, January 9: The United States is trying to impose fresh export curbs on India that could delay, if not prevent, further developme...

WASHINGTON, January 9: The United States is trying to impose fresh export curbs on India that could delay, if not prevent, further development and deployment of the Agni missile, according to a report in the Journal of Commerce.

The commerce department plans to alter a critical legal definition that could slow down or stop export of a wide-range of high-tech equipment, it said.

If the effort succeeds, it can affect export of an entire range of items from computers to machine tools if they can be used for missile production, the journal noted.

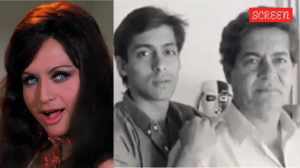

As part of this effort, the US Government helped in convicting two top executives of Fiber Materials Inc of Biddeford, Maine, in 1995 on charges of selling missile manufacturing equipment to India. The executives – Walter Lechman and Maurice H Subilia Jr – were, however, never sentenced.

The journal said high-tech exporters fear the plan to change definition of the term "specially designed" was aimed at making criminal conviction stick against them.

The Commerce Department, however, clarified that its attempt to redefine the term was only to meet the unspecified "export control objectives of the regulations while increasing the utility of the regulations to the public."

Sources suggest other agencies may be pushing the Commerce Department towards a tough interpretation for security reasons, the paper said, adding the Agni missile is considered to be one of South Asia’s biggest threats to stability.

A two-stage Agni was flight-tested in 1994, reaching a stage of over 600 miles. But according to a Pentagon report, the intended range is double that, making it capable of covering all of Pakistan and most of China.

"I believe," said Eric Hirschhorn, executive secretary of the Industry Coalition on Technology Transfer, "They (Commerce Department) should publish a definition of specially designed’. But I don’t know why they are pretending there isn’t one."

The main question is whether the control panel for the sophisticated press, exported by Lechman and Subilia to India, was "specially designed" for missile-making because it had the "effective capability to control" the process, as a Government witness claimed, or is the term supposed to mean the panel could be used only for producing missiles, and nothing else, as the industry defines the term.

The panel shipped in 1988 was part of a smaller machine, known as a hot isostatic press, which is capable of compressing materials evenly all around.

Larger presses can be used for making missile nozzles and nose cones, as well as parts for nuclear explosive devices, according to the Wisconsin university project on nuclear arms control.

The small press initially sold to India did not require a licence because it also has common industrial applications. However, after parts of a larger press were shipped from Switzerland to India in 1991, Leachman and Subilia were arrested for export rule violations.

The Government argued that the control panel for the small machine they had sold earlier could be used for the larger one, which would have needed a licence if shipped from the US.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05