Links in a Chain

BUMPING along Indian roads is a strange mixture of contrasting impressions. I enjoy the passing countryside whether it is verdant, wooded, p...

BUMPING along Indian roads is a strange mixture of contrasting impressions. I enjoy the passing countryside whether it is verdant, wooded, parched or pretty, I smile at glistening water bodies, frown at those that look drained out and shudder at the squelchy, smelly ones. I eagerly await the monuments and the temples, both important and obscure, while at the same time despair over their condition and then gag when we pass villages, towns and cities en route.

Most of these habitation, big and small are garbage dumps, choked with man, beast, building, and filth, devoid of that 8216;something special8217; quality and of any character, no matter how evocative the name of the place might be. Unforgettable is the image of a charpoy stuck into the stinking slush of a village thoroughfare that I once saw, where three men sat, greatly enjoying their tea and pakoras, undisturbed by dogs and piglets nudging their way towards the food.

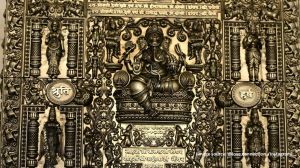

I have often wondered about us, our near blindness to filth and ugliness, our immunity to odours that almost make us faint. I am reminded of the words of Nandalal Bose, the great artist and thinker of Santiniketan, who said many decades ago that it is our 8216;8216;indifference to ugliness8217;8217; that is responsible for what we are. This naturally means that we are equally indifferent to beauty because if we had some discrimination then we would understand the link between beauty and cleanliness, for both arise from the same sensibility. 8216;8216;Loss of the sense of beauty8217;8217;, Nandalal Bose continues to say, 8216;8216;cuts off a large source of emotional uplift and enjoyment8217;8217;, and the reason why dirt and ugliness do not matter to us. Our indifference to beauty is one of the reasons that we enjoy spoiling and damaging our heritage, happily scratching wherever we can our names and proclamations of love, or just scratching for no purpose. Another reason is our near total unawareness of our past, the history that makes us, the events and people that date back to more than three thousand years. Till roughly the close of the eighteenth century, knowledge of the history of India existed in bits and pieces. All that was known was the invasion of Alexander the Great in 326 BC, and the happenings from the Islamic period onwards. William Jones, who had come to India as a Supreme Court judge in Calcutta, discovered a passion for Sanskrit and its rich literature, compared it with Latin and Greek, and realised that this perfect language opened up the gateways of ancient and sophisticated Indian civilisations that nobody previously knew existed with any precision or detail. Gradually the mapping of our history happened, helped immensely by the tracing of history after Alexander, the discovery of pillars, coins, rock cut temples and other marvels and the decoding of the many inscriptions that were found thereof. This is the way the knowledge deciphering of our history gradually came into being. In terms of time, it was not very long ago either, perhaps not long enough for awe, love and respect for our antiquity to sink into us, or to awaken in us the awareness of the beauty that our ancestors created.

It is also possible that our collective consciousness still responds to the history of non-history, believing in a sense that there is no history apart from what is convenient to us. We almost seem to be denying to ourselves that we are today, just links in a very long chain that will continue to grow after we are no more.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05