A brand new India

What does it say about India in the global imagination when in the sunset of his presidential life Bill Clinton smacks his lips and says h...

What does it say about India in the global imagination when in the sunset of his presidential life Bill Clinton smacks his lips and says his best meal ever was consumed in New Delhi? It will no doubt give yet another boost to orders for the presidential platter at the chosen restaurant, but it does indicate a curious new world when its most powerful man, for just a little bit longer, prefers to reflect on culinary memories of his subcontinental visit instead of strategic imperatives in a nuclear neighbourhood. Clearly India is no longer just the land of eternal nirvana, a breeding home for deadly stomach bugs. And if it has always been a source of icons — hippies on the road to Kathmandu, flowing-bearded gurus who promised glimpses of understanding to the Beatles and to pampered preppies, leprosy-stricken beggars in the City of Joy, interaction with whom was said to lead to cathartic experience, newlook maharajahs guaranteeing a long weekend of royal paradise in renovated palaces — the images today arequite different.

In a global village, with standardisation a corporate imperative, things Indian are now being claimed in attempts to stand out in a crowd, to add that little something to make a statement of style. From the preserve of alternative culture, things Indian are now being grabbed by the trendsetting mainstream. Survey the images of recent months. India was certainly the in-thing this summer when Liz Claiborne’s ad campaign was splashed with maharani pink sarongs with lush zari borders. Cherie Blair may have actively wooed her husband’s Indian constituency in Britain by clumsily donning Indian outfits, but India certainly got the designer edge when David Beckham proved his love for Victoria Adams — Posh Spice to the rest of us, she who makes up the other half of Britain’s favourite couple — by tatooing her name on his arm in Hindi. That was of course considerably less controversial than Madonna’s sudden penchant for Sanskrit shlokas and yogasnas in The Next Best Thing. And when Clinton reminiscedabout kali dal, not only did he finally banish memories of a dull Washington supper of McDonald’s burgers, he also differentiated the Indian meal from the strange curries sold in London and in Los Angeles.

The situation is, however, somewhat different in the near abroad. The anti-Hrithik Roshan frenzy in Nepal amply demonstrates this. For all the conspiracy theories, for all the denunciation of the media in relaying unsubstantiated quotes, for all the talk of local politicians manipulating protest for their petty ends, the episode resonates with a paranoia akin to the French fear of Hollywood. It may have taken just a misquote to elicit apprehensions about an Indian cultural invasion in the Himalayan kingdom, but calls to isolate the populace from Indian television — and presumed Indianisation — can be heard in most of the SAARC region. India’s terms of engagement with the rest of the world are, then, being slowly redefined. These are, after all, times when a heartily consumed platter plays a role in the lonely superpower’s newfound affection for this ancient land, when oldunderstandings with landlocked neighbours rest on the diplomatic skills of a light-eyed 26-year-old keen on just gyrating his way to superstardom.

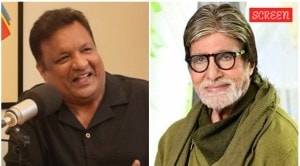

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05