Monuments are everywhere in Hampi. Some stand tall and elegant against the backdrop of giant granite boulders, others lie low and truncated. There are sculptures of elephants with missing trunks, court musicians with an amputated limb or nose – reminding the visitor of the devastation caused by a 16th century war to this once thriving metropolis that was at the centre of the Vijayanagara Empire. Then there are the other monuments – those that peek out from behind thick foliage and debris, waiting to be rescued through the exploration and conservation efforts that have been on since the 18th century.

Earlier this year, when the saalu mantapa, a pavilion at the Virupaksha temple in Hampi, collapsed in torrential rainfall, questions were raised about the alleged neglect of the World Heritage Site.

The conservation of Hampi is an exercise with few parallels, at least among India’s heritage sites. A variegated list of around 1,600 monuments, spread across an area of 250 square kilometres, makes Hampi one of the largest such sites in India to receive a UNESCO World Heritage tag. Apart from the monuments, there are about 30 villages and their people whose lives and livelihoods are intimately tied to the medieval ruins.

Though the entire area is regulated by the World Heritage tag — given to Hampi in 1986 — these 30 villages are spread across two separate districts, Vijayanagara and Koppal, and are governed by their respective administrations too. But it is the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) and the Karnataka government’s Department of Archaeology that has the painstaking task of keeping the monuments alive through a rigorous conservation process.

The spectacular city of Vijayanagara — or what we today know as Hampi — was the empire’s capital. (Credit: ASI)

The spectacular city of Vijayanagara — or what we today know as Hampi — was the empire’s capital. (Credit: ASI)

Despite these ground realities and multiple stakeholders, what makes Hampi fascinating is that the site is still being ‘discovered’, a process that has been on for decades. As archaeologists supervising the site would tell you, “a lot more remains to be known”.

The story of Hampi — and its rediscovery

Known to be the last great Hindu medieval kingdom, the Vijayanagara empire was established in 1336 by brothers Harihara-I and Bukka Raya-I of the Sangama dynasty. At its peak, the empire is known to have extended across almost all of southern India.

The spectacular city of Vijayanagara — or what we today know as Hampi — was the empire’s capital. Its magnificence was noted by several foreign travellers visiting the region, among them Portuguese Domingo Paes, who visited Vijayanagara in 1520 and wrote about the city that was “as large and beautiful as Rome”. The city, on the banks of the Tungabhadra, has also been the subject of numerous books, including Salman Rushdie’s latest Victory City, a fictionalised reinterpretation of the rise and fall of the Vijayanagara empire.

The glorious days of Vijayanagara, though, came to an end in 1565 when the combined armies of the Deccan Sultanates are said to have ransacked the capital after defeating Rama Raya, the de facto ruler of the empire then.

“It is said that the city burned for six months after the battle,” says Muhammad Ali, an ASI official at Hampi.

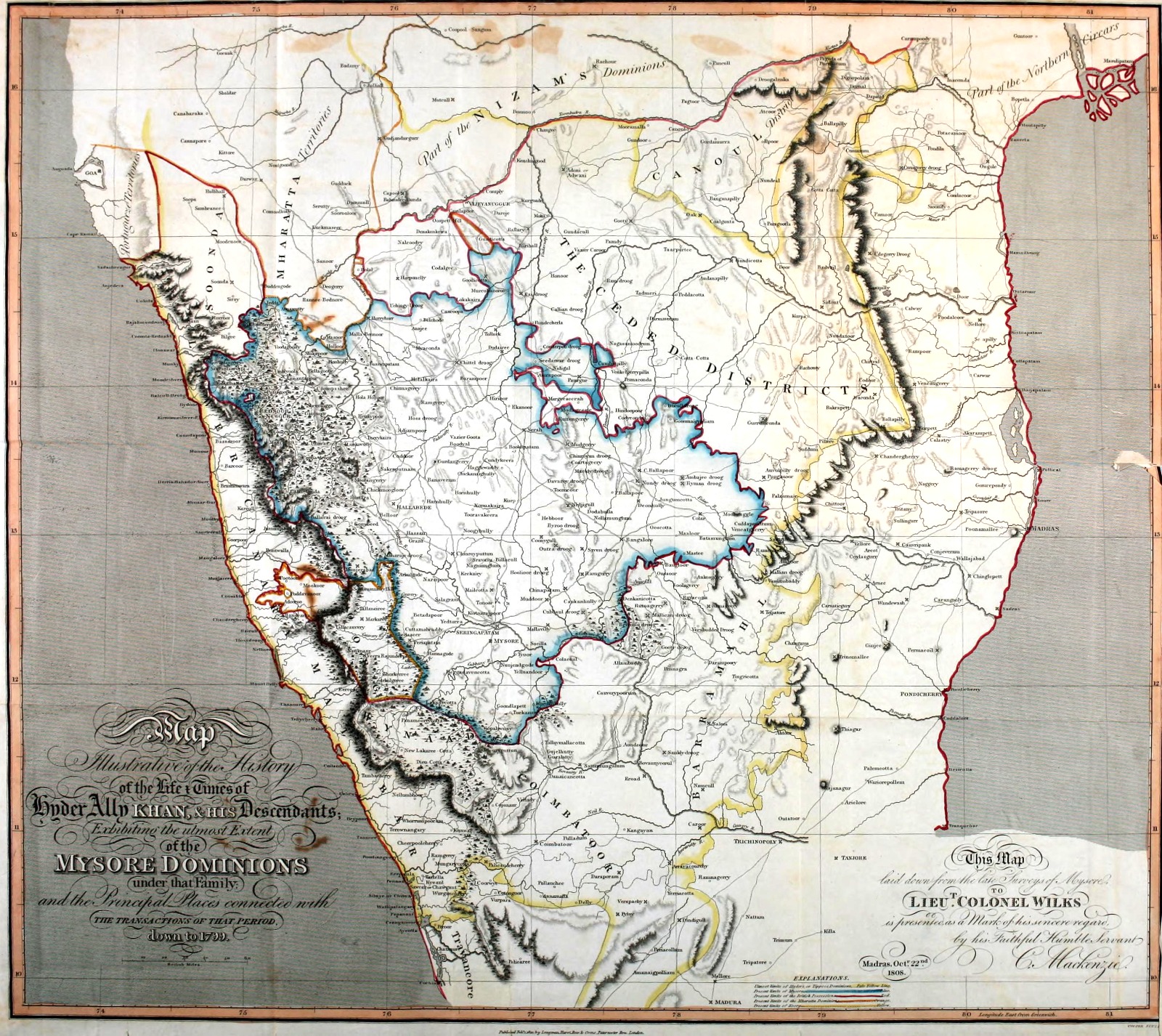

Although historians say that the nature and scale of destruction carried out at Hampi after the Battle of Talikota is debatable, everyone agrees that the site was practically untouched and largely forgotten till the end of the 18th century when the British first began exploring it. The British antiquarian Colin Mackenzie, who went on to become the first surveyor-general of India, made the first map of Hampi in 1799. He also produced a number of watercolour paintings of the monuments in the city.

Map by Colin Mackenzie. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Map by Colin Mackenzie. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In the years that followed, there was a steady increase in British explorers and photographers at Hampi. Among them was Alexander Greenlaw, who is known to have taken some of the earliest photographs of the Hampi ruins in the 1860s, much before any of the clearing or excavation work took place.

Apart from documenting the site, the British also engaged in some amount of early restoration. “For instance, in the Virupaksha temple’s gopuram, one can see a steel rod from 1856 with the mark ‘Made in England’ on it,” says ASI’s Ali. “It was put there by the British to support the gateway that would have otherwise crumbled.”

He points towards fragments of sculpted pillars that can be found sticking out from the ceiling tiles — examples of repair work, which, he says, was done by the British back in the 19th century.

It is only in the 1970s, though, that the first concentrated effort to excavate and conserve Hampi began under the directions of Saiyid Nurul Hasan, then Union minister of state of education, social welfare and culture. What followed was the Hampi National Project in 1976, which threw up some of the most extraordinary remnants of the 14th century metropolis that had hitherto been hidden under thick piles of debris and vegetation.

The site was practically untouched and largely forgotten till the end of the 18th century when the British first began exploring it. (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The site was practically untouched and largely forgotten till the end of the 18th century when the British first began exploring it. (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The white granite pavilions on either side of the street, stretching out from the Vitthala temple, for instance, were submerged under approximately 1.3 metres of debris, before they were excavated in the 1970s. Inscriptional evidence suggested that this was a flourishing marketplace for horse and elephant traders.

“Most of the core zone of Hampi — which includes all the administrative blocks, palaces and residential blocks of the ministers — came to light only after 1975,” explains Nikhil Das, ASI’s Hampi Circle Superintending Archaeologist.

Interestingly, it is only the granite base of these structures that survive today. Records suggest that the wooden structures they once supported were burned down in the course of the destruction of the empire.

George Michell, architectural historian and founder of the Deccan Heritage Foundation who spent more than two decades documenting Hampi since the early 1980s, says he was present when “much of the royal centre was dug out of earth”. The Pushkarini, the five-tiered stepped tank in the royal centre, was, however, not discovered when Michell first started documenting Hampi and therefore, does not feature in his first map of the city. It was sometime in the 1980s that the tank was dug out by the ASI.

The most recent addition to the excavations is the paan-supari bazaar, a kilometre-long market in front of the Hazara Rama temple, a portion of which was first excavated in 1985.

Das, the Superintending Archaeologist, resumed excavation of the market in 2022, following which another portion of the paan-supari bazaar was exposed. Das explains that inscriptional evidence suggests that this was the most lavish of the five bazaars of Hampi, attracting traders from across the world. Standing among the ruins of the paan-supari bazaar today, one can clearly see that much of it is still hidden under vegetation.

Despite the large-scale discoveries made at Hampi over the last few decades, experts believe the excavations at the site have been haphazard. Historian Vasundhara Filliozat, who has been studying Hampi since the 1960s, says that “instead of systematic excavation and documentation, the archaeologists were finding one place here and another there. So we still don’t have a proper idea about the whole city”.

It is only in the 1970s, though, that the first concentrated effort to excavate and conserve Hampi began under the directions of Saiyid Nurul Hasan, then Union minister of state of education, social welfare and culture. (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

It is only in the 1970s, though, that the first concentrated effort to excavate and conserve Hampi began under the directions of Saiyid Nurul Hasan, then Union minister of state of education, social welfare and culture. (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

ASI’s Das too agrees that the excavations at Hampi did not have a “problem-oriented approach”. “In Hampi, we would be excavating one thing and accidentally something else would be discovered and then we would go after that,” he says.

The ASI has, however, put excavations on hold for now. “We have concluded that wherever we dig in Hampi, we encounter something new,” says Das. “Since this site is so vast, we decided that it is better to first conserve what we have already found before digging any further,” he adds.

A fight to keep the ruins alive

An immediate impact of the 1986 World Heritage tag was that both the ASI and the State Department of Archaeology intensified their conservation efforts.

A part of the conservation was directed at repairing the destruction caused by the war centuries ago. The chariot at the centre of the Vitthala temple, for instance, shows remnants of a pair of horse sculptures that was in all probability destroyed. Ali informs that the ASI replaced the horses with two elephants plucked out from some other part of the monument.

Michell suggests that some of these efforts may have been misguided. “You cannot make Hampi new. All you can do is understand what happened and appreciate it,” he says. He points to an episode from the 1980s when the ASI attempted to restore a monolithic Narasimha sculpture that had been vandalised centuries ago, but it was left unfinished when the residents of Hampi protested against the original structure being tampered with.

But the conservationists had another, bigger, challenge on their hands — how to deal with Hampi’s living heritage, its people whose lives were tied to the land.

With Hampi’s UNESCO tag bringing in tourists, the inhabitants of the 30 villages that constitute the heritage site saw opportunities for themselves. The economy and infrastructure of the region improved as visitors streamed into the site, bedazzled by the monuments. Last year, Hampi attracted more than 83,000 Indian tourists and over 20,000 foreigners. “At present, there are 175 tourist guides approved by the Department of Tourism in Hampi and about 300 autorickshaws that run in the World Heritage area,” says Das.

But in 1999, Hampi had a scare when UNESCO put the site on the ‘World Heritage in Danger List’. The whip had followed the Karnataka government’s attempt to construct a bridge across the Tungabhadra, a violation of UNESCO’s policies for a protected archaeological area. Consequently, the government halted work on the bridge and set up an overarching body, the Hampi World Heritage Area Management Authority (HWHAMA), tasked with providing an integrated solution to the protection of Hampi.

The presence of this body was to change Hampi’s nature.

In 2007, HWHAMA established a masterplan for Hampi as part of which the entire area was divided into three parts — a 40-sqkm core zone that has all the major monuments, a 90-sqkm buffer zone, and the remaining peripheral zone. Each of these zones were brought under specific regulations and laws regarding construction activities and use of commercial and residential properties.

“Immediately, everybody living and working in Hampi became illegal, because as a World Heritage site, Hampi’s status is of a group of monuments, not a cultural landscape. This approach has not been inclusive of communities living within the larger site,” says Shama Pawar, convenor of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, (INTACH), Hampi chapter.

Pawar cites the example of the Hampi market that stretched out in front of the Virupaksha temple, which, she says, “had its own living reality”. Historical evidence suggests that at the peak of the Vijayanagara empire, the market would be bustling with activity. People lived and sold temple products here, while some of the mantapas served as resthouses for the travellers.

In its modern avatar, too, the market was the throbbing heart of Hampi, its shops selling trinkets and souvenirs to tourists. However, with the HWHAMA rules coming into effect, the shops were declared illegal encroachments and in 2011, a stringent evacuation drive cleared the entire stretch of the people and their livelihoods.

R Shanmugan, 72, who has been in Hampi since 1958, says that in 1992, he extended his home in Hampi village, adjacent to the Virupaksha temple, to build a guesthouse for tourists. However, when the HWAHMA rules came into effect, his guesthouse was declared illegal. “They allowed us to live here, but declared all commercial activities to be illegal, including something as simple as selling coconut water. How do we live here without earning a living,” he asks.

Krishna Devaraya, a resident of Anegundi who claims to be a descendant of the 16th century monarch of the Vijayanagara empire, says the World Heritage tag has been both a blessing and a problem for Hampi. “It is because of the UNESCO tag that whatever is left till now is still intact. However, it has also affected our culture and traditions. The priests in the temples must be allowed to live there for daily worship and the markets in front of them must be kept alive with strict rules and regulations,” he argues.

Nongjai Mohd Ali Akram Shah, commissioner of HWHAMA, however, says that those who were moved out of the heritage site were eventually rehabilitated in villages away from the site. “People had occupied the pavilions and pillars at the temple site. They have now been given concrete homes and amenities as well as a separate site for commercial activities.”

INTACH’s Pawar believes that the conservation of Hampi needs to be more organic, one which involves active local engagement. “The collapse of a mantapa or a pillar can always be fixed. The bigger concerns are environmental degradation and the lack of consideration of community engagement in planning. Hampi needs better sanitation, green mobility plans and architectural guidelines. The pillars of Hampi are, after all, its people and this ancient and rich landscape they inhabit,” she states.

Walking along the once thriving bazaar in front of the Virupaksha temple on a warm afternoon, one cannot help but notice the silence that surrounds this once-vibrant metropolis that was at the heart of one of the greatest Indian empires. Scattered on both sides are the stones and pillars of the empty mantapas. The stringent conservation efforts have cleaned up the mediaeval ruins and the marketplace, making the stretch a perfect spectacle for the visitor to Hampi.

The monuments are everywhere in Hampi — except, they stand in their splendid isolation.