Vandana Kalra is an art critic and Deputy Associate Editor with The Indian Express. She has spent more than two decades chronicling arts, culture and everyday life, with modern and contemporary art at the heart of her practice. With a sustained engagement in the arts and a deep understanding of India’s cultural ecosystem, she is regarded as a distinctive and authoritative voice in contemporary art journalism in India. Vandana Kalra's career has unfolded in step with the shifting contours of India’s cultural landscape, from the rise of the Indian art market to the growing prominence of global biennales and fairs. Closely tracking its ebbs and surges, she reports from studios, galleries, museums and exhibition spaces and has covered major Indian and international art fairs, museum exhibitions and biennales, including the Venice Biennale, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Documenta, Islamic Arts Biennale. She has also been invited to cover landmark moments in modern Indian art, including SH Raza’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the opening of the MF Husain Museum in Doha, reflecting her long engagement with the legacies of India’s modern masters. Alongside her writing, she applies a keen editorial sensibility, shaping and editing art and cultural coverage into informed, cohesive narratives. Through incisive features, interviews and critical reviews, she brings clarity to complex artistic conversations, foregrounding questions of process, patronage, craft, identity and cultural memory. The Global Art Circuit: She provides extensive coverage of major events like the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Serendipity Arts Festival, and high-profile international auctions. Artist Spotlights: She writes in-depth features on modern masters (like M.F. Husain) and contemporary performance artists (like Marina Abramović). Art and Labor: A recurring theme in her writing is how art reflects the lives of the marginalized, including migrants, farmers, and labourers. Recent Notable Articles (Late 2025) Her recent portfolio is dominated by the coverage of the 2025 art season in India: 1. Kochi-Muziris Biennale & Serendipity Arts Festival "At Serendipity Arts Festival, a 'Shark Tank' of sorts for art and crafts startups" (Dec 20, 2025): On how a new incubator is helping artisans pitch products to investors. "Artist Birender Yadav's work gives voice to the migrant self" (Dec 17, 2025): A profile of an artist whose decade-long practice focuses on brick kiln workers. "At Kochi-Muziris Biennale, a farmer’s son from Patiala uses his art to draw attention to Delhi’s polluted air" (Dec 16, 2025). "Kochi Biennale showstopper Marina Abramović, a pioneer in performance art" (Dec 7, 2025): An interview with the world-renowned artist on the power of reinvention. 2. M.F. Husain & Modernism "Inside the new MF Husain Museum in Qatar" (Nov 29, 2025): A three-part series on the opening of Lawh Wa Qalam in Doha, exploring how a 2008 sketch became the architectural core of the museum. "Doha opens Lawh Wa Qalam: Celebrating the modernist's global legacy" (Nov 29, 2025). 3. Art Market & Records "Frida Kahlo sets record for the most expensive work by a female artist" (Nov 21, 2025): On Kahlo's canvas The Dream (The Bed) selling for $54.7 million. "All you need to know about Klimt’s canvas that is now the most expensive modern artwork" (Nov 19, 2025). "What’s special about a $12.1 million gold toilet?" (Nov 19, 2025): A quirky look at a flushable 18-karat gold artwork. 4. Art Education & History "Art as play: How process-driven activities are changing the way children learn art in India" (Nov 23, 2025). "A glimpse of Goa's layered history at Serendipity Arts Festival" (Dec 9, 2025): Exploring historical landmarks as venues for contemporary art. Signature Beats Vandana is known for her investigative approach to the art economy, having recently written about "Who funds the Kochi-Muziris Biennale?" (Dec 11, 2025), detailing the role of "Platinum Benefactors." She also explores the spiritual and geometric aspects of art, as seen in her retrospective on artist Akkitham Narayanan and the history of the Cholamandal Artists' Village (Nov 22, 2025). ... Read More

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

- Tags:

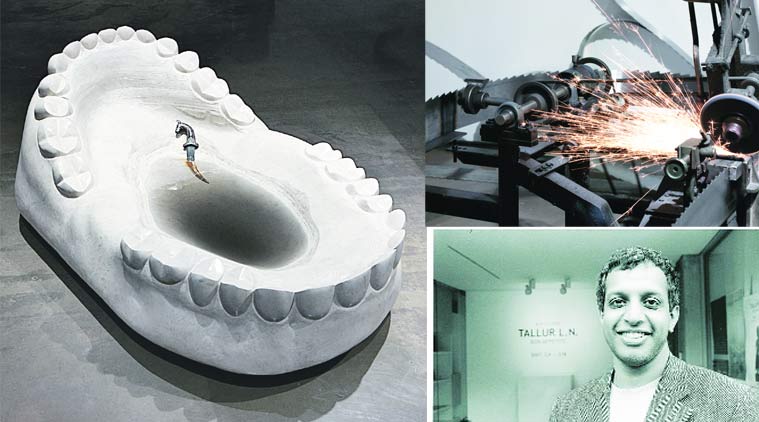

- LN Tallur

LN Tallur’s 2014 work Tongue Twisters; the artist; his 2015 work The Threshold

LN Tallur’s 2014 work Tongue Twisters; the artist; his 2015 work The Threshold