Home and Away

Making new friends in Pokhara and Kathmandu, and bonding over Bollywood and food.

Fewa lake at sunset with row of boats at the foreground in Pokhara , Nepal (Source: Thinkstock)

Fewa lake at sunset with row of boats at the foreground in Pokhara , Nepal (Source: Thinkstock)

I first saw Kathmandu late at night. With clear skies and deserted roads, the city opened up quietly. Skeletons of half-constructed structures jutted out in the distance, and modest homes stood next to dimly-lit, silent complexes and malls. Thamel, falling in the north of Kathmandu, popularly known as the “travellers’ ghetto”, was my destination for the night. The wide, potholed roads of the city converged into a narrow lane, opening up to congested shops, cafes, pubs and lodging homes, bearing a striking, resemblance to Delhi’s Paharganj. Thamel is also known for its famous live rock bars. And I found myself with a platter of momos and beer at a certain Reggae Bar, an unassuming but sprawling space that throbbed with Nepali rock music.

The gateway to Nepal’s tourism, Kathmandu is in the throes of urban development. The roads are partially demolished due to an expansion drive, and semi-constructed structures stand in every corner of Kathmandu city. A thick layer of dust hangs ominously in the air, leading local residents to wear pollution masks at all times. The spate of construction in the aftermath of the devastating 2015 earthquake has worsened the air.

Kathmandu’s cityscape is a curious mix — malls, shopping marts and night clubs stand alongside traditional architecture, which springs up in areas such as Patan and Bhaktapur. Against the hustle-bustle of the metropolis-in-the-making is a faint outline of Shivapuri, Phulchoki, Nagarjun and Chandragiri ranges.

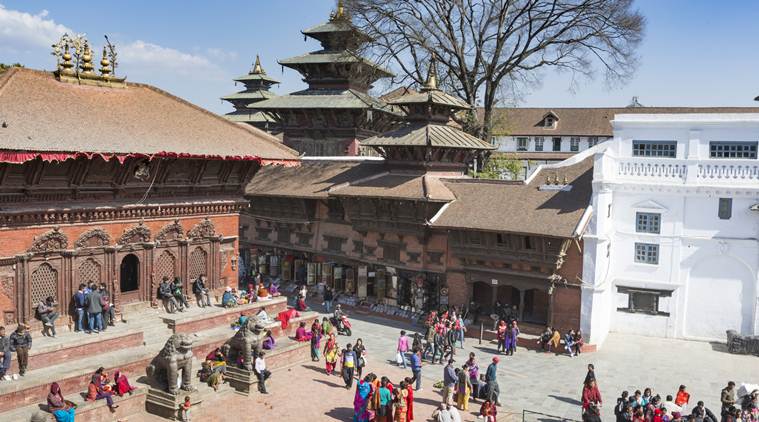

The fury of the earthquake is most evident at the Kathmandu Durbar Square. One of the three major Durbar Squares in the city, this cobbled plaza opens up amid a slew of temples, dating to the 12th century and after. Some of them are now held up by huge wooden beams. The Kasthamandap, a temple believed to be built from a single tree, lies in rubble. The Hanuman Dhoka Palace Complex, the Nepalese royal family residence until the 19th century, which is now a museum, is shut, its walls ripped apart by cracks, and held up with wooden beams.

Kathmandu’s Durbar Square after the earthquake

Kathmandu’s Durbar Square after the earthquake

Despite the destruction left behind, the square brims with an infectious energy. Dashain, the Nepalese version of Dusherra, will begin this week, and the people are not known to skip any form of revelry. In search of thakali thali, a Newari platter that serves simple but gratifying portions of dal-bhat-tharkari (lentils, rice and vegetables) with meat, ghee and sweet curd, I drove down to Midori Cafe in Baluwatar. The servings were delicious — the meat succulent, hot and divine, and the vegetables so fresh that they appeared to have been plucked from the kitchen garden a few hours ago. The people of this Hindu nation love their buff — in momos, spicy snacks and scrumptious steaks.

For an Indian, Nepal is reassuring and familiar. Transactions in Indian currency are common, and Bollywood is omnipresent — on radio, television and night clubs. An encounter with a group of young Nepalis at a cafe in Baluwatar made me realise they knew their Hindi movies much better. I found myself grappling for Hindi (sometimes, even Punjabi or Urdu) lyrics at an impromptu jam session.

From Kathmandu, my friends and I took a short detour to Pokhara, around 200 km west of Kathmandu and the second largest city of the country. It is the gateway to many trekking trails, such as the famous Annapurna base camp, Poon Hill trail and a few village hikes. The 25-minute flight dropped me to the Pokhara airport, a cantonment-like base which is the size of a hostel dormitory.

We chose to stay at the “lakeside”, the most commercial part of the town alongside Lake Phewa. I took off to explore on foot and cycle, and an occasional boat ride. It’s quite a sight: the pristine freshwater lake, dotted with colourful boats, and surrounded by lush green forested hills.

The famous Durbar square in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The famous Durbar square in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Expecting a quiet hill station, Pokhara surprised me with its energy — innumerable cafes, European bakeries and steakhouses crowd the street sides. More than the locals, I spotted travellers and backpackers.

One of the most popular activities in Pokhara, apart from paragliding and bungee jumping, is to trek to Sarangkot hills to watch the spectacular sunrise. At 4.30 am, however, we find the skies covered in a thick sheet of dark clouds. But we were fortunate to glimpse the stark white peaks of Dhaulagiri, Macchapuchhare and Annapurna II, standing out against the dreariness.

Much like Kathmandu, it is the nights in Pokhara that are interesting. Outlets such as Ozone and Busy Bee are packed with tourists and locals, mingling and dancing with each other to Bollywood, Nepali and Western beats. In the wee hours of the morning, on empty and unlit streets, it’s delightful to see late-night merrymakers walking (or swaying) back home. On one of my nights out, I strike up a conversation with a local, returning from the same club. “So you’re from India?” he says, “Nepal must be a welcome change.” Indeed, it is.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05