His left hand raised, trickles of bird droppings on his curled fist, Bhagat Singh is in good company – Subhas Chandra Bose in front and, diagonally across, Indira Gandhi. Singh died at 23, but the bronze statue of the boy revolutionary is of an older countenance, a hint of a worry line in between the famously arched eyebrows.

Built by Ram Sutar, the veteran of many a famous political statue, and installed on Independence Day in 2008, the sculpture stands on the lawns leading from the old Parliament building’s Gate No. 5, right outside the chamber where, nearly a century ago, Singh had carried out one of the most audacious attacks on the British colonial government.

On April 8, 1929, Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt, members of the radical Left group Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), had lobbed two low-intensity bombs in the Central Legislative Assembly, the precursor of today’s Lok Sabha or the Lower House of the legislature of British India. They also raised slogans of “Long Live Revolution” and “Down with Imperialism” and flung pamphlets that quoted French anarchist Auguste Vaillant to say, “It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear”.

Last week, as two men jumped from one of the visitors’ galleries in the new Parliament’s Lok Sabha and sprayed from gas canisters, there were echoes from that past – the six arrested in the case had, while saying their action was meant to draw the government’s attention to unemployment and the Manipur unrest, among other issues, invoked Bhagat Singh and called themselves members of his fan club.

Singh’s statue stands on the lawns of the old Parliament building. Chitral Khambhati

Singh’s statue stands on the lawns of the old Parliament building. Chitral Khambhati

Now, in the tense aftermath of last week’s incident, security officials at Parliament are on the edge, with visitor access being strictly monitored. The old Lok Sabha chamber, the scene of Bhagat Singh’s daringly subversive act that sent him to the gallows and to dizzying popularity thereafter, remains out of bounds behind tall doors and thick curtains.

Remarkably for someone whose active political years barely lasted a few years — of which he spent the last two in jail and some more in hiding – before he was executed by the British colonial government on March 23, 1931, Singh is among the most celebrated revolutionaries of the freedom movement. He straddles a rather polarised political landscape, courted by both the Left, Right and those in between, and finds resonance among anyone looking a cause, from farmers seeking MSP to unemployed youth, from those invoking him for his “courage” and “desh prem” to others who see in his remarkable erudition and breadth of ideas a “thinker” and a visionary”.

Almost every conversation on him — from students at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to academics and authors — veers into a dreamy hypothesis: “Aaj agar Bhagat Singh hote toh (if he had been around)…”

Almost every conversation on him — from students at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to academics and authors — veers into a dreamy hypothesis: “Aaj agar Bhagat Singh hote toh (if he had been around)…”

Almost every conversation on him — from students at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to academics and authors — veers into a dreamy hypothesis: “Aaj agar Bhagat Singh hote toh (if he had been around)…”

‘Medium height… small beard and moustache’

On the first floor of the Department of Delhi Archives in South Delhi is the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, a storehouse of archival wealth and once-proscribed literature on Bhagat Singh. The 1,700-odd books and documents are all donated by Dr Chaman Lal, former professor of Hindi translation at JNU and the man who has made it his life mission to collect every available piece of record on Bhagat Singh.

Somewhere in between the pages of these carefully archived documents and books stored in steels almirahs, Bhagat Singh comes alive. Born in 1907 in a Sikh family of landlords in Lyallpur in Faisalabad in present-day Pakistan, Singh was the second of nine children of Kishan Singh and Vidyawati. Inspired by his uncle Ajit Singh and father Kishan Singh, both Congressmen who played key roles in the nationalist movement, Singh was, by his teenage years, already a “well-known suspect” in police records.

A pillar inside JNU.

A pillar inside JNU.

In its report in 1926, the Criminal Intelligence Department describes him as someone of “medium height; thin oval face; fair complexion; slightly pock-pitted; aquiline nose; bright eyes; small beard and moustache”.

His Naujawan Bharat Sabha that he founded in March 1926 and the HSRA, an organisation that took its inspiration from socialist ideologies and movements in Russia and Ireland, unleashed a string of revolutionary action against the British. The most high-profile of these attacks was on December 17, 1928, when Singh and Rajguru gunned down police officer J P Saunders to avenge the death, a month earlier, of Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai after a police lathicharge on those protesting against the Simon Commission.

With the killing sending Singh and other members underground, the HSRA had limited means to publicise their cause. It was thus that the Assembly attack was devised – as a means to win broader public support in their fight against colonial rule.

In Without Fear: The Life & Trial of Bhagat Singh, the late journalist-author Kuldip Nayar writes that Singh and Dutt did a recce of the Assembly two days before the attack. “They wanted to ensure that the bombs they threw did not hurt anyone… A few minutes before the session began on April 8 at 11, (they) sneaked in unnoticed… An Indian member of the Assembly gave them passes at the entrance and disappeared,” Nayar wrote.

Letters that Bhagat Singh wrote in jail, displayed at the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre in New Delhi. (Photo credit: Uma Vishnu)

Letters that Bhagat Singh wrote in jail, displayed at the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre in New Delhi. (Photo credit: Uma Vishnu)

Then, just as (Assembly President) Vithalbhai Patel rose to give his ruling on whether or not the House should proceed with the discussion on the Public Safety Bill, a legislation that intended to curb the activities of socialists and communists, Singh and Dutt lobbed their bombs.

Singh and Dutt were arrested and the former’s link to the Saunders murder case established. At the end of a two-year trial in what came to be known as the Lahore Conspiracy Case, Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were sentenced to death.

In the handwritten letters that Singh wrote from jail – one from Lahore Central Jail asking his friend Jaidev to “arrange to send a fleet foot shoe…No. 9-10 will do”; a petition to the Punjab Governor asking to be “shot dead instead of hanged”; his moving last letter to his younger brother Kultar Singh, asking him to take care of his health and study well – are fleeting images of a man with a remarkable sagacity that’s way beyond his age. A few months before his execution, while in jail, Singh wrote his seminal essay, ‘Why I am an Atheist’, in response to his friends’ belief that there was a “certain amount of vanity that actuated” his disbelief.

In a powerful letter dated October 4, 1930, Singh writes to his father Kishan Singh, protesting against his move to seek clemency for him during the final stages of the trial. “I was astounded to learn that you had submitted a petition to the members of the Special Tribunal in connection with my defence. This intelligence proved to be too severe a blow to be borne with equanimity… I fear I might overlook the ordinary principle of etiquette and my language may become a little harsh while criticising or rather censoring this move on your part. Let me be candid. I feel as though I have been stabbed at the back. Had any other person done it, I would have considered it to be nothing short of treachery. But in your case, let me say that it has been a weakness — a weakness of the worst type,” he wrote in English.

According to Chaman Lal, whose latest book, The Bhagat Singh Reader, is a collection of the revolutionary’s writings, Singh wrote in English, Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi. He was also known to be “well-versed” in Sanskrit and Bengali and was learning Persian in jail.

A telegram dated March 18, 1931, on Bhagat Singh’s execution, displayed at the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre in New Delhi. (Photo credit: Uma Vishnu)

A telegram dated March 18, 1931, on Bhagat Singh’s execution, displayed at the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre in New Delhi. (Photo credit: Uma Vishnu)

Lal says that it’s this facet of Bhagat Singh that he has been working to highlight. “I have been trying to project the thinker-revolutionary side of him. Age has little to do with intellectual capacity. He was just 20-21 when he wrote and engaged with all these ideas. So far, only the courage part of his personality has been highlighted,” he says.

Prof S Irfan Habib, historian, whose works on Bhagat Singh, including To Make the Deaf Hear and Inquilab, are among the few mainstream academic works on the revolutionary, attributes Singh’s erudition to a practice he considers essential to scholarship – reading.

“Bhagat Singh read extensively. His mother Vidyavati would scold him because he would stuff his pant pockets with books and end up tearing them,” says Prof Habib, adding that it was his scholarship that set Bhagat Singh apart. “Why is it that everyone talks about Bhagat Singh, not Sukhdev and Rajguru so much? They were all equally courageous… What set Bhagat Singh apart were his ideas and thoughts”.

Jatindernath Sanyal, who was acquitted in the Lahore Conspiracy Case but arrested for Sardar Bhagat Singh, Singh’s first biography that was immediately proscribed, writes that while facing trial in the Special Magistrate’s Court, “Bhagat Singh began to read aloud to us the beautiful novel, Leonid Andrieve’s Seven That Were Hanged.” Sanyal lists books by Upton Sinclair, Eternal City by Hal Caine, “from which many speeches by Romily he had learnt by heart”, Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World, Ropshin’s What Never Happened, Mother by Maxim Gorky, The Career of a Nihilist by Stepniak, Oscar Wilde’s Vera Or, The Nihilists, and Kropotkin’s Memoirs of a Revolutionist, as among Singh’s “favourites”.

The man in the felt hat

From posters to comics, countless social media fan clubs to Bollywood films – from the Ajay Devgn-starrer The Legend of Bhagat Singh to Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s 2006 cult film Rang De Basanti — Singh’s life and dramatic end have steadily fed into popular culture.

Yet, has this man of ideas remained trapped in the iconography surrounding him? Deified in popular culture but on the margins of academic research?

In her book A Revolutionary History of Interwar India, Prof Kama Maclean, who teaches South Asian and World History at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and is History Chair at the South Asia Institute, University of Heidelberg, writes, “Bhagat Singh’s life has necessarily been the preserve of the popular since his death, because several levels of censorship have colluded to frustrate the documentation and retrieval of his story. The first among these was self-censorship. As a key member of several organizations labelled ‘seditious’ by the colonial government… Bhagat Singh’s actions and whereabouts in the years before his arrest were necessarily secretive.”

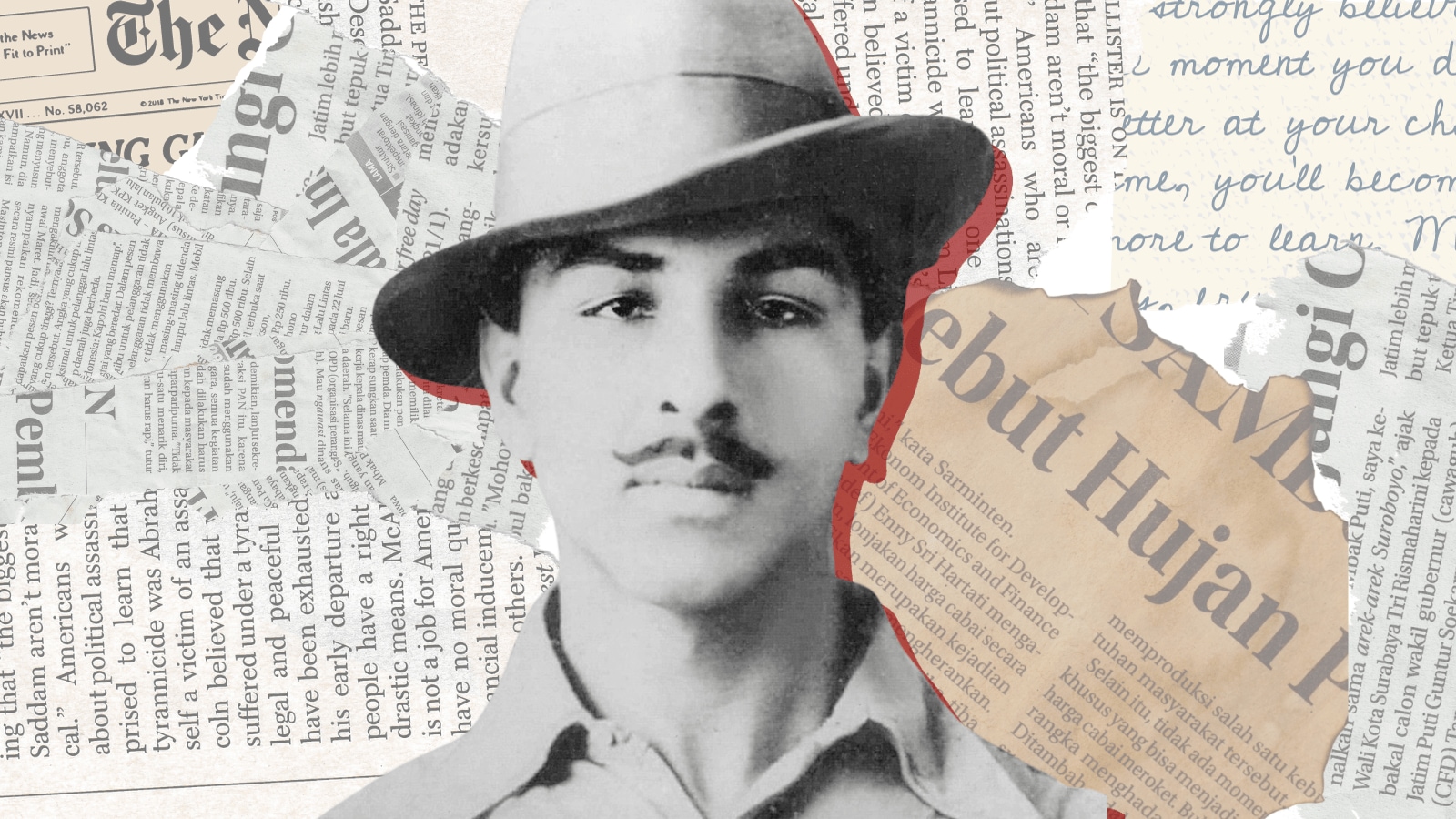

Chaman Lal says there are only four known photographs of Bhagat Singh — one taken around when he was 11, another at 17, then at 20, and the final when he was about 22 years old. (Express Photo)

Chaman Lal says there are only four known photographs of Bhagat Singh — one taken around when he was 11, another at 17, then at 20, and the final when he was about 22 years old. (Express Photo)

What then explains the surge in Singh’s popularity that started first with the 110-day hunger strike by Singh and his comrades demanding better conditions in Lahore jail and which reached dizzying levels following the secretly carried out execution of March 23, 1931?

Many point to an image of Singh that may have played its part – that of Bhagat Singh in a hat, the only photograph of the man in the initial days after his arrest.

On April 3, 1929, days before they carried out the Assembly attack, Singh and Dutt went to Ramnath Photographers, a studio in Old Delhi’s Kashmere Gate area, and posed for photos.

Despite the dangerous nature of his task and the near-certainty that the Saunders case would be traced back to him, a charge he knew would invite him the death penalty, the 21-year-old stares calmly into the camera. Experts now say the image, now a symbol of defiant nationalism, may have been part of a well-calculated plan — Singh and his HRSA comrades knew that the bomb attack would bring them and their cause national and global attention and the photographs would come in handy to illustrate related news events.

Maclean writes that it was Singh’s friend Jaidev Kapoor who arranged for the photo to be shot, with a specific instruction to photographer Ramnath: “Our friend is going away, so we want a really good photograph of him.”

Maclean further writes that while the initial plan was to collect the photographs before the bomb attack, the studio couldn’t get them ready on time. Worse, it turned out that Ramnath was also contracted to take photos for the police and had been called to the police station to take pictures of Singh and Dutt after their arrest on April 8, 1929.

Eventually, the revolutionaries collected the photographs, with Ramnath even handing over the negatives, possibly to avoid attracting police attention.

Maclean says the most striking feature of the photograph, apart from Singh’s expression, is his stylish felt hat. “We read into an image what we want to, or what we see. Different scholars have argued that it represents his love of western movies, it represents his taking up and mimicking of western style, that it represents a temporary disguise. His family members who met him before his death say he was like that to his death – an up-to-date young man. The hat, incidentally, he borrowed from a friend, and liked it so much, he never gave it back,” Maclean wrote in an email to The Indian Express.

In the Kashmere Gate area of Old Delhi, a search for Ramnath studio hit a dead-end. There was no trace of the photo studio that helped, as Jawaharlal Nehru would say in the days after Singh’s execution, the “mere chit of a boy leap to fame”.