Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

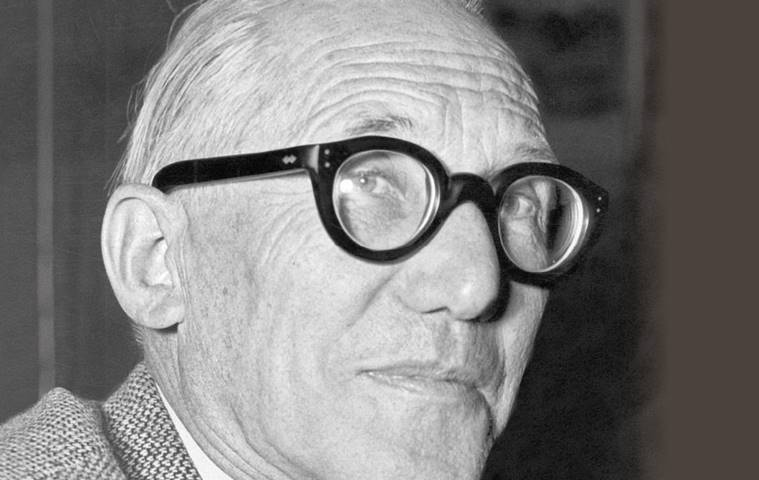

Le Corbusier, the man who designed Chandigarh, was a ‘fascist’, Hitler fan: New books

The row has divided experts with his supporters accusing the two writers of behaving “like tabloids — surfing on the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death’’.

Le Corbusier was the mind behind India’s first planned city

Le Corbusier was the mind behind India’s first planned city

For close to half a century, Chandigarh has been hailed as a marvel of modern architecture, but the man who designed it down to the doorknobs is now at the centre of a huge controversy over his alleged “fascist’’ links.

Le Corbusier, the mind behind India’s first planned city, was a “militant fascist” and his work was “inspired’’ by Nazi art, according to two new books published in France that have prompted calls for a reassessment of his legacy.

The claims in “Le Corbusier, un fascisme francais (Le Corbusier, a French fascism)” by journalist Xavier de Jarcy, and “Un Corbusier”, by François Chaslin, have shocked the European art world and cast a shadow over plans to commemorate his 50th death anniversary.

[related-post]

The Pompidou Art Centre in Paris, which is to organise a high-profile exhibition of Le Corbusier’s work to mark the event, is under pressure to highlight the newly-revealed “darker’’ side of his career. The books claim that Le Corbusier was an ardent admirer of Hitler and had close links with France’s war-time collaborationist Vichy regime under which he held several important posts. Among the serious allegations, threatening to undermine his legacy and reputation as one of the world’s most innovative architects, is that he was a member of a “militant fascist” group — France’s Revolutionary Fascist Party.

Rumours about Le Corbusier’s flirtation with the far right had swirled around for a while but this is the first time that his fascist past has been so comprehensively documented.

“Personally, I was very shocked, I found it hard to accept. You need time to absorb that kind of information,” Xavier de Jarcy told the BBC. François Chaslin told AFP that the architect “was active during 20 years in groups with a very clear (fascist) ideology” but that “has been kept hidden’’.

“When you hide something too much, one day it explodes,” he said.

The material in the two books comes mostly from Le Corbusier’s own personal correspondence and writings, which purportedly show that his sympathies for fascism were much stronger than previously thought.

Swiss-born Le Corbusier – his real name was Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris — moved to France when he was 20 and later became a French citizen. The Le Corbusier Foundation, which promotes his work, has not denied the claims and acknowledged that they are based on “thorough research’’. But it has questioned the timing of the revelations, alleging that they were meant to “manipulate’’ Le Corbusier’s death anniversary.

Le Corbusier’s Nazi links were not limited to his admiration for Hitler. He wrote articles in support of Nazis in two journals, “Plans” and “Prelude”, which he co-founded with Pierre Winter, head of the Revolutionary Fascist Party.

“He published around 20 articles which were clearly fascist in nature, where he declared himself in favour of a corporatist state on the model of Mussolini,’’ said Xavier de Jarcy.

In a widely quoted letter he wrote to his mother in 1940, Le Corbusier praised Hitler for his treatment of Jews and Freemasons and said, “Hitler can crown his life with a great work: the planned reorganisation of Europe”.

He also “courted” Mussolini with a view to selling him his vision of a utopian city, Ville Radieuse (The Radiant City), comprising high-rise apartments, a famous version of which he developed in south Marseille — Unité d’habitation.

It was an extension of his idea of pre-fabricated tower blocks which influenced France’s post-war housing planning for decades until it was abandoned in 1970s amid concerns that it was leading to urban ghettoisation and isolation of poorer communities.

He is also accused of “falsifying’’ his biography first to buy patronage from the Nazi puppet regime in France; and after the War to airbrush his Nazi links.

The row has divided experts with his supporters accusing the two writers of behaving “like tabloids — surfing on the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death’’.

Dr Caroline Levitt of Britain’s Courtauld Institute of Art said Le Corbusier had “ambiguous’’ politics.

“His politics tended to shift. He was more of an ideologist than a politician. He was interested in the potential of architecture – what it could do,” Dr Levitt said.

There is a view that his politics had “evolved’’ by the time he designed Chandigarh, but even that is disputed.