Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

The Big Picture: Passage through India

A journey is usually defined by the destination, or even by the route you take.

The scent of coal wafts in as you pass Kujong in Orissa, once Ground Zero of an agitation by farmers against the acquisition of their land for the Posco plant.

The scent of coal wafts in as you pass Kujong in Orissa, once Ground Zero of an agitation by farmers against the acquisition of their land for the Posco plant.

From a “spooky” path to a “smugglers” road, from apartment blocks to cock fights at local fairs, from Liquor Off Shop to Dutta Roy Mention, Ajay Shankar writes about snatches of life on his journey across Latitude 20°15.

(Photographs: Tashi Tobgyal)

A journey is usually defined by the destination, or even by the route you take. But this one, along Latitude 20°15’, cutting through four states across India’s waist, searching for people and signboards to understand Year 2015, fell into context even before it began.

Orissa’s Paradip coast, the starting point on the east, was still a few kilometres away, when four images slid past the taxi window on the right, all within a few seconds: a half-built shopping complex with a giant board advertising email, scanning services; an old woman in a small yard outside her shrub-fenced hut, wearing a torn, fading sari wound around her bare chest, trying hard to build a fire with a stick; a giant statue of Hanuman poised to leap; and then, a white Volkswagen Jetta slowly emerging unscathed from a massive hole on the “short cut” road.

As Jitubhai remarked eight days later, as he pressed the accelerator on the last kilometre of this journey on the western tip of Gujarat: “Wait, I am sure there’s more.”

Liquor Off Shop, Jaipur, the scent of coal…

The beach at Paradip

The beach at Paradip

{ December 22, 2014: Paradip to Cuttack, 84 km* }

It’s 5.30 pm, the sun is going down, and Tapan Das hunches over the taxi wheel, fighting off sleep after a “long trip” the previous day, squinting at a dimly lit stretch ahead. Das’s home in Paradip has fallen behind, Cuttack is still far ahead. Suddenly a well-lit sign flashes past: “Foreign Liquor Off Shop”. Liquor off? “Yes, that’s what they call outlets that sell alcohol in bottles,” he says. “Bars are called ‘On Shops’… We never pick up passengers from these places. They create a big nuisance.”

Suddenly, the headlights sweep past a milestone: Jaipur. Panic, where is he going? But then, the next one: Cuttack, 40. “Jaipur is just the name of a small place on this road,” Das warms up with a laugh.

Even in the fading light, after the dark sludge on the “city road” leading out of the port, it’s clear Paradip to Cuttack is a postcard in fast motion: paddy fields, a tributary of the Mahanadi on the right, brick kilns on its banks, and the scent of coal wafting in as you pass Kujong, once Ground Zero of an agitation by farmers against the acquisition of their land for the Posco plant.

It’s really dark now, and Das stops for a glass of “kadak chai”, determined to stay awake, hoping to return home to Paradip from the Cuttack railway station that night itself. “No, I won’t be picking up any passengers on the way back,” he says. Why? “It’s too dangerous. A driver I knew made that mistake once. There were four of them, and on a lonely stretch, a man behind threw a rope around his neck and tried to strangle him. But thankfully, he had the presence of mind to press the accelerator and ram the car into a barrier on the side of the road. Three of the four fled from the spot, one was injured and caught. My friend was injured too and the car got damaged — but at least he is alive now.”

A Chandila lookalike, Achanak Marg, the red flag…

The pond on Garhiya hill, next to Kanker, a small trading outpost

The pond on Garhiya hill, next to Kanker, a small trading outpost

{ December 23, 2014: Raipur to Kanker, 140 km* }

If you remember Ajit Chandila, the cricketer from the IPL scandal, you will know what Sandeep Rathi looks like — even down to those wraparound shades. To know more about him, the shiny gold bracelet on his wrist and this opening line should be enough: “I don’t usually drive these taxis, I’ve got employees to do that. Actually, I am into real estate.”

Raipur to Kanker, on the outside edge of Bastar in Chhattisgarh, begins with a blur of big city wanting to be a bigger city: blue signboards to the airport, the cricket stadium in New Raipur, some familiar destinations — Dantewada, Champaran — Mintu International School, and Yash Spoken English Class.

Rathi, meanwhile, has reached Bangkok. “I go there every two-three years. Do you know that they drive 160 kmph in Bangkok? Kya gaadi chalaate hain wahan ke log (How people drive their vehicles there)!”

Sensing an audience, Rathi now moves into top gear. “Have you ever heard about Achanak Marg — where anything can happen anytime in the night, all of a sudden? Nobody knows why, but it’s a road near the Bilsaspur side, where a number of unnatural deaths are said to occur. Is it spooked? I don’t know, but the dhabawallahs at the beginning of that stretch always warn drivers not to proceed in the night.”

Remind him about the other big Bilaspur story — the sterilisations that went wrong, killing 13 women this year — and he almost starts frothing at the mouth. After spitting out a bunch of expletives directed at everyone allegedly involved — the doctor, the medicine supplier, the politician — he sums it all up in one terse sentence. “Sab chor hain, saale (All of them are thieves, morons).”

The next topic? An alcohol-free state. “There are two Ms that people here can’t live without — murgi (chicken) and mahua (locally brewed liquor). And the government wants a daru-mukt Chhattisgarh,” fumes Rathi. As his anger rises, his command over English slips. “Tell me, how can you do that possible?” he asks.

With Rathi in full flow, the milestones whiz past unnoticed till the car gets stuck in an unfamiliar situation almost halfway through — a traffic jam. It’s Dhamtari town, big enough to boast of a jam, with college girls in tights hanging out at the main junction, sharing a laugh.

The effort to get free drains Rathi, and silence accompanies an empty stretch lined on both sides by what appears to be the outer edge of a forest. Then, everyone shakes awake. On the left, tied to a tree is a small, faded red flag. With a nervous laugh, Rathi says, “Bhailog ka area shuru ho gaya, bas mudke mat dekhna, chalte raho (The Maoists’ area has started, now don’t look back, keep going).” Silence, a few boards go by — Charama, Jhipatola — and finally a bright sight that brings a smile back on Rathi’s face. It’s the “famous Makri Dhaba”, a Punjabi welcome to Kanker, a small trading outpost surrounded by hills, with its Doodh river, Garhiya hill, and yes, this nameplate outside a house: Datta Roy Mention.

The raja, his daughter, a book on birds…

Kanker was in the midst of a local fair with cock fights, colourful beads and more colourful language

Kanker was in the midst of a local fair with cock fights, colourful beads and more colourful language

{ December 24, 2014: Kanker to Rajnandgaon, 146 km* }

The kick-off from Kanker, which is in the midst of a local fair with cock-fights, colourful beads and more colourful language, happens at an unlikely site — a palace. The Kanker Heritage Palace, as the property set in 1937 is now called, flaunts a sprawling compound that the two younger descendants of the local raja are trying to turn into a tourist destination, with four cottages on the lawns.

The USP here is that 37-year-old Suryapratap Deo, or simply and quite aptly “Jolly”, and his younger brother Ashwinipratap Deo personally take care of the guests. On their property, there are enough remnants of a distant past to capture anyone’s imagination — vintage vehicles, black and white photos, and a coat of arms. Yet, the takeaway image is that of a smiling Jolly carefully wrapping up a book on “Birds of India” as a gift for his five-year-old daughter who is happily playing outside with her pet dogs and a busy bunch of guinea fowls.

The drive to Rajnandgaon from where you can catch a bus to Nagpur en route to Khasgaon in Maharashtra, the next stop on Latitude 20°15’, takes you back in time — grass-thatched roofs, smoke curling up from a backyard — till two tribal women cut into the road on their bright blue Kinetic Honda. And, as you turn left from Kurud, driver Chiranjeevi’s “top-a-top road” from Balodh to Lohara is a 20-km surface comparable to some of the best in the country.

Gandhi caps, PegSheg, GJ…

Aurangabad to Nashik is a story in imagery: dark brown landscape, the first coconut trees and ponies grazing in the middle of nowhere

Aurangabad to Nashik is a story in imagery: dark brown landscape, the first coconut trees and ponies grazing in the middle of nowhere

{ December 26, 2014: Khasgaon to Nashik, 316 km* }

On the road from Khasgaon in drought-hit Jalna district, the final destination on the Gujarat coast still nearly 500 km away, the overpowering theme is white — pyjamas, kurtas, shirts, shoes, Gandhi caps, the pale sky, all white. And then, some brown from the dried cotton fields, and a dash of bright green jowar.

As you cross the unremarkable urban mess that is Jalna town, steel takes over, a seemingly endless stretch of factories. “You will hardly find any Maharashtrian doing the hard work here, it’s mostly people from Bihar,” says Krishna Rathore.

“If there are any Maharashtrians, you will find them doing managerial jobs or office work.”

Rathore, who stays in Jalna town, is your typical modern-day cabbie — a brash know-it-all, with an opinion on everything and anything. And, as he proceeds to give his take on how the world should be, the flat land rolls by without a break till this one large signboard promises relief: PegSheg.

But sensing the mood, Rathore says, a bit sternly, “20km to Aurangabad”. As soon as he speaks, a McDonald’s pops up, the first on

this journey.

Aurangabad to Nashik is a story in imagery: dark brown landscape; the first coconut trees; ponies grazing in the middle of nowhere; people sitting cross-legged on the edge of the road, vehicles whizzing past their noses; onions on a tractor in front; onion fields on the left, tiny green stalks reaching for the sun; and finally, vineyards escorting you all the way up to the outskirts of the city.

Then, under that giant flyover that takes you over Nashik to Mumbai, the first glimpse of the final destination — a car with GJ number plates.

No. 2 road, volleyball, the first helmet…

The road to Silvassa has loose gravel, giant holes and lorries pleading “Horn Amma Please”

The road to Silvassa has loose gravel, giant holes and lorries pleading “Horn Amma Please”

{ December 26, 2014: Nashik to Silvassa, 130 km* }

As his blue Indica takes you across the Godavari on the road to Peth and further to Silvassa in Dadra and Nagar Haveli — the overnight stop before the last haul — it’s clear that life is like a spy novel for Hemant Tahake.

Pointing to a Jain temple perched on a hill to the right, he says, “Sirf mandir jaa sakte hain, military area hai (You can only go to the temple, the rest is a military area).” Then, a while later, turning towards what appears to be a radar system on a hill, he says, “Pakistan ke saare plane idhar se track kar sakte hain (You can track all the planes of Pakistan from here).”

Finally, looking ahead at the road itself, Tahake adds with a knowing smile, “This is not the main road to Silvassa. Isko hum do numbri road bolte hain (We call this the No. 2 road). All the smuggling happens here — booze into Gujarat, and people from the coast into Maharashtra.”

But then, the tarred surface that he just spoke about simply disappears. Forget “new India”, this is all about “old India”: loose gravel and giant holes; women carrying pots of water on their heads; the back of a lorry pleading, “Horn Amma Please”; an old rusted pipeline, propped up by four brick pillars, piercing two hillocks; and, after another torturous bend, a gorgeous valley with a shimmering pond in the middle.

Soon, it’s Welcome To Gujarat, a different world. Well, not exactly because the checkpost guards ask you to switch off the camera while they take “something extra” from Tahake. But yes, NH848 in Gujarat is a world apart — smooth roads, trees on either side marked neatly in brown and white — and it’s almost as if you were passing through a typical military cantonment area.

Try hard, and you will actually find one fault. There are hardly any signs in Hindi or English. But that is quickly forgotten as you stop at Sudharpada to have the best tea of your life. “We are nearing Silvassa now,” says Tahake. He has “done this route” so many times before that he remains unmoved by the postcard huts silhouetted against the setting sun and the happy game of cricket that passes by.

A quick left turn before Vapi takes you to Silvassa on a small village road, hardly enough for two vehicles to pass through. You know you are in rural India when you see a game of volleyball about to start under a set of tubelights.

But it’s back to “new India” very soon, as the first fish stall appears on the main road in Kilvani, 12 km to Silvassa, followed by the first scooter helmet, and the first cement structure — what else, but a new block of apartments.

Mandal, Mandavi, Salve, Patel…

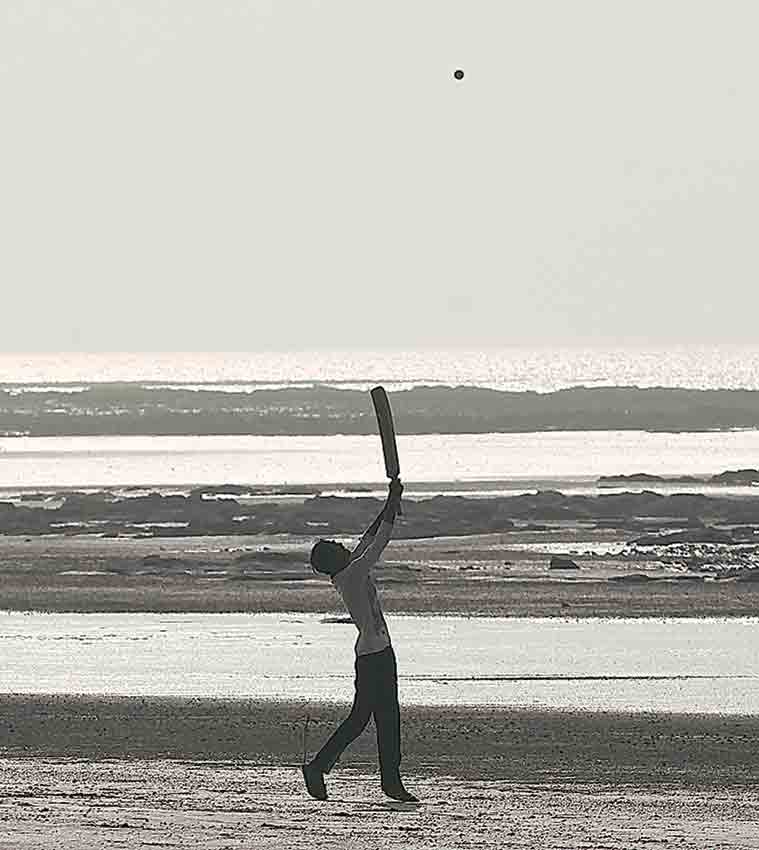

Children play cricket by the sea in Saronda village

Children play cricket by the sea in Saronda village

{ December 28, 2014: Silvassa to Saronda village, 37 km* }

Minutes after he has taken us across the border into Gujarat, about 30 km away from Saronda village in Valsad district, the last stop on Latitude 20°15’, the shy and polite Jitendra Patil sets the tone with this line, “Mere 12 jyotirling poore ho gaye (I have visited all the 12 temples with jyotirlings, the mark of Shiva).”

But just as you strap in for this spiritual journey, the real one appears to have come to an abrupt, anti-climatic end. At a T-point, a man washing his Nike shoes under a handpump, his gelled hair parted in the middle, jabs his voting finger downwards. “Saronda,” he says. So is this great journey going to end at a handpump?

“Wait, I am sure there’s more,” says Jitubhai. There is. The next turn takes us past an abandoned Parsi home to a well-laid out cricket pitch where a tournament sponsored by “Kishorebhai”, an advocate and local benefactor, is well into its final game. And there, smiling brightly, is the fourth unknown Indian on this nearly 2,000-km journey into Year 2015.

After Nitai Mandal, the lighthouse guard in Paradip, Ajay Mandavi, the arts and craft teacher in Kanker jail, and Sandhya Salve, the nurse in Khasgaon, it’s only appropriate that our fourth unknown Indian, Hardik Patel, a local cricket star who has high hopes from his engineering diploma this year, joins the journey along Latitude 20°15’ on its last kilometre. In about five minutes, Jitubhai presses down gently on the brake pedal, his car rolls to a stop on the sand, there are rocks ahead, the sea at low tide in the distance, another game of cricket on the brown sand. It’s over.

* Distance as measured on GPS.