Historian William Dalrymple at Idea Exchange: ‘Failure of Indian academics to reach out to general audiences has allowed the growth of WhatsApp history’

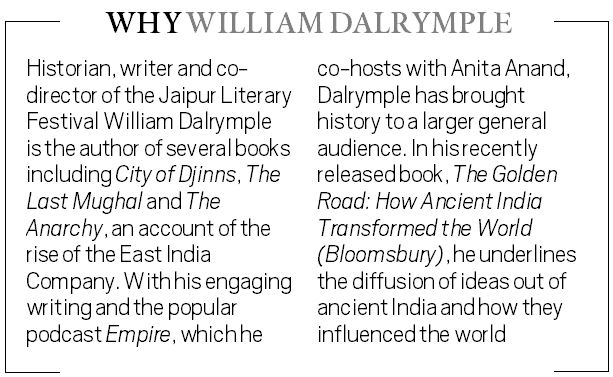

Historian, writer and co-director of the Jaipur Literary Festival, William Dalrymple is the author of several books including City of Djinns, The Last Mughal and The Anarchy, an account of the rise of the East India Company.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)Historian William Dalrymple on the transformative influence of ancient India, the myth of the Silk Route and why Indians write history books that are unpeopled. This session was moderated by Devyani Onial, National Features Editor.

Devyani Onial: Your new book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, is essentially about a sea route. Can you talk a bit about it?

The Golden Road is my own naming of a route that I think was far more important than the much-vaunted overland Silk Road. I don’t think many people realise that the Silk Road is not a term that was used in ancient or medieval sources. The first reference to a Silk Road, though disputed, certainly came into use in 1877 with the publication of a set of German geographical books by a man called Baron von Richthofen, who coined in German the phrase Die Seidenstrasse, which means the Silk Road.

The idea that there was a sort of superhighway connecting sea to sea across the thin waist of Asia is a myth. It’s a myth which obscures a real superhighway, which did exist, and which is becoming clearer and clearer in scholarship particularly over the last 20 years, following a series of excavations at Berenike, on the Red Sea coast of Egypt, and here in India at the Muziris excavations at Pattanam in Kerala.

Historian William Dalrymple (right) in conversation with Devyani Onial, National Features Editor. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple (right) in conversation with Devyani Onial, National Features Editor. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

So, the Golden Road is my answer to the Silk Road. It’s as much a made-up term as the Silk Road is, but it’s a counter-blast, which, for the classical period, is strongly rooted in evidence now of both archaeology and economic history. It also emphasises what we often forget, which is the amazingly enabling place that geography and meteorology have given India in terms of ancient trade.

… The Chinese have been very good at weaponising and mobilising this idea of the Silk Road, which is the basis for the Belt and Road Initiative.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Devyani Onial: So you think China has told their story better? What has stopped India from telling theirs?

There are two things which they’ve done. One is to project the story of their history in a way that has become very popular and accessible, and it is a naturally romantic story. But they’ve also been very good at using that idea, projected as an entirely peaceful global trade network in contrast to the militarised European networks of the 18th and 19th century, and building this whole extraordinary Belt and Road Initiative. There have been various talks of doing what has been called a Cotton Road, or a Spice Road, or more recently at the G20, IMEC (India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor), which then got shelved during the Gaza conflict. Why has India been slow to copy it? I don’t know, you’d have to ask the government.

Devyani Onial: While India hasn’t been able to tell their story to the world, do you think Indians tell it to each other a bit too enthusiastically, especially on WhatsApp? Whether it’s claiming that cosmetic surgery was available in ancient times or that the flying objects in the epics are evidence that there were planes and drones in ancient India?

My personal bugbear is that the study of history in academia entered a long phase from about the ’50s through to the beginning of the present century, where academics only talked to themselves, and often did so in deliberately obscure language of the Subaltern Studies Collective and so on… As a result, you’ve got the growth of ‘WhatsApp history’ and ‘WhatsApp University.’ It was the failure of Indian academics to reach out to general audiences.

It’s changing now but there’s been a 40- year vacuum for that, which has allowed ‘WhatsApp history’, plastic surgery, Mahabharata atomic bombs, sky vehicles like helicopters in the Ramayana, and all the rest of it to proliferate…That comes from a frustration that everyone in this country and in the diaspora is aware that there’s a great civilisation here, but slightly foggy on the details because no one’s writing on them. This book is an attempt to provide a well-researched answer to that question, what was it that India gave the world? What was it that came out of India and influenced the world around it?

Rakesh Sinha: You mentioned scholarly silence. Are you suggesting the Golden Road story was deliberately masked up?

No, I’m not suggesting that for a minute. It was studied in different academic silos so it was never pulled together into a single story. There’s a lot of detailed scholarly work being done, and there are, in Delhi, great scholars who’ve pulled lots of it. But there was a long period when I think that sort of thing was not happening.

Shalini Langer: How did you come up with the whole idea for your podcast Empire and why do you think that it’s become so popular? Second, your podcast almost regularly brings up the fact that colonial history is not taught in English and French textbooks. So, what is the awareness of colonial history among the general public?

As a historian, you’re very lucky if 100,000, maybe 200,000 people will read your books in five years. Empire is by no means the biggest in the world. We are number two or three in Britain. And yet, in two years, we’re reaching audiences now of 880,000 downloads a week. About colonial history, yes, that’s absolutely true. The British are taught a very insular curriculum but that’s changing now.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Uma Vishnu: Given the subject of the book, I’m sure you have faced accusations of furthering the Hindutva agenda. Was that a concern when you were writing the book?

There is this weird prejudice in this country that anyone who writes about Mughal history is a Marxist, and anyone who writes about ancient India is a member of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) . I’m neither. It is possible to be interested in Mughals without being a Marxist, and it is possible to be interested in ancient Indian history without being a member of the RSS, and to try and study both relatively objectively and factually. This is not a book of Indian history. This is a book of the diffusion of Indian ideas out of India. Obviously, the single most successful Indian idea in the early period was Buddhism. It got as far as Siberia and Mongolia, and most other countries in between. One-third of the book is about Buddhism. There is an extraordinary story to be told about the spread of Sanskritic and Hindu culture to Southeast Asia. We shouldn’t be ashamed or surprised or feel the need to press the mute button simply because it’s something which appeals to the far Right.

Rinku Ghosh: You have highlighted the cross-fertilisation of ideas, courtesy the Buddhist monastic universities and the exchanges they encouraged among Chinese and other Southeast Asian travellers. Unfortunately, while we talk about the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagara as a seat of a global confluence of cultures, Buddhist history has been glossed over in popular narrative. Yet China has weaponised that as a tool of cultural diplomacy. How can we prevent this appropriation?

The problem is that the Right considers Buddhist and Hindu history as the same. Yet Buddhism is a very, very important part of the story. This month London had two major shows on the Silk Road. One was in the British Library about Dunhuang, called ‘A Silk Road Oasis’. And the other was at the British Museum called ‘Silk Roads’. Both excellent shows but both almost completely omit India from the narrative. I have always thought that this is the fault of Western scholars, but maybe it’s because this story is not being pushed from here…

Yet when you go to Bodh Gaya today, there’s not only a lovely statue of Xuanzang, the Chinese monk, there’s a whole Chinese-India peace thing happening. This is something that these two countries can talk about sensibly, because there was a great deal of a very amicable to-and-fro at this period.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Suanshu Khurana: In the process of writing the book, what were the challenges? Do you think that there has been a lack of human stories, which usually jump at us in your other works?

For a historian researching the 18th century, there is an almost embarrassing richness of sources. Compared to that, this is a very empty cupboard in terms of biographical detail and you’re dealing with archaeology, epigraphy, a lot of very rich art history, which has been one of the main pleasures for me studying this. Nonetheless, amidst this desert, there are odd characters that are well-recorded and have biographical accounts of them… In the end, I think I managed to cover together enough biographical material to make this a readable account.

Harish Damodaran: Were maritime engagements and seafaring looked down upon? Generally crossing the seas was not considered good in Hinduism. Is that one of the reasons Buddhism eventually got exported out?

There’s a great deal of scholarly debate about it. The fact that the Buddhists didn’t discourage sea travel, that allowed Buddhist traders to make an early start, but quite early on, you find Hindu traders joining them. So by the time you’ve got the Mekong, running down the middle of Cambodia, it seems to have been treated not as foreign territory, as part of, if you want to call, a greater India. It’s there in various Puranas and in the laws of Manu, this prohibition about crossing the seas, but large numbers of people seem to have gotten around it one way or another.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Pooja Pillai: You’ve spoken a lot about the Gaza conflict over the past year. Do you feel historians have a special duty to speak up at times like this?

One of my books, From The Holy Mountain, involved me spending five years in the Middle East, particularly working on the Middle Eastern Christian communities, and the Palestinian Christians were one of them. So yes, I feel that there’s huge ignorance, particularly in where I come from in Britain, but even more so, in America about who the Palestinians are, what the history of the region is, what was the makeup of the region before the 20th century. And yes, I do feel a huge responsibility to try and get a forgotten truth out there.

Aakash Joshi: In India, we get this sense sometimes from the outside of academic history or even popular history, that a lot of it is also determined by government policy—for example, what is studied, where research is directed. Do you think that is a problem, the over-determination of politics and government in the study of history?

I think it’s unavoidable, because I don’t know anywhere in the world where governments do not determine school curriculums. And so you do find in areas where you have conflicted history, like Gaza, there are places in the world like Israel-Palestine or in Sri Lanka or here, where you have competing accounts of history. And what’s taught in the schools in the West Bank is very different from what’s taught in the schools in Israel. And both are entirely partial. What’s taught in the schools of India is quite different from what’s taught in Pakistan. It is true, but I don’t know a way around it, because all governments will determine education.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Aakash Joshi: I don’t mean just in terms of the curriculum setting, let’s say right now, in the research as well. So, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is government-funded, it does great work, but it may have a political mandate from top. Our universities have not had that kind of funding or impulse towards doing, say, archaeological research, not just textual research.

I feel very strongly that the ASI is criminally underfunded. I went on a long trip around Eastern Turkey this summer and the hotels there are about 20, 30 years behind India but the museums are 20 or 30 years ahead. I think India has got to invest more in its past, if only for pragmatic reasons of being able to generate tourism.

Kaushik Das Gupta: How have Southeast Asian historians looked at these cultural exchanges in the region? You’ve talked a lot about the cultural exchanges in knowledge systems, but do we also see societal things like the caste system, the guild systems, do we also see such things in the Southeast?

In the ’30s and ’40s, there was a great rise of nationalist historians, most famously RC Majumdar, who depicted India’s relations with Southeast Asia in terms of ‘Hindu colonies’, and you’ve got a lot of writing about how superior India civilisation conquered inferior Southeast Asian civilisations by the sword. This, quite understandably, produced an enormous backlash in Southeast Asian studies, so that the word Indianisation became an anathema in Southeast Asian university departments, not least because it’s historical nonsense that these were actually conquests. In general, there’s been a pushback from Southeast Asia against the idea of a militant, greater India, and Indianisation has been an unfashionable idea for a long time because of the overstatement of this in the ’30s and ’40s. And there’s a lot of scholarly debates about how far….what spread was Indian. Because to take your second question, the Hinduism of Southeast Asia was significantly different. As Tagore beautifully put it, when he went to Angkor, “Everywhere I could see India, yet I could not recognise her.” And that’s the perfect answer to that question, that it is Indian, and yet it’s not quite Indian.

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Historian William Dalrymple. (Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

Sudhakar Jagdish: You discuss history very lucidly. How do you tell a story?

It is a uniquely Indian thing to write history books that are unpeopled, and I think this is definitely a legacy of the dominance of Marxist history at universities. Marxist history tends to concentrate on economic and unseen social forces which move history, and there is a strong objection to biographical history. But my view is that, you look around you today and, take for example the Prime Minister of this country, you may like him or you may not like him, but few would say that he’s had no influence on the way this country has gone. Clearly, Amit Shah and Modi have completely altered the face of this country, and so as a historian writing on this period, if I was to do so, they would be at the centre of my story. But Marxist historians in the past tend to even sneer at historians who suggest that individuals can change the course of the river of history.

Shiny Varghese: Christianity is seen as a Western religion, whereas, with St Thomas coming to India, isn’t it more of an Asian religion?

So now, thanks to the Berenike excavations, we have very clear evidence of Hindu gods being worshiped in Egypt and the Buddha being worshiped in Egypt. It makes it all the more probable that Judaism and Christianity and other Roman forms of spirituality reached the Indian coast from this period. You also have accounts by the Church — Father Eusebius writing in the 3rd century on Indian Christians coming to Alexandria and looking for priests, manuscripts and relics, implying that there’s an Indian Christian community at the time.

So there’s absolutely no question that religions were passing in both directions. We have no idea whether the actual historical St Thomas, if he was a historical character, went to Kerala. But Christianity clearly arrived there early, as did Judaism.