The impact of rising global crude prices, on consumers and government finances, has been much reported and analysed. Not as much written about, however, has been the effect of hardening international fertiliser rates — on farmers, the Centre’s subsidy outgo and manufacturers/sellers.

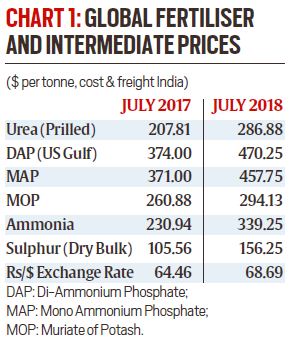

Two years ago, in July 2016, the average CFR (cost plus freight) price of urea imported into India ruled at a low of $ 198.31 per tonne. In July 2017, this rose marginally to $ 207.81 per tonne. But in July this year, it has gone up by 38 per cent to $ 286.88, even as the rupee’s exchange rate has weakened from an average of Rs 64.46 to Rs 68.69-to-the-dollar over the same period.

But it is not just urea.

It can be seen from Chart 1 that global prices of other fertilisers — mono and di-ammonium phosphate (MAP/DAP) and muriate of potash (MOP) — and key intermediates/raw materials such as ammonia and sulphur have also increased significantly in the last one year. The reason is oil itself: Ammonia, which is an input for both urea and MAP/DAP, is produced from natural gas. Sulphur — a raw material for phosphoric acid, which is used to make all phosphate fertilisers — is a by-product of refineries. Their prices, hence, move in tandem with that of oil and gas.

Story continues below this ad

The maximum retail price (MRP) of urea is controlled by the government. Since this is fixed at Rs 5,909.4 per tonne (for neem-coated urea, inclusive of 5 per cent GST or goods and services tax), fertiliser companies cannot pass on the higher international prices to farmers. This applies to both imported as well as domestically manufactured urea, despite the average “pooled price” of natural gas used for the latter now at Rs 737.8 per mmBtu (million metric Billion thermal units) on a gross calorific value basis, as against Rs 514.04 a year ago.

But for other decontrolled fertilisers, including DAP and MOP, the present MRPs are 18-20 per cent higher compared to last year. Even for complex fertilisers — containing varying proportions of nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium and sulphur nutrients — they are up by 10-15 per cent (see Chart 2).

In a scenario where retail prices of diesel used in tractors have also risen by over a fifth (from Rs 56.72 to Rs 68.50 per litre in Delhi), it represents a double blow for farmers. This, even as the Narendra Modi government has substantially hiked minimum support prices for crops in the current kharif season — pegging these at 1.5 times their estimated paid-out cultivation costs plus imputed value of unpaid family labour.

While farmers are paying the price, the industry, too, has taken a hit, more so on urea.

Story continues below this ad

“The specific energy consumption of an efficient plant is about 5.5 giga-calories per tonne of urea. At Rs 737.8/mmBtu — about Rs 812 (1.1 times) on a net calorific value basis — and 0.25 giga-calories for every one mmBtu, the feedstock cost alone is roughly Rs 17,850 per tonne of urea. Adding conversion costs of Rs 3,000-3,500 — towards wages/salaries, chemicals, consumables, repairs and maintenance, selling expenses, etc — takes the total to Rs 21,000-plus. The gap between this cost and the MRP of Rs 5,909.4 per tonne has to be met through government subsidy,” said a leading domestic maker of the nitrogenous fertiliser.

Till 2017, the Centre was releasing 95 per cent of the subsidy payment on urea and 90 per cent for decontrolled fertilisers on receipt of the company’s material at the railhead point or any approved godown of a district. But from January 1, this year, a new system of subsidy disbursal has been rolled out. Companies would be paid subsidy on any bag only after actual sale to a farmer and that transaction is registered at the point-of-sale (POS) machine with the retailer.

“Under the new system, the farmer’s identity will first be verified through Aadhaar-based biometric authentication. This is followed by the purchase done by him, along with his unique Aadhaar details, being captured by the POS device installed at the retailer’s end and connected with a central server belonging to the National Informatics Centre. In the event of the server being down (there have been repeated instances of that in the ongoing season), sales to farmers may continue, as they cannot obviously be asked to come back again. But the sales don’t get registered and our subsidy payments are affected,” the earlier-quoted manufacturer pointed out.

Related to this is the very nature of fertiliser sales. The bulk of DAP sales during kharif happens in May-June, while it is July-August for urea. Similarly, in the rabi season, sales of DAP are mostly from October to the first half of December, with urea from December to mid-February. “It means that while earlier we were getting subsidy payments round the year with despatch of material, in the new regime, these will be only in particular periods when actual sales to farmers happen. As a result, a lot of our money gets stuck and we incur additional working capital expenses. In urea alone, if I have to receive a subsidy of Rs 15,000 per tonne and it comes after six months, the interest cost, even at 8 per cent, for that period comes to Rs 600,” the manufacturer added.

Story continues below this ad

The problem may be less serious in non-urea fertilisers, where companies can hike MRPs — as they have already done. But there are limitations here as well, especially in an election year.

In DAP, for instance, the Centre is providing a fixed nutrient-based subsidy of Rs 10,402 per tonne for both domestic producers and importers. DAP from China is now being imported at about $ 430 per tonne CFR (lower than the $ 470 from the US), which translates into Rs 29,520 at current exchange rates. Adding 5 per cent customs duty and 5 per cent integrated GST on top takes the landed cost to Rs 32,550 per tonne or so. Inclusive of handling and other expenses, interest charges and dealer margins of Rs 4,000, the total works out to Rs 36,550. Netting out the subsidy, the importer can sell at Rs 26,150 per tonne, whereas most companies are now charging below Rs 26,000.

“We cannot really raise MRPs on DAP, MOP and complexes further, when national elections are due in eight months and there are crucial state polls before that. Nor is the government increasing the subsidy. On the contrary, thanks to the new post-sale disbursal system, it has so far spent just Rs 21,000 crore out of its budgeted subsidy outgo of

Rs 73,450.35 crore. That is, of course, only adding to our working capital woes,” an industry source noted.

In July this year, the average CFR (cost plus freight) price of urea imported into India stood at $ 286.88 per tonne. (Express photo by Gurmeet Singh)

In July this year, the average CFR (cost plus freight) price of urea imported into India stood at $ 286.88 per tonne. (Express photo by Gurmeet Singh)