Anonna Dutt is a Principal Correspondent who writes primarily on health at the Indian Express. She reports on myriad topics ranging from the growing burden of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension to the problems with pervasive infectious conditions. She reported on the government’s management of the Covid-19 pandemic and closely followed the vaccination programme. Her stories have resulted in the city government investing in high-end tests for the poor and acknowledging errors in their official reports. Dutt also takes a keen interest in the country’s space programme and has written on key missions like Chandrayaan 2 and 3, Aditya L1, and Gaganyaan. She was among the first batch of eleven media fellows with RBM Partnership to End Malaria. She was also selected to participate in the short-term programme on early childhood reporting at Columbia University’s Dart Centre. Dutt has a Bachelor’s Degree from the Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Pune and a PG Diploma from the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai. She started her reporting career with the Hindustan Times. When not at work, she tries to appease the Duolingo owl with her French skills and sometimes takes to the dance floor. ... Read More

AI edge for TB therapy: A test to track your last dose, drones to deliver drugs at your doorstep

Know about top innovations that will be part of the national TB elimination programme, help in screening and treatment.

The screening net has been widened with different types of tests to detect TB infection in samples other than sputum, such as blood, saliva, or stool. (Source: File)

The screening net has been widened with different types of tests to detect TB infection in samples other than sputum, such as blood, saliva, or stool. (Source: File)A simple strip test can now track whether a patient has been taking their anti-tuberculosis (TB) medicines regularly. Another test can pick up the infection in blood, saliva and stool samples. Meanwhile, drones can deliver medicines to patients and even pick up their samples from hard-to-reach areas.

These are among the handful of innovations selected by national experts that may become a part of the country’s national programme on tuberculosis elimination. They would help in widespread screening as well as ensuring follow-ups for treatment.

Earlier this week, the experts went through demonstrations and data for 228 such innovations from across the globe, scored them depending on how close they are to use in humans, whether they are cost-effective, and if they can be implemented in India.

Why are innovations significant?

This comes even as India is working towards its goal of eliminating TB by 2025, five years ahead of the global target. “The idea behind the conference was to look for what we can do better. At the conference held last year, around 30 to 40 innovations from within India were demonstrated. Experts selected technologies like hand-held X-ray, low cost nucleic-acid amplification test (a type of RT-PCR test), and AI for reading the X-rays. These innovations have been utilised under the national programme now during the 100-day campaign. This year, we did a wider search and looked at innovations from across the world,” said Dr Rajiv Bahl, director-general of the Indian Council of Medical Research.

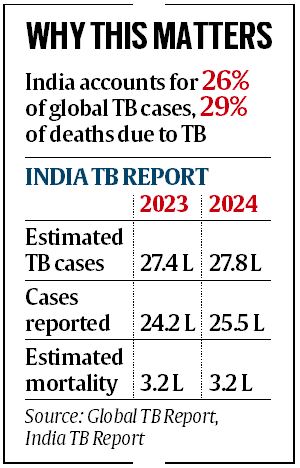

While India saw a decline in the estimated number of cases and deaths in 2023 — and an increase in the number of patients diagnosed, a positive sign that patients are not being missed out — it still remains far from its goal of eliminating TB by the end of this year. With 28 lakh estimated cases, India still accounted for global TB cases in 2023. And, with 3.15 lakh deaths, the country accounted for 29% of the global burden, according to the Global TB report 2024.

What are breakthroughs?

The use of artificial intelligence to read microscopy slides and X-rays for automated detection of tuberculosis is a huge relief in remote areas where there is a shortage of healthcare workers.

The screening net has been widened with different types of tests to detect TB infection in samples other than sputum, such as blood, saliva, or stool. These tests may look for antibodies in blood, or use PCR to detect the pathogen in other samples, or use another inexpensive way of amplifying the genetic material called LAMP. “In many patients, especially children with tuberculosis, it is very difficult to generate a sputum sample. These alternative tests can play a role in detecting TB in persons who are unable to give a sputum sample,” said Dr Bahl.

The dose-tracking tests are a breakthrough as one of the biggest challenges with TB is that people have to continue taking medicines for months even after they start feeling better — patients may have to take medicines for four months to two years depending on the type of TB they have. This leads to many patients dropping out in the middle of the treatment. “This makes the patients drug-resistant. Also, when health workers ask the patient whether they have taken the medicine, they may say yes even if they have not. These tests are a way to check compliance,” said Dr Bahl.

One of the tests selected by the experts was a strip-based test for the commonly used medicine Rifampicin. When a patient’s saliva is put on the strip, it can tell whether they have taken the medicine in the last 24-hours. There were tests that could check the levels of the medicines in the blood as well.

A programme in Telangana successfully demonstrated the use of drones over a long period of time in delivering medicines and carrying patient samples back to enable last-mile tracking.

However, it is the technology for detecting TB as well as drug resistance that would have a huge implication. This next generation sequencing test can tell whether a patient is resistant to any of the15 anti-tuberculosis medicines at one go. At present, a PCR test is used to check for resistance, and usually to only one of the commonly used medicines called Rifampicin. This next generation sequencing test would be able to detect several medicines, including the recently started BPaL regimen that uses four drugs to cut the treatment time of drug resistant TB to six months. “This test, however, is unlikely to be included in the national programme immediately because it costs around Rs 5,000 to 10,000 per patient, which is a little steep for a programme. However, it is likely to become cheaper in the future. If you look at RT-PCR tests, it used to cost anywhere between Rs 1,200 to 2,000 before the pandemic. Now, it can be done for as little as Rs 200,” said Dr Bahl.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05