In 1905, French editor Pierre Lafitte commissioned Maurice Leblanc to write a series of short stories for the Je sais tout magazine to rival the UK-based The Strand‘s Sherlock Holmes. In response, Leblanc gave birth to Arsene Lupin, a suave, genius thief and a master of disguise. The first story turned crime fiction on its head, beginning with the arrest of the perpetrator. It was an instant hit. Leblanc went on to publish a volume of work comprising 17 novels and 39 novellas.

More recently, Lupin reincarnated in Omar Sy’s eponymous 2021 French-language Netflix thriller. In the pilot episode, we are introduced to a Lupin-inspired Assane Diop (played by Sy), who orchestrates the theft of a priceless necklace, belonging to the erstwhile queen of France, Marie Antoinette, from the iconic Louvre Museum in Paris. And, as much of the internet has noted, life seemed to imitate art this Sunday, when similar scenes played out in real life at the museum.

In a daring daylight robbery, four masked thieves broke into the Louvre with the help of a truck-mounted crane, cut into the display glass, and slipped away with Napoleon jewels worth over $100 million. Authorities have ruled it a “commodity theft” as the assailants were not interested in stealing art, unlike the 1911 heist of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The thieves targeted jewels that could potentially be taken apart and sold separately.

Story continues below this ad

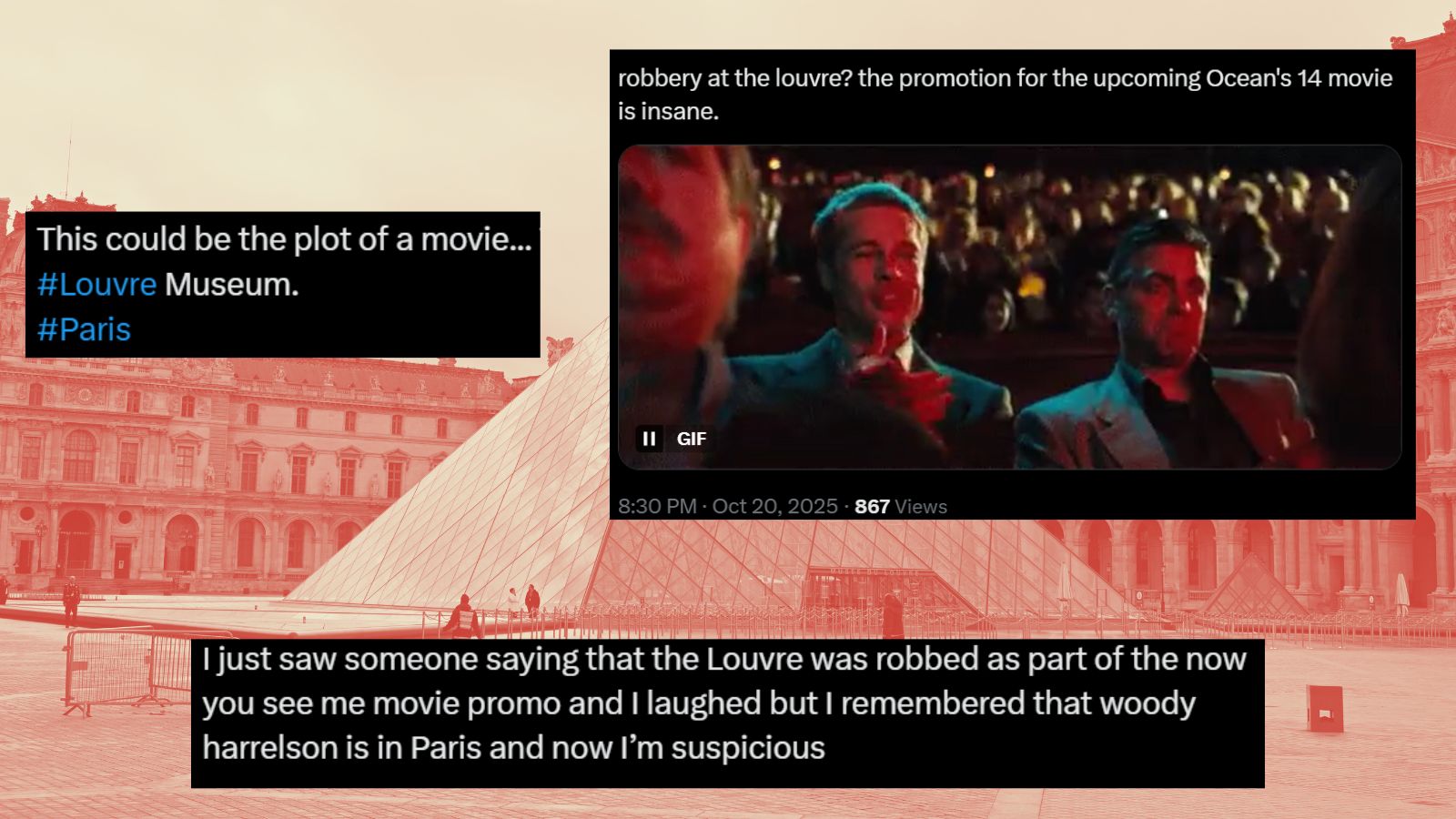

Predictably, the internet was obsessed. Conversations spotlighted the many serious issues, from staffing shortages to delays in security upgrades, that plague the Louvre. Another section drew parallels to a much-loved genre of cinema: heist films. Soon, lists of must-watch movies appeared on several platforms. Interest in Lupin and George Clooney-starrer Ocean’s Eleven saw a spike on Google Trends. Many said the seven-minute heist and the unusual getaway vehicles—the Yamaha TMax scooters—sounded like details right out of an action movie.

The Louvre robbery sparked a meme-fest on heist films.

The Louvre robbery sparked a meme-fest on heist films.But what is it about heist films that has audiences hooked?

The ‘slick’ hero

First and foremost, movies like the Ocean’s trilogy, Now You See Me, Italian Job, or Gone in 60 Seconds often have charming anti-heroes who can dazzle their victims and audience alike. As masters of disguises, they hoodwink even the viewer into believing their suavity, wit, and brilliance. When Ocean’s Eleven came out in 2001, a New York Times review called the cast a “who’s who of People magazine’s sexiest men alive”.

Indeed, the protagonists are not always as slick. You can have a crew of oddballs and misfits like Woody Allen’s Small Time Crooks or Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. But then there are the plot twists, the action, the chase, and the witty one-liners that can make up for the lack of charisma.

Story continues below this ad

Then there’s the appeal of being in on a “forbidden” act. Heist films often allow viewers to listen in on the plotting and witness the hoodwinking of authorities firsthand. The viewer always knows more than the investigators on the scene.

As Kirsten Moana Thompson writes in her 2007 book, Crime Films, such cinema can offer “escapism and voyeurism, or in other words the pleasure of watching stories about illicit worlds and transgressive individuals”. These “transgressive” behaviours may appeal to our “fantasies and desires”.

Rooting for the ‘bad guy’

Unlike most cinema, where good wins over evil, heist films have the audience rooting for the so-called villain. Audiences want the mastermind to walk away unharmed; they celebrate when an empathetic police officer lets them get away with it. In a paper titled “Rooting for the Bad Guy: Psychological Perspectives”, researchers suggest that this is due to the “attribution” and the “exposure effect”.

When viewers assess a person or character based on the limited information they have about the individual, it can lead to a “fundamental attribution error”. If you see someone doing something bad, you think this person is “bad”. But in heist films, we tend to have far more information about the “bad guy”, so we “shift from making snap judgements” to “assessments” from “situational knowledge”. In other words, our perception of someone changes when we learn about their circumstances. Similarly, since the “bad guys” have more screen time, hence, more “exposure”, viewers are more likely to view them favourably.

For instance, in Lupin, we excuse Diop’s felonies because we know he is motivated by a “higher goal”— avenging the death of his innocent father, who was falsely accused of a crime. In The Italian Job, we root for Mark Wahlberg, who is seeking revenge for the murder of his mentor, instead of Edward Norton, who double-crossed the team.

The anti-capitalist sentiment

Story continues below this ad

Most importantly, heist films find resonance in their inherently anti-capitalist nature. Often, the protagonist is an underdog, a poor nobody taking on a giant corporation or government. Or they are the Robin Hood-incarnate, much like Arsene Lupin, stealing from the rich for the poor. You see it play out in the Now You See Me franchise, where four illusionists steal from large corporations and expose unethical practices. Even in the Ocean’s movies, the Clooney-led crew is bound by somewhat of a moral code: They steal only from the ultra-rich, and mostly to “right a wrong”.

As Daryl Lee writes in his book The Heist Film: Stealing With Style, heist films can be a critique of the social order, where those marginalised by the mainstream society in some way come together to work against it. “At its most abstract, this represents a utopian impulse, or at least a bohemian one, to form an unconventional collective on the margins of society,” Lee states, adding that the genre “inscribes a wish-fulfillment for a new social order”.

At its core, the heist film indulges the innate human fascination with rebellion and transgression. In reality, such acts would provoke grief, outrage, and the full machinery of justice—as evidenced by the hundred-strong team now investigating the Louvre theft. Yet within the safe confines of cinema, we can momentarily yield to the whisper of that devil on our shoulder, delighting in the fantasy of defying the system and getting away with it.

The Louvre robbery sparked a meme-fest on heist films.

The Louvre robbery sparked a meme-fest on heist films.