US President Donald Trump has initiated trade wars so far primarily against three countries: China, Canada and Mexico.

On February 1, he ordered the imposition of a 25% additional tariff on all imports from Canada and Mexico, and a similar 10% levy on Chinese goods entering the US. On February 3, he announced a 30-day period pause on the implementation of the new tariffs on Canada and Mexico, even while retaining the 10% blanket additional duty on imports from China.

China has subsequently hit back through import taxes of 10-15% on select US imports – crude oil, liquefied natural gas, coal, farm machinery, pick-up trucks and large-engine cars.

But these tit-for-tat measures may not inflict much damage, as the targeted goods represented just about $23.6 billion worth of US exports to China in 2024. That’s small relative to the total US merchandise exports of $143.5 billion to China. The 10% Trump tariff, in contrast, covers the entire $438.9 billion value of Chinese goods imported into the US last year.

Vulnerability at the farm

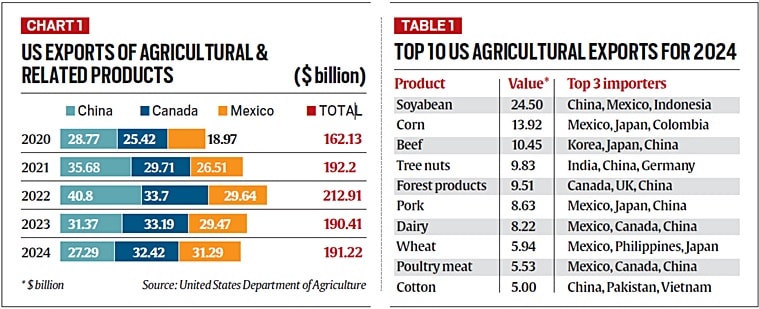

The real damage from Trump’s trade wars could come if the affected countries were to take retaliatory action targeting US exports of farm produce. These not only totalled $191.2 billion in 2024, but a big chunk of that interestingly went to the same three countries – China, Canada and Mexico – whose combined share was $91 billion or 47.6% (chart 1).

Take China, which is the largest buyer of US soyabean, cotton and coarse grains (excluding corn), besides being its No. 2 market for tree nuts (mainly almonds, pistachios and walnuts) and No. 3 for beef, pork, dairy, poultry meat and forest products.

Mexico is, likewise, the biggest destination for US corn (maize), wheat, pork, dairy and poultry meat products, while No. 2 for soyabean. Canada, too, is a major importer of American forest, dairy and poultry products (table 1), and even larger when it comes to fresh as well as processed fruits & vegetables; bakery goods, cereals & pasta; chocolate & cocoa products; confectionary, food preparations; ethanol; dog & cat food; and wine.

Story continues below this ad

To get an idea of what retaliation can mean, one needs to only consider the case of soyabean and corn. In 2024, China’s soyabean and Mexico’s corn imports from the US were valued at $12.8 billion and $5.6 billion respectively. In the event of a full-fledged trade war and higher duties, the ultimate gainers would be alternative suppliers such as Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay (in soyabean) and Brazil, Argentina, Ukraine and Russia (in corn). China and Mexico would simply switch to importing from these countries rather than the US.

And the losers? Obviously, farmers in the US “corn belt” states stretching from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Missouri to North and South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas: They are the ones growing the bulk of the country’s soyabean, corn and wheat. Apart from these midwestern US states, beef farmers in Texas and Oklahoma, milk producers in Wisconsin, New York and Idaho, and tree nut growers in California, Oregon, New Mexico and Georgia would suffer loss of export markets from any extreme tit-for-tat strikes.

America has a mere 1.89 million farms, as per the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) annual survey for 2023. That’s way below India’s 146.45 million agricultural holdings in the last Agricultural Census for 2015-16 and the roughly 105 million farmer beneficiaries of the PM-Kisan Samman Nidhi income support scheme.

But despite constituting less than 2% of the US population, farm and ranch families carry significant political voice. In the 444 counties labelled as “farming-dependent” by the USDA, Trump bagged 77.7% share of the popular vote in the 2024 Presidential election.

Story continues below this ad

A Financial Times report (‘US farmers “prepare for the worst” in new Trump trade war’, February 7) quoted an Iowa farmer as saying that “trading relationships go up on a stairway, where you work hard to build them up, but go down on an elevator – very, very fast”. He also expressed worry about the “long-effect” that countries “will no longer see us as a reliable partner”.

Implications for India

India isn’t a big market for US farm produce. According to USDA data, Indian imports of agricultural and related products from the US were valued at $2.4 billion in 2024. The bulk of it comprised tree nuts ($1.1 billion), followed by ethanol ($441.3 million), cotton ($210.7 million), forest products ($93.8 million) and pulses ($73.4 million).

India’s exports of farm products to the US were higher at $6.2 billion, dominated by seafood ($2.5 billion), spices ($410.4 million), rice ($395.4 million), baked goods, cereals & pasta ($243.3 million), processed fruits & vegetables ($227.7 million), and essential oils ($212 million).

To the extent that India has an agricultural trade surplus with the US, there might be pressure from the Trump administration to further open up the country’s market to American imports. India is already the largest market for US tree nuts, with $868.15 million worth of almonds and $129.74 million of pistachios getting imported during 2023-24 (April-March).

Story continues below this ad

US farmers have a lot to lose from a protracted trade war. India may also feel some of its effects, as more of a seller than buyer of agricultural produce.