At Pune’s FTII, one more in a long line of controversies

India's top film institute has too many students, too few teachers and, allegedly, too little freedom.

Gajendra Chauhan

Gajendra Chauhan

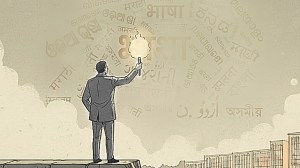

The ongoing protest at Pune’s Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) over the appointment of Gajendra ‘Yudhishthir of Mahabharat’ Chauhan is in a line of controversies that have rocked the seemingly tranquil campus over the past several years. FTII, nursery of some of the best TV and cinema India has produced, has ironically lost the plot repeatedly — over course backlogs and outdated syllabi, dismal student-teacher ratios and hostile student-faculty relationships, turf wars over creative freedom, and alleged political interference, compounded by an apparent lack of understanding of the institute’s core strength by the union Ministry of Information & Broadcasting.

It was to address several of these festering problems, in fact, that the Information & Broadcasting Ministry had, in 2010, contracted Gurgaon-based Hewitt Associates for a report on how to revitalise and upgrade FTII. The private consultant’s prescription to upgrade FTII to “international standards” was to re-model it as a public-private partnership, with expensive, profit-generating short term courses.

[related-post]

The suggestion met with vehement opposition on campus. Students argued it would make FTII homogeneous and exclusive, only for those who could afford the fees. Also, that it would merely train professionals for jobs, and curb the organic growth of creative persons. They suggested that a committee with members associated with the industry — and not a corporate analyst — should draw up the blueprint for FTII’s future. Subsequently, the P K Nair Committee was formed — with individuals such as Kundan Shah, Nachiket Patwardhan, Saeed Mirza, Shama Zaidi and Jabeen Merchant, and staff and students of the institute on it.

The draft report that the Nair Committee submitted over four years ago focussed on the key problem of backlog of courses. There were about 150-200 extra students on campus, as most three-year courses like direction and editing had stretched on for five or six years. Apparently the students did not finish projects on time, and the faculty and administration did not push them hard enough to meet deadlines.

The committee strongly recommended that admissions be frozen for a year or two at least — but even taking that decision took three years, and it was only in 2014 that the authorities could finally stop admissions to the flagship post-graduate courses. It was the right move, but it resulted in a loss of revenue for the institute, and widespread disappointment among prospective students. Because the decision was delayed, the backlog and overcrowding continued in classes and hostels, with some students from as old as the 2008 batch still on campus. And admissions have opened again this year.

The last convocation at FTII was held 17 years ago, in December 1997. Dilip Kumar was chief guest. Student protests led to convocations being scrapped altogether. The convocation before 1997 had been held in 1989. Last year, the institute announced diploma certificates would be issued to students who had completed courses between 1995 and 2006. Incidentally, 1997 was the last year diploma certificates were issued.

A new syllabus — under revision for six years — is likely to be introduced this year, but there is already talk it is not really going to be different from the earlier one. At 30 teachers to 400 students, the teacher-student ratio remains lopsided, especially for training that involves a lot of one-to-ones. Contract teachers are 60%-70% of the faculty. Some regular appointments were approved last year, but no recruitment has happened.

Over the past two decades, FTII has seen only three full-time women teachers. All the current 21 full-time teachers are male. Two years ago, the faculty were advised in a particular month to take their salaries as personal loans from banks, the interest for which FTII would pay.

This odd arrangement notwithstanding, finances are probably the one bright spot at FTII currently. The Planning Commission sanctioned Rs 80 crore last year, and new studios are currently being built. Last year’s Budget said FTII would be a Centre of National Excellence — even though not much has happened by way of follow-up.

A perennial complaint at the institute is about the government’s alleged refusal to uphold creative freedoms. A bureaucrat, rather than a film personality, has headed the school for the last 15 years — and critics insist civil servants with limited tenures cannot be committed to far-reaching changes. In 2012, The Indian Express had accessed documents of a governing council meeting that showed only five out of 15 members present, with many having been granted “leave of absence”. This included Raghvendra Singh, Joint Secretary (Films), and C Viswanath, Additional Secretary and Financial Advisor, both from the I&B Ministry. The last film person to head the institute as its director was Mohan Agashe, who ironically, had to go following students’ protests over his attempt to restructure some courses.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05