70 years of Guinness World Records: How a famous Irish stout became synonymous with whacky achievements

The first Guinness Book of Records was published on August 27, 1955 and sparked a worldwide curiosity about extraordinary record-breaking achievements. Here’s the story

On Wednesday (August 27), the Guinness World Records (GWR) turned 70.

The first edition, then known as the Guinness Book of Records, was published on August 27, 1955. Since then, GWR has gone on to become the primary international source for cataloguing an enormous number of world records.

It has sold over 150 million books globally in 40 languages, according to the organisation’s website. How did GWR come to be? And what does it take to enter the record book?

A book to prevent pub brawls

Arguments in pubs often tend to get messy and violent, especially when the hard stuff is involved. One such argument, though not in a pub, led to the birth of the GWR.

In the 1950s, Sir Hugh Beaver, Managing Director of the Guinness Brewery, was attending a hunting party in Wexford. There, he and his hosts argued about the fastest game bird in Europe. They could not find an answer in any reference book, and the drunken disagreement was left unresolved.

This sparked an idea for a Guinness promotional campaign: a book which would, once and for all, settle pub agreements. Guinness, arguably the most famous beer in the British Isles, already had a long history of imaginative marketing campaigns.

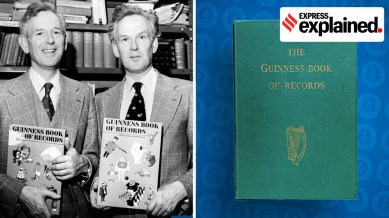

Guinness Superlatives (later renamed Guinness Book of Records) was incorporated on November 30, 1954, and the office opened in two rooms in a converted gymnasium on the top floor of Ludgate House, 107 Fleet Street, London. Sir Hugh invited two researchers, twins Norris and Ross McWhirter, to put together the record book.

The duo took almost 14 weeks to come up with the first edition, which was then distributed for free in more than 1,000 pubs across Ireland and the UK. While the McWhirters never answered Sir Hugh’s original question about the fastest game bird, they created a book that went on to become much more than just a marketing promotion for Guinness.

‘Officially’ popular: GWR’s enduring appeal

The first edition topped the bestseller list in the United Kingdom by Christmas 1955. This led to Guinness commissioning an updated version. Eventually, the project was expanded and took the form of yearly editions, in which all old records would be updated and new records would be set.

While originally just a yearbook, today, GWR has television shows across the world, as well as a robust online presence, with a huge social media following.

There are 68,523 active records in the GWR, including the routine, such as “world’s tallest building” (Burj Khalifa, Dubai), and the whacky, such as “longest fingernails ever” (Lee Redmond).

GWR today is a global brand, with offices in London, New York, Beijing, Tokyo and Dubai, with brand ambassadors and adjudicators on the ground around the world. Diageo, the parent company of Guinness, sold GWR in 2001. It is currently owned by the Canadian conglomerate Jim Pattison Group.

Entering the GWR

While some records are obvious (for example, “world’s tallest man”), others might be less so. As GWR has expanded, so has the number of records it documents.

Today, GWR has over 75 adjudicators across the world, who determine whether a record has been broken or not. There is even an application process – one can apply to invite an adjudicator to witness a record being broken. However, there are some strict criteria that make a Guinness World Record. A record must satisfy ALL the following criteria to count:

-

It should be objectively measurable;

-

It should be breakable — it cannot be something so unique that only one person can do it;

-

It should also be standardisable with a possibility to create a set of parameters and conditions that all challengers can follow;

-

It should be verifiable;

-

It should be based on only one variable;

-

It should be the best in the world. For any new record, GWR sets a minimum standard that has to be met for the record to be broken.

Story continues below this ad

In 2024, GWR received 48,295 applications from 189 countries, although only 3,324 were approved.

Ethical concerns

Since 2008, GWR has orientated its business model towards inventing new world records as publicity stunts for companies and individuals. This throws up several ethical concerns.

In 2019, British-American comedian John Oliver lambasted GWR for taking money from authoritarian governments for pointless vanity projects. Oliver was specifically referring to the 2015 GWR entry to the government of Turkmenistan for “most people singing in a round” (4,166 participants), which he alleged was a propaganda project of the country’s dictator, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov.

In 2024, GWR was accused of laundering the reputation of oppressive governments in the UAE and Egypt. Research by The Times, London found that “UAE can boast of 526 records after the gulf state spent millions of pounds on paid-for consultations to generate favourable publicity. Of these, 21 are credited to the region’s police forces including the Abu Dhabi police department’s certificate for “most signatures on a scroll”.”

GWR has also been criticised for encouraging people to partake in risky activities. In recent years, GWR has thus rescinded several of its old records which caused harm to animals, endangered the person or spectators, caused food waste, etc.