Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Make No Bones

Kahkashan and Mohammad Shariq make camel bones come alive.

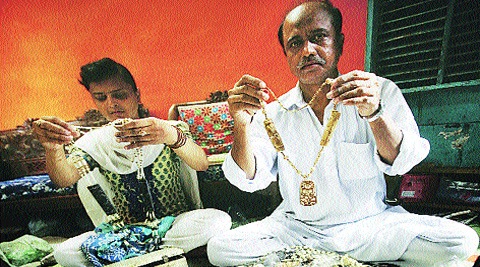

The artisans with their camel bone designs. (Source: Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

The artisans with their camel bone designs. (Source: Express photo by Praveen Khanna)

A little over a month from now, artisan Kahkashan and her husband Mohammad Shariq will be caught in the midst of hectic activity. After sacrificing a goat, distributing the meat and cooking biryani and kebabs on Bakri Id, they would have to collect what sustains their work the entire year — camel bones.

The couple makes jewellery, boxes, paper cutters and other gift items from camel bones; prices range from Rs 50 (bracelets) to

Rs 5,000 (curtains made of bone figurines). “Those who sacrifice camels on Bakri Id sell the animal’s skin and bones to artisans. Since there’s hardly anyone else working with bones, many individuals come to us to sell the bones,” says 42-year-old Kahkashan. They buy over 200 kg of bones at Rs 400 a kg.

Then starts the long and tedious work of stocking and processing the bones. The couple employs 7-8 people for this. “The bones have to be boiled several times. The first boil removes all the dirt and impurities. A couple more rids them of the smell and the oily texture. Finally, we have to reach the right density so that they are soft enough to be cut in the shapes so we can carve designs on them,” says 54-year-old Shariq, who does most of the carving. Kahkashan, gives the final touch in designing the jewellery using camel bone pieces, beads and terracotta.

The cutting, too, takes time. Shariq shows a paper cutter made with leg bones. “It has been cut to perfection with a single piece of bone, there are no joints,” he says. However, some buyers have reservations. “Vegetarians or people from the Jain faith don’t even stand near our stall at exhibitions. We keep our bone work separate from the other stuff we do, such as white metal, beads and terracotta,” says Kahkasha.

The art of carving runs in the family and they learnt the craft as children. The family did ivory work earlier, but when ivory was banned in 1989, they started using sandalwood. “But that too became expensive and about 20-25 years back, we began work on camel bones. But our designs are the same. What my father used to do with ivory, I do with camel bones,” says Shariq, who takes a break to attend a call.

He is back with a smile as his visa to Egypt has been confirmed; his bags are already packed. The couple often takes their work abroad under various government schemes. Kahkashan leaves for Muscat this December.

The art is their lifeline. “In a way, this is why we were married. My husband and I are distant relatives. Since both of us were good at this work, and marriage was possible, hamare rishtey ki baat chal gayi (the marriage proposal came up),” says Kahkashan. She hopes her daughter, Aksa, and second son 14-year-old Osama will take their work forward.

Though they do not have a shop of their own, it helps that they own a four-storey house in Daryaganj, where they have a workshop and a store. A small room on the third floor hosts basic furniture and an aqua-colour air cooler. The orange walls and the yellow almirah, though, are as bright as the happy faces around.

Contact 9999345827