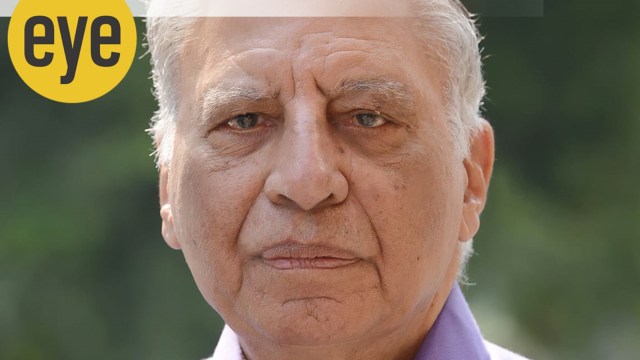

Keki N Daruwalla was not just a feted artist, he was that rare breed — a real poet

“I first read him in 1989 when I was in college. Struck by his sinewy, vigorous verse and the ease with which it traversed the sweep of history, I could see why he was a major figure in Indian letters.”

Keki Daruwalla was not just a feted artist, a man who lived long enough and in the right place and moment to corner the right prizes. He was that rare breed: A real poet. (Credit: Poetry Foundation)

Keki Daruwalla was not just a feted artist, a man who lived long enough and in the right place and moment to corner the right prizes. He was that rare breed: A real poet. (Credit: Poetry Foundation)‘Twas brillig and the slithy toves/ did gyre and gimble in the wabe’. Lewis Carroll’s lines of sparkling incomprehensibility came to mind when I met Keki Daruwalla this April. While he was alert, his speech — because of his illness — was unintelligible. And yet, the enunciation was clear, the tone crisp, the pauses considered, and the clause construction impeccable. As writer Alok Bhalla and I read his own poems to him, he leaned forward, his eyes alive with excitement.

Keki had lost his speech. He had not ceased to be a poet. I first read him in 1989 when I was in college. Struck by his sinewy, vigorous verse and the ease with which it traversed the sweep of history, I could see why he was a major figure in Indian letters. He had been catapulted to literary fame with his very first book, Under Orion (1970). Nissim Ezekiel had lauded his “mature poetic talent… literary stamina, intellectual strength and social awareness” — high praise from an older poet and exacting critic. He had already won the Sahitya Akademi Award (1984) and the Commonwealth Poetry Prize (1987). Those honours, coupled with the technical confidence and imperious tonal flourish of his verse made him seem formidable.

It was decades later that Keki became a friend. It began with emails about poetry, and later burgeoned into conversations, interspersed with cheerful literary gossip, over IIC ginger pudding. I grew to admire more than the poetry — his generosity of spirit, his dignity, his stout political integrity, and steadfast approach to human relationships.

The anecdotes were never self-aggrandising. Indeed, Keki was probably one of the last of the self-deprecatory poets — a precious, fast-dwindling tribe. He once laughingly mentioned that until 25, he saw himself “more as a cricketer” than poet. In 1964, as a young poet, he sent a bunch of poems to Ezekiel from Joshimath. Routed via Srinagar, Garhwal and Rishikesh, the mail took 15 long days to reach Mumbai: “Nissim wrote a nice courteous inland letter (in response), though later he came down to postcards. He would write about this and that, but regarding my poetry, he (had) nothing much to say. If I’d been him and seen those poems, I’d have been much ruder! He was very polite.”

About Arun Kolatkar, the understatement was masterly: “When I did an anthology of Indian poets… Arun never bothered to reply until I did a reading at The PEN… He came for that and said that not answering my letter was inexcusable. He gave me the rights to his poetry. But he didn’t stay for the reading!”

There was a vulnerability, too. He once explained why it took him time to start interacting with other poets. “Possibly I was self-conscious and shy, and refrained from mingling with the literary crowd, because of my police background.” (He had a distinguished career with the IPS, which he joined in 1958, and often contemplated writing a memoir about those eventful years.)

I once asked Keki what poetry meant to him. “Solace for the soul,” he said after a pause. “A valve… (releasing) the pressure of a strong emotion, a haunting image… There is a great relief… and exhilaration — till you read a few days later the wretched stuff that you wrote!” He read widely, choosing to start the new year or any important occasion (including his late wife’s birthday) by reading verse. “If I am really feeling out of sorts, I go back to poetry — Rilke, Akhmatova, Elytis, Auden, Ritsos, sometimes Paul Celan.”

His last book, Landfall Poems (2023), contained some of his finest verses. Unlike many others, Keki never lost his creative vitality. His signature strength remained his capacity to combine the panoramic and the particular, the balladeer’s impulse with intimacy. He could casually weave Greek myth, Dante, the emperors Cyrus and Ashoka into terse, bristling modern verse. But he could also speak of his silence when his mother asked him if he remembered his grandmother.

He was conscious of the criticism that he wrote only of “incidents”, not the interior landscape. His later work worked at rectifying that. Journeys, for Keki, were no longer just epic. They now hinted at self-implication: ‘Now my dreams ask me/ if I remember my mother/ and I’m not sure how I’ll handle that./ Migrating across years is also difficult.’

Keki Daruwalla was not just a feted artist, a man who lived long enough and in the right place and moment to corner the right prizes. He was that rare breed: A real poet.

“A people’s past is only safe with bards,” he once wrote. A people’s future, too, I want to add. Friend, map-maker, warrior poet, your work will endure. The “dripping deciduous word-leaf” will continue its “never-ending fall from the tree”.

The lyric will leaf on.

Subramaniam is a poet and author

- 0115 hours ago

- 0215 hours ago

- 0315 hours ago

- 0415 hours ago

- 0516 hours ago