Amit Kamath is Assistant Editor at The Indian Express and is based in Mumbai. ... Read More

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

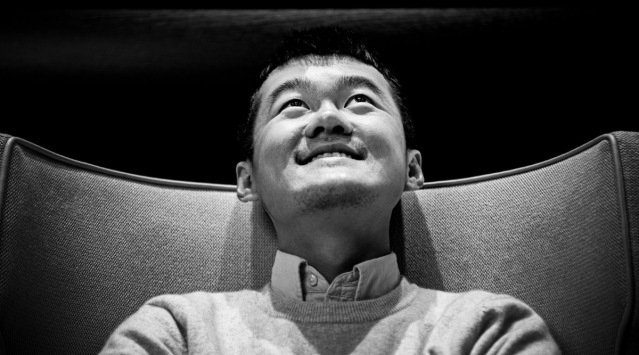

Ding Liren reacts after becoming the 17th world chess champion. (Photo: FIDE/Stev Bonhage)

Ding Liren reacts after becoming the 17th world chess champion. (Photo: FIDE/Stev Bonhage) There is a Mikhail Tal quote that everyone in chess is enamoured by: “You must take your opponent into a deep, dark forest where 2+2=5, and the path leading out is only wide enough for one.”

On Sunday, Ding Liren was the man emerging from the forest, the crown of the 17th world champion resting on his head, while one suspects Ian Nepomniachtchi is in there somewhere, probably still working out how he had lost to an opponent who was not even supposed to be in Astana.

Consider this: If Sergey Karjakin had not gone about cheering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he would not have been suspended by FIDE, thus making him ineligible from the Candidates Tournament in 2022. With Karjakin’s exit, the door opened for Ding, who had spent a lot of the pandemic years at home playing online.

Then, as Nepo claimed another shot at the world title through the Candidates Tournament, the reigning world champion, Magnus Carlsen, seemed to run out of motivation. As he forfeited his right to defend his throne, the door once again opened kindly for Ding.

He gratefully entered, and was possibly enveloped by an acute case of imposter syndrome instantly. He switched hotels a day before the first game because his room felt uncomfortable. He felt equally ill-at-ease at the playing arena, preferring to spend his time alone in the freezing solitary confinement of his private lounge. He looked cold. His game looked jittery.

“I didn’t think about chess so much at the start of the game. My mind was very strange. Strange things happened. I thought maybe there was something wrong with my mind. I’m a bit depressed,” he said after Game 1, revealing to the world — and his opponent sitting next to him — deeply personal things that only his psychologist ought to know.

His halting answers at the press conference made many people ask him if he needed a translator. Back in his hotel room, his team wondered if he needed medical intervention.

But as the 2023 world championship aged, Ding grew. In confidence and in stature. No doctors or translators were required. The Chinese GM even learnt how to deflect the uncomfortable questions from the media, like when he was asked about his entire preparation for the World Championship leaking online.

As his confidence grew, games he played with white started to get unpredictable: of the six games which ended with one player winning, four were with Ding making the first move. Words like gladiatorial are seldom used for chess players, these brainiacs who compete wearing bespoke suits, while sitting in air conditioned halls, on chairs that they handpicked after some serious consideration. And when they get tired of looking at their opponent, they retreat to their private lounges, with sofas to lie on and comfort food to munch on.

But no one who saw Game 14 in its near-seven-hour entirety would grudge Ding and Nepo that title. So deep had they retreated into the forest mentally which Mikhail Tal speaks of, that at some point Nepo made faces at his own pieces and cursed at them. Then, like the young chess prodigy Beth Harmon in Queen’s Gambit, he stared at walls like he could see a hologram of the board being projected there.

This is what seven hours of solitary confinement within your own thoughts, without exchanging any words with the rest of the world and barely any eye contact will do to you. After six hours had passed in Saturday’s game, both players resorted to sneaking glances at each other, which seemed to enquire: “Enough? Or you want some more?”

As both players soldiered on for some more, five-time world champion Viswanathan Anand tweeted: “I feel exhausted just watching them.” Over in the commentary, GM Daniil Dubov remarked: “I’m not sure what they’re fighting for exactly.”

In the end, when the draw was agreed upon, both players just sat there to discuss tactics, knowing well that in a few hours, they would be back at the same place resuming the contest in a different format: rapid.

It’s perhaps one the most unique elements of the way chess picks its world champion. A game at the world championship can last seven hours, like on Saturday. Or one hour, as three of the rapid games on Sunday did. The first 13 classical games had gone on for any duration between two hours to six hours.

After what seemed like a lung-bursting photo-finish to a marathon that was run over 20 days, Ding emerged victorious on Sunday. In the first few minutes, he sat rooted to his chair, his face hidden partially in his palm. “It was a very emotional moment when I won. I know myself, I knew I would cry and burst into tears. It was a tough tournament for me,” he later said.

His predecessor, Carlsen, had jumped into the hotel pool fully clothed in 2013 when he had first become the world champion. How would Ding celebrate? “I’d like to travel. When I have some spare time,” said Ding, who added he wanted to go to Turin to watch his favourite team, Juventus, play.

Finally, he was asked at what age he had begun to dream of being the world champion, a crown only 16 men before him — none of them from China — had worn. “I never dreamt of becoming world champion. For me it’s not so important to become world champion. I always wanted to become the best player in the world.”