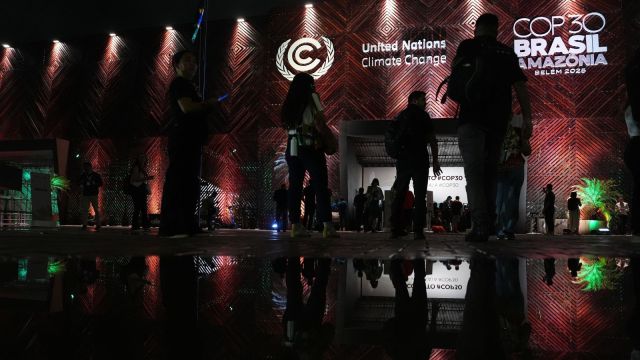

The message from COP30 is clear: The world has overshot the 1.5°C threshold and the window for action is closing fast. With the Paris Agreement failing to generate the scale of ambition required, the demand for a Global South-led climate multilateralism is now pressing. In this context, we — parliamentarians from the most climate-vulnerable South Asian countries — propose regional climate multilateralism. This would allow South Asian nations to pool scale, resources, knowledge, and financial/technological capabilities in diverse sectors.

By 2050, South Asia could face losses of nearly 1.8 per cent of annual GDP due to extreme heat, sea-level rise, floods, and droughts, along with irreversible losses to lives, livelihoods, and cultural traditions. Interconnected ecosystems make the region uniquely positioned to act collectively.

It is essential for South Asian countries to establish institutional mechanisms that enable mutually beneficial climate action. A decisive step would be setting up a regional body — potentially named the South Asian Climate Cooperation Council (SACCC). Past failures in regional institution-building should not deter us. Regional cooperation during crises is not new. The Quad emerged following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. South Asian countries have supported each other during disasters like the Nepal earthquake and the Maldives water crisis.

One area where progress exists is cross-border energy cooperation. The 2014-SAARC Framework Agreement for Energy Cooperation provided a basis for regional electricity trade. A trilateral power transaction — from Nepal to Bangladesh via the Indian grid — is operational, and the One Sun One World One Grid initiative offers space for deeper energy pooling among India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal.

Three pillars can guide the proposed SACCC. First, a regional knowledge and innovation hub. Co-managed centres across South Asia can harness complementary strengths. Maldives could host a coastal climate resilience hub focused on coral restoration, fisheries, and renewable energy for maritime areas. Sri Lanka’s experience with 30×30 and Life to Our Mangroves can strengthen nature-based solutions. Bhutan’s Gelephu Mindful City and India’s Mission LiFE can help scale sustainable urban and behavioural transitions. India’s technical expertise can support regional renewable energy expansion and grid integration.

Second, a South Asia green climate finance facility. Implementation depends on accessible finance. A regional financing mechanism would pool resources, enhance the ability to absorb international funds, and build a robust pipeline of high-priority, bankable projects. Working with institutions like ADB, World Bank, or Green Climate Fund, the facility could issue bonds, offer risk-mitigation instruments, and design regional project portfolios to attract climate investment.

Third, a scientific commission for South Asia that would provide independent, evidence-based guidance on the type, scale, and speed of climate action needed. It would identify low-cost, high-impact interventions; support R&D; promote data sharing; and leverage institutional excellence across countries. A homegrown South Asian institutional response can drive both peaceful coexistence and the co-creation of a more prosperous, climate-secure future.

The authors are MPs from India, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Maldives respectively