📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

Little Big Magazine

A rich selection of writings from The Modern Review, the 1940s journal that shaped the idea of India.

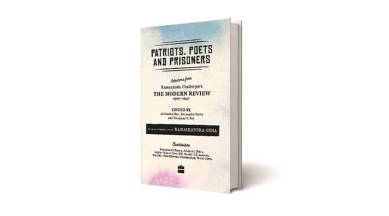

Name: Patriots, Poets and Prisoners: Selections from Ramananda Chatterjee’s the Modern Review, 1907-1947

Edited by Anikendra Nath Sen, Devangshu Datta and Nilanjana S Roy

Publication: Harper Collins

Pages: 352

Price: Rs 450

Chatterjee conceived The Modern Review as a journal that spoke of, for, and to the emerging Indian nation. He had already achieved eminence as a journalist with Prabasi, the Bengali journal he was editing while also working as principal of the Kayastha College in Allahabad. His biographer, Nemai Sadhan Bose, writes that Chattterjee felt only a periodical in English could speak for the whole of India and foster the idea of national unity. The first issue had contributions from writers from across India, among them Sister Nivedita, G Subramania Iyer, EB Havell and Jadunath Sarkar. The journal was expectedly rich in political commentary, but it also published poetry, fiction, book reviews (including of those published in different Indian languages), and pioneered studies on Indian art. In his remembrance, Jadunath Sarkar wrote, “He (Chatterjee) laid the greatest emphasis on India’s economic problems, her art old and new, and the facts of her historic past dimly known before. In the very first number of his Review, out of 15 articles, three were on economics, two on art, two on Indian history and only one on politics…” Sarkar writes that Chatterjee was the first editor to pay serious attention to Indian painters by the generous provision of three-colour blocks and black-and-white illustrations of their work along with studies of their lives and criticism of their style. The Modern Review came to be about a people, though under foreign rule, reflecting on their destiny and expressing their creative selves. It reflected the spirit of its times — every major debate about the future, present and past of India was reflected in its pages. Chatterjee was associated with the Hindu Mahasabha, and once presided over its annual conference, but felt, like any great editor, that a hundred views would make his publication exciting and the public discourse democratic.

So, we have Lala Lajpat Rai powerful polemic on what ought to be the shape of the struggle for Swaraj (‘The National Outlook’), Mahatma Gandhi’s defence of ahimsa in response to Rai’s contention that the creed of non-violence led to India’s downfall (‘On Ahimsa: A Reply to Lala Lajpat Rai’), Rabindranath Tagore’s critique of Gandhian politics (‘The Cult of Charkha’ and ‘Striving for Swaraj’), Sister Nivedita’s argument for a free India (‘India and Democracy’) and so on. Subhash Chandra Bose was a prolific contributor, writing not just essays, but also sending regular reports and commentaries on developments in Europe. His ‘My Strange Illness’ is a genre-transcending article, written against the background of the turmoil in the Congress in 1939, the year Bose was re-elected party president. A narrative in the first person, it hints at the rampant factionalism and mistrust prevailing then in the Congress.

An article that has immense relevance for our times is ‘We Want No Caesers’ that Jawaharlal Nehru wrote under a pseudonym, Chanakya, in 1937. Nehru, in an impartial tone, dissects the conceits of the “public man”. It is a warning against the mass adulation that can turn him into a despot. He writes, “Jawaharlal has learnt well to act without the paint and powder of the actor. With his seeming carelessness and insouciance, he performs on the public stage with consummate artistry. Whither is this going to lead him and the country? What is he aiming at with all his apparent want of aim? What lies behind that mask of his, what desires, what will to power, what insatiate longings?” Nehru wrote this in the context of having been Congress president for two terms. “Caesarism is always at the door”. We want no Caesars, he concludes.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram