Looking for tigers in an Uttarakhand village: Fresh paw prints, near-misses and an injured bull

Two deaths from tiger attacks in less than a week has set off fear and panic in villages across Garhwal bordering the Jim Corbett National Park. A day in the life of a village living in fear as officials work to trap the big cat

A three-tier machan being made in the fields outside Virendra's house in Dalla village on April 19. The bottom tier was to provide support, the middle tier for the veterinarian to position himself with the dart gun and the upper tier to provide cover and shelter to the shooter. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

A three-tier machan being made in the fields outside Virendra's house in Dalla village on April 19. The bottom tier was to provide support, the middle tier for the veterinarian to position himself with the dart gun and the upper tier to provide cover and shelter to the shooter. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra) FOR A few tense seconds, the prey, a brown goat, and the predator locked eyes. Muscles twitched, the tiger looked like it would walk into its trap — a cage carefully rigged to close on its own — when two dogs started barking. The tiger, forest officials who were there say, walked away.

The detailed plan, set in motion over the last several hours on April 19, had failed. A new plan was required. And for the terrified residents of Dalla village in Pauri Garhwal’s Rikhnikhal tehsil, a longer wait before the tiger is caught.

Screenshot showing the tiger walking toward the cage. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Screenshot showing the tiger walking toward the cage. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Days since a tiger mauled a 65-year-old man to death in the area and killed another over 20 km away, teams of the state forest department have been deployed at the two spots to trap the big cats.

Forest officials say there are two tigers on the prowl in Dalla that have been spotted several times in the village since April 11.

Villagers say the conflict began two days later, when one of the tigers attacked a cow.

“We saw the tiger grabbing the cow by its neck. It was around 3 pm and luckily, 8-10 of us gathered with lathis. This was the first time I was seeing a tiger this close to me. It was scary, but we somehow managed to chase it away. But it returned within 15 minutes. We again chased it, but five minutes later, we heard cries for help. The tiger had attacked Virendraji,” says Ram Singh, 40, a resident of Dalla village.

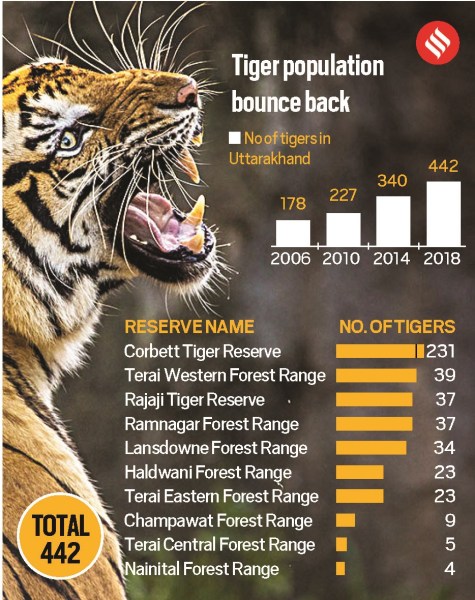

Virendra Singh Rawat, 65, lived in Dalla with his children and grandchildren. His house was built 35 years ago in one of the less populated areas of Dalla, a village of 40-odd families that is around 10 km from Jim Corbett National Park. Forest officials say the tigers most likely strayed from the Park, which is home to over 230 of them.

A machan being set up. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

A machan being set up. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Virendra’s house, perched at the edge of a hillock, has open fields in the front and steep hills at the back. The nearest house is over 150 meters away. In the absence of roads or a clear trail, the only way to reach the area is to trek uphill through slippery pathways and navigate one’s way through wild bushes and stone boulders for around three kilometres.

“Virendra ji was grabbed by the neck and dragged uphill around 30 meters. We all gathered and for around 90 minutes, the tiger stood right there with the body. We finally started a fire and threw some torches at it. When the tiger backed down a few metres, some of us risked our lives and dragged Virendra back. But he was long gone — his upper body was all mauled,” says Ram Singh.

Two days later, at Simli village in Dhumakot tehsil, over 20 kilometers from Dalla, Ranveer Singh Negi, 75, was killed by a tiger. Forest officials said Negi, a retired education department employee, lived in a house close to the forest. His body was recovered the next day, around 100 meters from the house.

Even for a region that has grown up on tales, both apocryphal and real, of the legendary Jim Corbett and his hunting prowess, the recent killings have left Dalla and nearby villages shaken. Confirming that both the deaths were the result of tiger attacks, the Pauri administration imposed a night curfew in Dalla and Simli, along with around two dozen others. These villages are now under night curfew and residents have been told to avoid daytime movement until the tigers are caught.

Dehradun Zoo veterinarian Dr Pradeep Mishra (left) and and Pauri Garhwal District Forest Officer (DFO) Swapnil Aniruddha (second from left) with forest officials, rangers, foresters and guards at Dalla village. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Dehradun Zoo veterinarian Dr Pradeep Mishra (left) and and Pauri Garhwal District Forest Officer (DFO) Swapnil Aniruddha (second from left) with forest officials, rangers, foresters and guards at Dalla village. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Two attacks, 20 km apart

The forest team stationed at Dalla has two veterinary doctors — Dr Pradeep Mishra of Dehradun Zoo and Dr Amit Dhyani of Haridwar Rescue Centre — along with forest rangers, several foresters, and guards.

Pauri Garhwal District Forest Officer (DFO) Swapnil Aniruddha, who is in Dalla to monitor the team, said it is yet to be confirmed if the killings in Dalla and Simli were by the same tiger. “At this point, we cannot say with full certainty if the same tiger is responsible for the two incidents. While no tiger has been spotted in Simli since the incident, there have been regular sightings in Dalla village. Tigers do travel around 35 kilometers in a day, but it is highly unlikely that a tiger would have traveled 20 kilometers to Simli and returned. We have deployed teams in both places to catch the tigers,” he says.

Pauri Garhwal District Forest Officer (DFO) Swapnil Aniruddha keeps a watch on the machan from the roof of Virendra’s house. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Pauri Garhwal District Forest Officer (DFO) Swapnil Aniruddha keeps a watch on the machan from the roof of Virendra’s house. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

“In the first case, the victim’s face was badly mauled, and we were able to recover saliva samples of the killer. In the second incident, we found the tiger’s saliva mixed with blood and some hair. We have sent samples from both sites for testing at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology in Hyderabad. Based on the DNA results, we can confirm or deny if the attackers in both the cases are the same,” he adds.

The forest team had arrived in Dalla on April 15, two days after Virendra was killed, and set up their camp in the verandah of the victim’s house and in the fields outside. The team had struggled to haul the 5-tonne tiger cage through the rough terrain.

It was a struggle for the forest team to haul the 5-tonne cage through the rough terrain in Dalla village. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

It was a struggle for the forest team to haul the 5-tonne cage through the rough terrain in Dalla village. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

By noon on April 19, the day Aniruddha reached the village, another smaller cage, used to catch leopards, had been placed alongside to catch the second tiger. After the failed attempt earlier that day, of trying to bait the tiger into walking into the cage, the officials had decided to tranquilise it.

A smaller cage, used to catch leopards, was placed alongside the big one on April 19 to catch the second tiger. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

A smaller cage, used to catch leopards, was placed alongside the big one on April 19 to catch the second tiger. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Within an hour, a three-tier machan had come up in the fields outside Virendra’s house. The bottom tier was to provide support, the middle tier for the veterinary doctor to position himself with the dart gun and the upper tier to provide cover and shelter to the shooter. “Usually, the veterinarians sit in closed vehicles to dart the targets, but given the terrain, bringing a vehicle was not an option here,” says Aniruddha.

“Based on what we know so far, there are two tigers. One appears to be older, slightly bigger and has a full tail. The other is younger, smaller, and has a broken tail. I have asked Dr Mishra to look for and monitor the full-tailed tiger, and Dr Dhyani to focus on the other one,” says Aniruddha, as they all got ready for a meal of daal-chawal cooked by the villagers.

Virendra’s grandchildren sit on the first-floor balcony, peering through the gaps in the strong metal grills. The forest department’s paraphernalia lay nearby — four rope coils, pieces of cloth and four large bamboo sticks, all to be put into use in the event of the tiger’s capture.

“We have discussed all possible options and we have decided that the first thing to do is to recce the nearby areas and see if there is a shortcut for us to carry the tigers if they are caught,” said Aniruddha.

Midway through the lunch, there is an alarm — there has been some movement in the fields, around 200 meters away. A troop of monkeys let out piercing shrieks. Binoculars and dart guns are drawn. For a few minutes, everyone on the verandah is frozen in mid-movement. It turns out to be another false alarm, one of many over the last few days.

In villages, fear, night curfew

Since the April 13 killing, life has been tough in Dalla. Like many other villages in the hills, Dalla is a village of mostly women, children, and the elderly, with men and most youngsters having migrated to the plains for work or education. Villagers say though most of them have ration stored for weeks, getting fodder for their cattle has been a challenge.

“My wife and I live here; my sons and grandchildren are in Kotdwar. We have been asked to lock ourselves up in the house before sunset and come out only during the daytime. Even then, we cannot go out in groups of fewer than five. We usually go to the forest to bring fodder for the cattle, but we can’t do that now. These poor things have gone hungry for very long,” sighs villager Pratap Singh, 66.

In neighboring Gadiyonpul village, Darshan Singh says most of the shops in the market have been shut since April 13. “This is a hill area close to the forests, and we are used to seeing bears, boars, and leopards. But I have never seen the kind of fear we see now,” says Singh, looking at an elderly villager walking down the road with a jute bag in one hand and a spear in the other.

In the neighboring Gadiyonpul village, an elderly resident walks down the road with a spear. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

In the neighboring Gadiyonpul village, an elderly resident walks down the road with a spear. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Over five kilometers from Gadiyonpul village, Sunita Devi, 40, and her daughter have locked themselves up in their house. With the nearest kirana store in Gadiyonpul, she is dependent on either the forest officials or the village locals for her ration and daily needs.

A long wait

Back in Dalla, the harsh sun has made way for long shadows and a pleasant evening – just the time tigers like to move around, says Aniruddha. At Virendra’s house, the forest team is ready for its next step.

The plan is to send veterinarian Dr Mishra to the machan to take his position on the makeshift platform with his dart gun. The day before, Mishra said he had locked himself up in one of the cages, staying on alert for an hour and a half with the dart gun. “The idea was that we would get a 360-degree view of the tiger’s movement, providing a better chance to tranquilise it. It, however, did not work,” said Mishra.

So today, a forest department gunner would accompany Mishra, while another team headed by Dr Dhyani is on standby. A WiFi-enabled night vision camera installed on the roof of the machan platform beamed images from the fields to Mishra’s phone.

A WiFi-enabled night vision camera was installed on the roof of the machan platform. The camera beamed images from the fields to Dehradun Zoo veterinarian Dr Pradeep Mishra’s phone. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

A WiFi-enabled night vision camera was installed on the roof of the machan platform. The camera beamed images from the fields to Dehradun Zoo veterinarian Dr Pradeep Mishra’s phone. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

As Mishra walks towards the machan, he stops at a stream barely 10 meters from the makeshift structure and bends down to look. There is a set of fresh paw prints by the banks — the tiger was close.

By 5 pm, everyone takes position. The teams are connected through walkie-talkies. The dogs that had thwarted the plan that morning had been locked up. From the roof of Virendra’s house, DFO Aniruddha keeps watch. “It’s not a good idea to use drones to monitor the area because they make a lot of noise,” he says.

Fresh paw prints spotted in a stream barely 10 meters from the machan. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Fresh paw prints spotted in a stream barely 10 meters from the machan. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Less than 10 minutes later, a tiger appears from the bushes, over 50 metres from the machan. Walking gracefully, its muscular shoulders bearing no sign of the stress that it had caused an entire region, it pauses to look at the machan platform that’s covered in green sheets. And then, continues walking.

“Tiger 2, Tiger 2, I have sighted the tiger. But it is not in my range,” Mishra’s whisper crackles through Aniruddha’s walkie-talkie. The tiger has moved further away from the platform, ignoring the cage and the bait. Everything goes silent.

“The dart gun could not be used as the tiger was not in the range of a clean shot,” Aniruddha says later, explaining why the vet hadn’t shot at the tiger.

Around 90 minutes later, a bull comes limping from a clump of trees and collapses a few meters from the house. Forest officials said the bull had been attacked by the tigers two days ago, but had escaped with injuries.

The sun has now set and it’s pitch dark, and the lights are turned on in Virendra’s home. “I think you should come back,” Aniruddha tells Dr Mishra on the walkie-talkie. “And let us bring the bull and try to save it. If it doesn’t survive, maybe we can use him as bait tomorrow.”

The house where Virendra Singh Rawat (65), who was killed by the tiger on April 13, lived in Dalla with his children and grandchildren. Dalla village is barely10 km from Jim Corbett National Park. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

The house where Virendra Singh Rawat (65), who was killed by the tiger on April 13, lived in Dalla with his children and grandchildren. Dalla village is barely10 km from Jim Corbett National Park. (Express photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

Later, as the team packs up, Aniruddha says, “This is a tiring job, requires a lot of patience. We are trying to catch an animal that is incredibly smart and unpredictable.”

“You must have heard about the efforts to catch a tiger in Ramnagar,” he continues, talking about an operation spanning six months in 2021-22 to capture a man-eater that was believed to have killed seven people. “That operation involved a team of over 100 officials from six forest divisions. It took them six months to catch the tiger. We have been here for less than a week,” he says, preparing to head to the forest department’s guest house where he will spend the night.

On April 26, a week after The Indian Express visited Dalla village, the bigger of the two tigers was captured from Jui village, 9 km from Dalla, after being tranquilised. Forest officials said the tiger would soon be transferred to a rescue centre before being sent to a tiger reserve.