Paris showcases artist Raza’s works in India and France

On board with fellow artist Akbar Padamsee, the voyage was spent pondering over books, practising how to knot a tie, chats on their aspirations for Indian art and themselves.

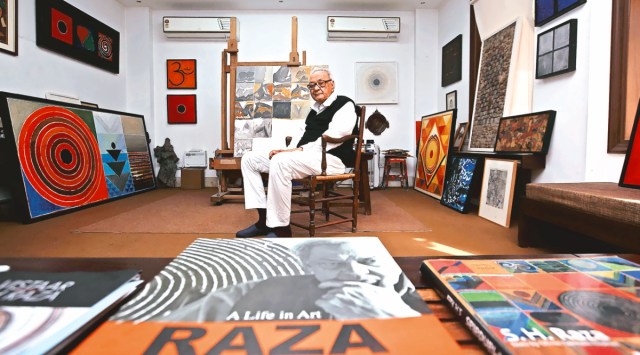

The largest-ever exhibition of SH Raza opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris on Tuesday featuring over 90 works from collections across the world. The Raza Foundation. Express File

The largest-ever exhibition of SH Raza opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris on Tuesday featuring over 90 works from collections across the world. The Raza Foundation. Express File In September 1950, when artist S H Raza set sail on the English boat headed from Mumbai to France, he had no inkling that his destination would become his home for the following six decades.

On board with fellow artist Akbar Padamsee, the voyage was spent pondering over books, practising how to knot a tie, chats on their aspirations for Indian art and themselves.

“I was received by Ram Kumar in Paris and almost immediately wanted to explore the city. I wanted to visit galleries, museums, look at art. There is so much that I wanted to know,” said Raza in an interview to The Indian Express in 2015, a year before his death in Delhi, where he only returned in 2010.

On February 14, through a collaboration between the two countries he called home, Raza’s largest ever exhibition opened at The Centre Pompidou in Paris. “We are very happy to celebrate the international artist who made great contribution to modern art, and the friendship between our two countries,” said Xavier Rey, director of Centre Pompidou at the inauguration of the exhibition attended by Ambassador of India to France Jawed Ashraf, and Ambassador of France to India Emmanuel Lenain.

Featuring over 90 works from collections across the world, the showcase, proposed by The Raza Foundation and curated by French art historian Catherine David, commemorates the late artist’s birth centenary in 2022.

Born in 1922 in Babaria in Madhya Pradesh, where his father was a forest ranger in British-ruled India, his undying quest to learn defined Raza’s journey from the forest village to Mumbai en route to Paris. When his entire family moved to Pakistan during the Partition, Raza stayed back in India.

Formally trained in art at the Nagpur School of Art, while his expressionist landscapes were to be influenced by the urban milieu of Mumbai in his early years, his desire to develop an avant-garde language for Indian art brought him together with his close associates — including FN Souza, MF Husain, KH Ara, SK Bakre and HA Gade — to establish the formidable Progressive Artists’ Group in 1947.

It was, arguably, a chance interaction with French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1948 in Kashmir, where he advised Raza to study the works of French post-impressionist Paul Cezanne to construct or structure his paintings better, that acted as a turning point in Raza’s career. Only 27 when he left for Paris on a French government scholarship to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-arts, he was already considered an artist of repute within India, having won travel grants, awards at exhibitions and numerous commissions.

“If you were to use the idiom of scapes, then Raza moves from landscapes to cityscapes to in-scapes, delving into the inner world… He used to say how to paint he learned from France and what to paint he learnt from India,” says Ashok Vajpeyi. managing director of The Raza Foundation.

The showcase in Paris contextualises this arc in chronological order. Straddling between Indian philosophy and tradition, music and poetry, French modernism and its lush terrains, the exhibition reflects on the diverse influences that defined Raza’s vast oeuvre.

The early works include his watercolours from the ’40s and experiments with life study at the Sir JJ School of Art in Mumbai. With his arrival in Paris, the French cityscapes become more dominant, as Raza responds to his travels in Europe, its cityscapes and churches, in tonal variations borrowed from Indian aesthetic traditions such as Rajasthani and Pahari miniatures, evident in works such as Haut De Cagnes (1951) and Sans titre (1952).

There was a further reconstruction of the landscapes when he switched to oil painting in the mid ’50s, working with a palette knife. Though he received critical acclaim, also becoming the first foreign artist to be given the prestigious Prix de la Critique in 1956 in France, Raza would make frequent trips to India where his artistic vocabulary was rooted.

If in Sans titre (D’Apres une Minature Indienne, 1957) he responds directly to Rajput miniatures, in the 1964 oil Udho, Heart is not Ten or Twenty he borrows a line from 16th century poet Surdas.

Substantiating his life and times are also several documents on view, including Raza’s earliest interviews, diary notes, catalogues, and letters written to his wife Janine Mongillat and friends, where discussions range from financial constraints to their personal struggles and artistic concerns.

The showcase ends with Raza’s trademark bindus that preoccupied his art from the ’80s, but perhaps also denote the very beginning of his endeavours – as a restless child he was asked by his primary school teacher in Mandla to stare at a dot drawn on the blackboard to discipline him. Raza never forgot that lesson. The bindu was to become what he described as “the force that awakened a latent energy inside”.