The election watchdog then began collating data for the Assembly elections held in Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and Karnataka. The Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat elections were announced separately, but results for both were on the same day in December 2017. The Karnataka elections results were announced on May 15, 2018, a day before the EC met with the Law Commission.

The outcome of the data collection exercise showed that, cumulatively, more than half — specifically 52% — of the 268 “no objection” references received from the Union and state governments during the three Assembly elections were replied to by the EC within 72 hours.

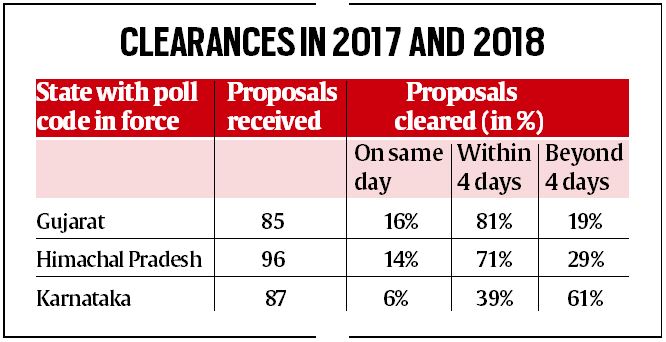

The clearance rate varied from state to state. According to the state break-up, disposal of government references, both from the state and Centre, were faster during the Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat elections in 2017. For instance, 81% of the proposals pertaining to Gujarat received from the Union and state governments were replied to by the EC within the first four days and 71% of the references pertaining to Himachal Pradesh were cleared during the same time (see chart). However, in case of Karnataka, 39% of the references were replied to in the first four days and the remaining took more than 4 days.

The EC shared this dataset with the Law Commission on June 8, 2018, as indicated by the correspondence accessed by this newspaper. This input, however, does not figure in the Law Commission’s interim or draft report on simultaneous polls released on August 30, 2018. The draft report states that the EC had submitted that only new projects or financial grants that can potentially influence voters are restricted during the MCC period.

ExplainedThe case against MCC

The ruling BJP has repeatedly underlined that imposition of MCC each time a poll is announced impedes governance and comes in the way of development work. This is one of its key arguments in favour of simultaneous polls. It has also been highlighted by the panel on ‘One Nation One Election’ led by former President Ram Nath Kovind.

“The ECI, in its communication to the Law Commission, has clarified that it does not refuse approval for schemes undertaken for dealing with emergencies, calamities, welfare measures for the aged, etc. The MCC is restricted to the constituency or the State which is going to the polls and not in other areas. However, it is understood that the various Departments of the Government refer even routine matters to the ECI as a measure of abundant caution,” the draft report states.

Story continues below this ad

The EC’s dataset does not specify the number of government references that were approved or rejected; instead, terms such as “cleared” and “replied” are used. However, an officer who was part of the data collation exercise at that time told this newspaper that the majority of government references typically consist of proposals deemed permissible by the bureaucracy during the MCC period and hence easily get the EC’s approval.

For instance, the references made by the Union government during the Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh elections include permission for broadcast of the Union Agriculture Minister’s message on World Food Day, 2017 and broadcast of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Mann Ki Baat programme in October 2017, visit of the Defence Minister to Himachal Pradesh and revision of wage rates under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

For the Karnataka elections in 2018, the Union government sought approvals for release of funds for the AMRUT mission in the state, another revision of wage rates under MGNREGA, continuation of release of new LPG connections under PM Ujjwala scheme in Karnataka, permission for running two special trains and release of subsidy for 80 electric buses of the Bangalore Municipal Transport Corporation under the FAME scheme of the Ministry of Heavy Industries.

Although the EC has never opposed the idea of simultaneous elections, it, very recently, put up a strong defence of the MCC in a communication shared with the Law Commission in March 2023. As first reported by The Indian Express on January 25, responding to a question by the Law Commission of India if periodic elections lead to a policy paralysis owing to the frequent imposition of the MCC, the Election Commission described MCC as a “vital instrumentality” in providing a level playing field to everyone, and “integral to the design of conducting free and fair elections and credible electoral outcomes”.

Story continues below this ad

The response is significant since it is the first time that the poll watchdog has so staunchly defended the MCC stating “it would not be correct” to view its application as a “disruption”.

The MCC is a code containing some general precepts for model behaviour during elections conducted by EC. It has eight chapters, with one dedicated to what the party in power can and cannot once elections are announced. It forbids use of official machinery and personnel for political gains of the party in power. Hence, the spirit of MCC also requires the bureaucracy or any public servant to not engage or appear to engage in an activity that could work to the advantage of the party in power.

The BJP’s argument in favour of simultaneous elections rests significantly on the frequent imposition of the MCC during frequent elections, citing its impact on governance. According to the BJP, the imposition of MCC leads to a standstill in development programmes and activities.

In its recent report recommending simultaneous elections, the high-level committee on ‘One Nation One Election’, chaired by former President Ram Nath Kovind, said non-simultaneous elections lead to the MCC being implemented four times in five years.

Story continues below this ad

“…the MCC affects the governance architecture in a significant way, severely disrupting it if elections are held asynchronously. In effect, it substantially dilutes the continuity of governance through the engagement of policymakers and the disruption in the decision-making process repetitively four times, instead of one,” it said.

In its submission to the Kovind committee, the BJP had cited frequent imposition of MCC due to asynchronous elections as an impediment to development work.