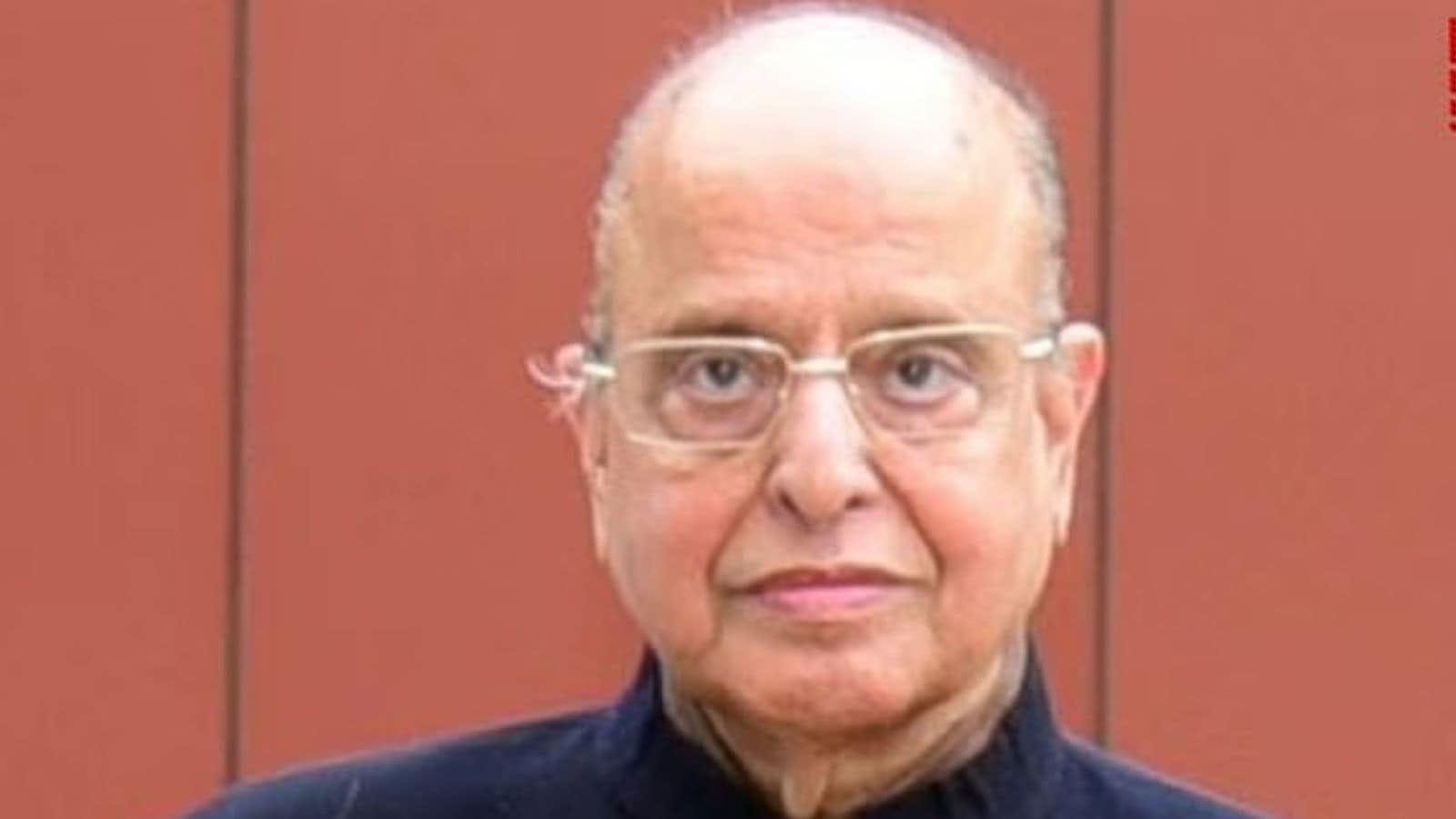

‘Father figure, promoter of science’: India remembers former Isro chief K Kasturirangan

On April 27, the Raman Research Institute (RRI) campus in Bengaluru will bear witness to his mortal remains, which will be kept there for the public to pay their last respects.

Kasturirangan, who passed away at the age of 84 in Bengaluru on Friday, will be remembered as a pioneering Indian scientist, a key policy architect, and above all, a friendly, smiling, and ever-approachable human being. (PTI)

Kasturirangan, who passed away at the age of 84 in Bengaluru on Friday, will be remembered as a pioneering Indian scientist, a key policy architect, and above all, a friendly, smiling, and ever-approachable human being. (PTI)He was “Kasturi” to his close friends and family, and “Dr Rangan” to his younger scientist colleagues. Active and energetic well into his 80s, Dr K Kasturirangan may have retired from the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) over two decades ago, but he never stopped working. As someone who never stopped thinking about how to elevate Indian science to the global stage, he supported mega-science projects and posed probing questions during scientific review and progress meetings. But his childlike enthusiasm remained consistent.

Kasturirangan, who passed away at the age of 84 in Bengaluru on Friday, will be remembered as a pioneering Indian scientist, a key policy architect, and above all, a friendly, smiling, and ever-approachable human being.

In his tribute to the former Isro chief, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said: “I am deeply saddened by the passing of Dr K Kasturirangan, a towering figure in India’s scientific and educational journey. His visionary leadership and selfless contributions to the nation will always be remembered. He served Isro with great diligence, steering India’s space programme to new heights and gaining global recognition. His leadership oversaw ambitious satellite launches and championed innovation.”

Until July 2023, when he suffered a heart attack during a tour in Sri Lanka, Kasturirangan was a regular at his office at the Raman Research Institute (RRI) in Bengaluru. It was common to spot him on the picturesque campus, especially during his post-lunch brisk walks—often at a pace unmatched even by those half his age.

On April 27, the same RRI campus will bear witness to his mortal remains, which will be kept there for the public to pay their last respects.

Kasturirangan was a mentor, a guide, and a well-wisher to many. Soft-spoken and persuasive, he had a unique ability to convince the government to take bold steps in space technology—especially at a time when major space-faring nations denied India access to critical knowledge. From the beginning, he worked tirelessly to make India self-reliant in space technology.

Science Minister Jitendra Singh, who also heads the Department of Space, called Kasturirangan a visionary scientist and a guiding force behind India’s space programme. “His contributions to ISRO and Indian science will be remembered for generations. Heartfelt condolences to his family and loved ones,” Singh said.

Speaking to The Indian Express, Pramod Kale, former director of the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, recalled his association with Kasturirangan since the latter’s early days as a student at the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) in 1964.

“Nearly 40 years ago, Kasturirangan was convinced that satellites could deliver data not only for India but for other countries too. He led the remote sensing satellite programme effectively. It was under his leadership that ISRO became capable of offering satellite-based services to the world,” Kale said.

Under Kasturirangan’s leadership (1994–2003), ISRO achieved significant milestones, including the successful launch and operationalisation of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). Later, the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV), too, tasted success.

During his tenure, one incident involved a last-minute abort of a scheduled GSLV launch.

“He stayed calm , composed and took the unexpected development in the right stride. We immediately formed teams to figure out reasons but throughout, Dr Kasturirangan remained cool and collected,” Kale recalled.

Professor Tarun Souradeep, Director of RRI, first met Kasturirangan in 2011 during a presentation on the proposed Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory-India (LIGO). And over the past three years, the two worked closely and became friendly associates.

“Our discussions surrounded what we could do next in science. He was open-minded, gave space for new ideas and disagreements and remained ever supportive. His was a reassuring presence in meetings and discussions,” said Souradeep, calling the loss deeply personal. The two last met a little over a month ago at Kasturirangan’s residence.

Kasturirangan maintained an interest in science across scales and wavelengths and never missed an opportunity to engage with teams and stay updated. S Seetha, a former ISRO scientist closely associated with the Astrosat mission, said: “It was due to Dr Kasturirangan’s constant interest and guidance that Astrosat—India’s first multi-wavelength space observatory—has been successfully operational for over nine years. He laid its foundation and followed its progress at every stage.”

Professor Annapurni Subramaniam, Director of the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) in Bangalore, described Kasturirangan as someone with “an unlimited pool of drive.”

“Dr Kasturirangan would utilise every minute, engage in brain-storming sessions over breakfast or lunch. He would push people to work and contribute. He had a great ear for details of the projects and would be actively involved in meetings. I distinctly recall his keen interest in some of the science that the Aditya L1 mission could explore,” Prof Subramaniam said.

Indian science was always on his mind. He constantly threw out ideas and challenges to fellow scientists, and despite his towering stature, remained approachable to the very end—always ready to go the extra mile in support of the subject.

Professor Yashwant Gupta, Centre Director of the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA), said Kasturirangan offered key insights and suggestions that helped steer the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project forward.

Recalling one memorable challenge, Gupta said, “Dr Kasturirangan was aware of the science done using the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope in Pune. He once challenged me to explore the idea of pursuing radio astronomy from the moon and space.”

His warmth touched everyone around him, and Kasturirangan was a father figure to many.

Prof. Subramaniam fondly recalled a personal letter signed by him when she was awarded the Rashtriya Vigyan Puraskar in 2024. “It was an amazing feeling to receive that letter last August. He always acknowledged people and gave them due credit for their contributions,” she said.

When entrusted with formulating the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, Kasturirangan travelled across the country for months, engaging with educationists, university officials and academicians. For, he wanted to draft a policy that would go on to change the way knowledge was being imparted — moving beyond rote learning or stream-wise distribution of subjects and specialisations that had long defined higher education in India.