Lebo Randhari sold 56 quintals of paddy from his four-acre field at Gobardhanguda in Nabarangpur’s Kosagumuda block last year, fetching him Rs 76,160 at the government’s minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 1,360 per quintal.

This farmer from the adivasi Bhatra community is a beneficiary of probably the only state-run programme that really works in India’s poorest district.

For Randhari, the benefits flow two ways. The first is as a producer, where the Odisha government guarantees purchase of 14 quintals of paddy per acre — out of his average 18-20 quintals yield — at the MSP. Secondly, as a consumer, he gets 25 kg of rice every month at Rs 1/kg through the public distribution system (PDS). This hugely subsidised rice — 300 kg annually, equivalent to 4.5 quintals of paddy — supplies roughly half his five-member family’s 50-55 kg monthly consumption. The balance requirement he meets from his own farm’s paddy not sold to state agencies.

Story continues below this ad

Also Read | In India’s poorest district, poverty doesn’t mean hunger

Paddy storage godown at Badamada in Nabrangpur district of Odisha. (Express Photo by: Kameswar Rao)

Paddy storage godown at Badamada in Nabrangpur district of Odisha. (Express Photo by: Kameswar Rao)

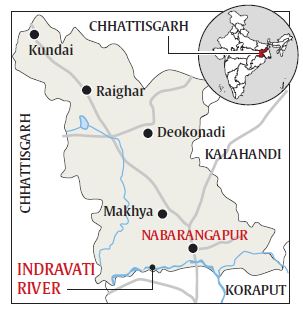

Nabarangpur is an interesting case study of a poor district that is not simply self-sufficient, but surplus, in rice. In 2014-15, its estimated production, at 3.71 lakh tonnes (lt), was twice the requirement of 1.9 lt, taking a daily consumption of 400 grams per adult for a population of 13 lakh. The latter, however, also includes children whose requirement is lower.

Being surplus has, in turn, allowed for instituting a system of procuring paddy from within the district and selling it back as milled rice to Nabarangpur’s people. Of course, there is a cost to procuring paddy at Rs 1,360 per 100 kg, milling it and selling 66-67 kg of rice that is recovered at Re 1/kg through PDS outlets. But to extent procurement and distribution operations are confined to Nabarangpur, there are savings in transport, storage, interest and other logistics costs.

During 2014-15 (October-September), 1.60 lt of paddy worth nearly Rs 218 crore was procured from Nabarangpur’s farmers at the declared MSP. The 1.07 lt rice from this paddy — about 29 per cent of Nabarangpur’s production — exceeded the district’s PDS requirement of 83,957 tonnes. “The 20,000 tonne-plus of surplus procured rice we are supplying to Malkangiri, Rayagada and Ganjam districts,” informs Ramesh Padhi, Nabarangpur’s civil supplies officer.

Also Read | Nabarangpur: Getting more water for fields

Story continues below this ad

Organisation of procurement is quite an elaborate affair. Randhari was one among Nabarangpur’s 23,755 officially registered cultivators in 2014-15 to deliver paddy at 46 primary purchase centres affiliated to 13 LAMPS (large area multipurpose society) across the district. Randhari’s centre at Badamada, for instance, procured 29,575 quintals from 386 farmers. They included smaller growers like Randhari as well as the likes of Jogendra Swain, who farms 115 acres at Duragam village and supplied 1,600 quintals paddy valued at Rs 21.8 lakh to the Badamada centre last year.

Each purchase centre has a yard where farmers bring their paddy, besides electronic weighing machines, quality-testing equipment (moisture meter, mini grader, analysis kit) and polyethylene tarpaulins for covering the procured grain. The paddy bought is handed over to the designated miller against an acceptance note, certifying that the grain received is of ‘fair average quality’ (FAQ). Within 3-4 days of delivery, the farmer is issued an account payee cheque by the LAMPS concerned on behalf of the Odisha State Civil Supplies Corporation.

“There is corruption at times, when some of our grain is declared non-FAQ and we are paid for say, 97 kg, with the miller getting 3 kg free. But the system generally works well and we do get the MSP,” says Sadashiv Das, who cultivates paddy in four acres of his own and 40 acres of leased land at Daibhata village of Nandahandi block.

Nabarangpur has 73 rice mills that can together process 2 lt of paddy annually. The individual milling capacities range from 2 to 4 tonnes per hour. “We may be small (India’s largest mill at Dhuri in Punjab of KRBL Ltd has a capacity of 150 tonnes/hour), but ours is the only real industry in Nabarangpur. Farmers, too, have an assured market and MSP in paddy. This is unlike for maize, sugarcane or tamarind where there are no mills or processing plants nearby,” notes Naditoka Mohan Rao of Sri Gupteswariamma Industries. The millers are mainly Telugu Komati Vysyas (about two-thirds), followed by Odiyas (25 per cent) and Marwaris (10 per cent).

Story continues below this ad

Paddy farmers are, moreover, entitled to crop loans of up to Rs 17,100 per acre, including Rs 7,100 in the form of fertiliser and seed sold by the LAMPS outlet and Rs 10,000 as cash component to pay for labour, diesel and other charges. These loans, attracting 2 per cent annual interest and available only for paddy cultivation, are made during May-September and repayable the following March. The Kosagumuda LAMPS, to which Randhari’s Badamada centre is attached, has alone disbursed Rs 11.38 crore of cash and in-kind credit this kharif season. These funds it has sourced from the Koraput Central Cooperative Bank, with the interest subvention enabling farmers to borrow at 2 per cent coming from the state government.

The district administration’s current focus is on introducing a Paddy Procurement Automation System or PPAS, which aims at online registration of all farmers with their village name and land particulars (plot/khata number, holding size, irrigation status, etc). These will be linked to their bank accounts.

“The idea is to transfer the procurement payments directly into their accounts, instead of the farmers having to go to the LAMPS for collecting the cheques. We implemented PPAS in one block (Nabarangpur) in 2014-15 and are extending it to six more (Kosagumuda, Nandahandi, Umerkote, Jharigam, Chandahandi and Raighar) this season. By 2016-17, even the remaining three blocks (Tentulikhunti, Papadahandi and Dabugam) will be covered,” claims Padhi.

Also, plans are underway for expanding storage capacities to accommodate the surplus rice, expected to go up with rising procurement. Currently, there are two godowns of 10,000 tonnes capacity each of Food Corporation of India and Central Warehousing Corporation and a 4,500-tonne facility of Odisha State Warehousing Corporation in Nabarangpur. The latter also has a 2,700 tonne godown at Umerkote and 500 tonnes at Raighar.

Story continues below this ad

“Our total storage capacity is 27,700 tonnes now. We are also creating a 5,000 tonne facility at Umerkote and another of 2,500 tonnes in Jharigham. Both these are under the Private Entrepreneurs Guarantee scheme (providing assured grain storage for 10 years to the investor, selected based on competitive bidding) and will be functional from the new procurement season beginning December,” adds Padhi.

A farmer in his paddy field. (Source: Express photo by Kameswar Rao)

A farmer in his paddy field. (Source: Express photo by Kameswar Rao)

Paddy storage godown at Badamada in Nabrangpur district of Odisha. (Express Photo by: Kameswar Rao)

Paddy storage godown at Badamada in Nabrangpur district of Odisha. (Express Photo by: Kameswar Rao)