Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Where the wild things are: A day in the life of Sagar Manjariya, a wildlife tracker in Gir forest

There are 160 wildlife trackers in Gir and other protected areas where lions roam. Of them, 18 are attached to the Sasan wildlife division alone.

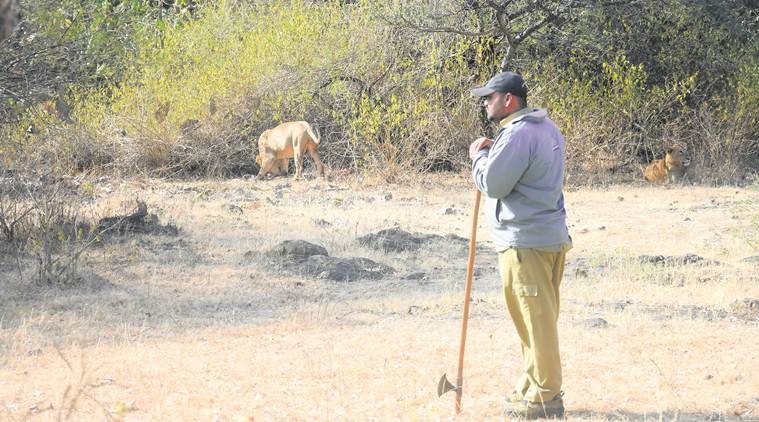

Manjariya says Asiatic lions are usually not dangerous. Armed with an axe, his job involves rescuing animals and tracking their movement. (Ashwin Sadhu)

Manjariya says Asiatic lions are usually not dangerous. Armed with an axe, his job involves rescuing animals and tracking their movement. (Ashwin Sadhu)

At 6 am on a cold winter day, Sagar Manjariya emerges from his quarters in Forest Colony in Sasan, a tourist hub from where lion safaris take off for Gir forest, in Junagadh district of Gujarat. Riding a motorbike, he reaches a roadside tea stall where fellow tracker Naresh Vaghela joins him. The duo quickly gulp tea and head into the Gir National Park and Sanctuary.

There are 160 wildlife trackers in Gir and other protected areas where lions roam. Of them, 18 are attached to the Sasan wildlife division alone. Engaged on 11-month contracts by the Gujarat State Lion Conservation Society, a trust formed by the state government, they keep a watch on Gir’s animals, especially the Asiatic lion.

The only equipment the trackers carry are torches and axes, also used by them to cut their way through thickets. On November 29, two lions had killed a caretaker, Rajnish Keshwala, and left two injured near Sasan — a fact that weighs on Manjariya’s mind.

Manjariya and Vaghela have been riding for 4 km when Manjariya hears the alarm call of a spotted dear near the bank of Raydi river. As it is still dark, he pulls out his torch to try and spot pugmarks, but doesn’t find any. The deer could have been scared by the smell of a lion, the 34-year-old mumbles.

The sun is still not up when they reach a natural watering hole. By now their walkie-talkies are buzzing, with the other trackers fanned out across the forest, in teams of six, sharing information on the animals they have spotted, and relaying it to the Control Room. One of the men in Manjariya’s team, Suresh Shekhva, says he has found pugmarks suggesting the lions have moved east.

At a forest post in Kerambha, Manjariya finally gets lucky, and in the brightening light, sees some lion pugmarks on a forest path. He marks them with the handle of his axe, so that other trackers know someone has already been there. He follows the pugmarks for around 2 km till Gangajaliya Ness, one of the 50-odd colonies of Maldharis inside Gir. A community of cattle-herders, they have lived here for centuries. The Maldharis tell him they heard the roar of two lions that morning.

It’s around 8 am that, alerted by Shekhva again, Manjariya and Vaghela finally spot a male lion, named Bahubali, who is sitting next to a rivulet. For the next 40 minutes, from around 15 metres away, the three trackers observe the lion. Manjariya notes that it appears to be well fed, seeing his “roundish belly”, and likely to rest there for some time.

The son of a Gujarat Police assistant sub-inspector, Manjariya dropped out of school after Class 10. After a couple of years of taking tourists on safaris, he became a tracker in 2009, and now earns Rs 12,500 a month.

The recent incident in Devaliya safari park was a reminder of the risks involved in the job, Manjariya says. “I was part of the team that recovered Keshwala’s body.” He points out that the lions in the safari park are zoo-bred ones. “Wild lions generally do not behave in that manner. But there is risk.”

A tracker’s job also involves rescuing animals if they are sick or injured, and helping in their medical care. They are not entitled to weekly offs or long paid leave. Manjariya says he could get four days off when his father died two months ago. Last month, he was part of the team that rescued a leopard from the Secretariat in Gandhinagar.

Manjariya and Vaghela now come across a tracker who seeks Manjariya’s opinion regarding two sub-adult male lions who have preyed on a nilgai. Manjariya concludes that the two seem fine.

As he heads back, he receives a message to submit three copies of his passport-size

photographs to get a duty pass made for the proposed visit of President Ramnath Kovind later this month. Manjariya does that before finally heading to his two-bedroom quarters around noon. As he plays with his two-month-old son, wife Uma prepares lunch. Their six-year-old daughter is at school.

By 3 pm, Manjariya is back in the forest and he and Vagela run into a tourist gypsy, which has halted to let people watch a spotted deer. Manjariya sees a biscuit wrapper on the ground and instructs a labourer to clear it. “Guides are supposed to prevent tourists from littering,” he says.

Heading back to the spot where they had seen the lion in the morning, they meet up with Irfan Bloch, another tracker of their team, and notice the scat of a leopard. “The hair in the scat suggests the leopard ate a spotted deer,” remarks Bloch.

Suddenly, looking up, Manjariya exclaims, “Here she is!” Finally, after a day of searching, they have found their lioness, who stands just 20 metres away. As the three make “Ouhoon, hoon” calls, the lioness walks closer, looking at them intently, then abruptly sits and turns away.

Manjariya says they made the “Kukavo” call. “We informed her that it was us. We believe lions know our calls.” They are in little danger from the lioness, he adds. “Unless provoked, Asiatic lions never attack humans. But they can be aggressive when they have small cubs or are in mating season.”

The lioness, whom they observe for around 30 minutes, is Sundari, identifiable by the cut in her left ear. As she continues to look the other way, Manjariya requests Bloch to hit a plant with the handle of his axe while he himself crushes dry leaves. Responding to the sound, the lioness turns, and Manjariya is satisfied. “She seems alright,” he declares.

Moving away, Manjariya informs the Control Room about the lioness. Finally, around 5 pm, he decides to head home.

He has gone hardly a kilometre when he runs into tourists clicking photographs of Sundari, who appears to be enjoying the attention. “She must have come out for some evening breeze,” smiles Manjariya, instructing the guides to not stall at one place for long.

By the time he gets home, it’s 7 pm. Manjariya’s daughter comes running out. Holding her hand, he talks about how his mother, who lives in Junagadh, worries about him. “I tell her I don’t work with wild animals. But sometimes, my name is in newspapers.”

Wife Uma refers to the November 29 incident. “I was calling him frantically, and broke down when he returned home. Now I am tense all the time he is in the forest.”

Sasan DCF Mohan Ram admits the importance of wildlife trackers for forest management. “They keep track of wild animals and also tourist movement. Without them, we can’t function.” However, says Dushyant Vasavada, Chief Conservator of Forests, Junagadh Wildlife Circle, regularisation of their services is beyond his powers. “The state government has to take a call.”

At present, Manjariya says, he goes through days of uncertainty every 10 months. Turning in around 9.30 pm, he

adds, “Sometimes I lie awake at night worrying about how I will provide for my family. But in the morning, I am back in the forest, among the lions, and I forget all worries.”

In the distance can be heard alarm calls of a spotted dear and a peacock.