‘They will send us back’: Fear of deportation spurs rush to BJP MLA’s ‘CAA enlisting camp’ in Nadia

Applicants must provide documents proving origin in Bangladesh and residence in India, and a character certificate from a neighbour

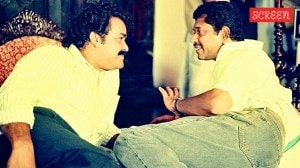

BJP MLA Asim Sarkar assists people in filling their CAA applications at his residence in Palpara, Nadia (Express/Partha Paul)

BJP MLA Asim Sarkar assists people in filling their CAA applications at his residence in Palpara, Nadia (Express/Partha Paul)Around 45 km from the Petrapol border, people are queuing at Palpara to seek help applying for citizenship under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), many saying they fear deportation to Bangladesh if they do not register.

BJP MLA Asim Sarkar has converted part of his Palpara residence into a CAA camp, where party volunteers receive forms and help applicants compile documents.

Sarkar said camps operate across his five mandals but so far only about 400 people have filed applications. At the makeshift centre he fields questions, checks paperwork and oversees volunteers who verify the identity proofs and other papers brought by applicants.

Among those at the camp was 50-year-old Milan Roy, who says he fled Patenga in Bangladesh after facing persecution.

“I have come to find out how to apply for CAA. I was told by a relative that the Indian government is granting citizenship to those persecuted Hindus who have come from Bangladesh due to atrocities,” Roy told The Indian Express.

He said he paid a middleman to cross the border and has stayed with relatives in West Bengal since. “For over a year I have not seen my family. I had come to this country to save my life but I have ended up in more trouble now. Over here also I am not getting proper jobs. There is no steady income but now I am hopeful that if I get the citizenship then at least I will get some job and will be able to bring my family to India.”

The camp also drew longtime residents who say they migrated decades ago but now fear being classed as “illegal.” Ram Chandra Guin, 55, who says he entered India in 1998 with his then-17-year-old wife and one-year-old son, said he has built a life in India, a shop, a house, voter identity documents, and now seeks official recognition.

“I am applying for CAA now because I heard that the government will push back all who have come from Bangladesh. We have seen on TV that many people from Delhi have been sent back to Bangladesh and over there they are in Bangladesh prison so I am applying now,” Guin said. He added that earlier he had avoided applying for fear of being marked an illegal infiltrator: “Previously we were told that like in Assam the Bangladeshi are sent to detention camps; we will also be sent. But then we found out that this is not true.”

Sitting outside Sarkar’s office, a young couple in their early 30s with a two-year-old son, who asked for anonymity, said they arrived on student visas in 2021 but now regard the move as permanent. Hailing from Khulna, they said the family remained in Bangladesh but “we are not safe there anymore, my son will not be safe there. We have a passport and visa but the day we left we knew it was a one-way trip, we will never go back again.”

At the camp, volunteers hand out the CAA application form and help fill required fields: applicant’s name, parents’ names, spouse and children details, profession, year and place of entry into India, current Indian address and mobile number.

Applicants must provide documents proving origin in Bangladesh and residence in India, and a character certificate from a neighbour. If a spouse is an Indian citizen, a passport copy must be submitted. Sarkar said volunteers also advise on what supplementary papers are acceptable and help those who struggle to complete the paperwork.

Speaking to The Indian Express, Sarkar, who is the BJP refugee cell’s state convenor, said the outreach was both humanitarian and corrective. “From 2000 to 31 Dec 2024 those whose names are not there we are convincing them to apply for the citizenship certificate. Our state CM has misled the persecuted Hindu refugees not to apply in CAA. CAA is for the Hindus. It is a Laxman Rekha,” he said.

He added that his Haringhata constituency has run similar camps for two months and that over 400 applications have been submitted across the area. “Many are coming to us to enquire about CAA and how to apply, what documents are required,” he said.

Local activists and some residents said the rush to apply reflects an atmosphere of fear stoked by media reports and political rhetoric.

Party sources maintain the drive will consolidate support among communities such as the Matua and other Hindu refugees who migrated before 2024; Sarkar said the exercise will also help identify “dead or fake voters” and alleged “illegal” entries to electoral rolls, claims that are politically contested.

The CAA application process involves scrutiny by government authorities and documentation requirements that can be hard to meet for those who fled years ago without records.

Sarkar acknowledged the paperwork challenges: many applicants lack formal documents and his volunteers are helping them trace and compile whatever evidence they can provide.

Officials from the local administration were not immediately available for comment. Applicants were advised to retain receipts and follow up through official channels, and some volunteers urged caution, reminding applicants that formal procedures and verification by central authorities would ultimately determine eligibility.

For those queuing at Palpara, however, the immediate imperative is clear: amid reports of detentions and deportations elsewhere, many see CAA as a possible shield against an uncertain future. “I do not wish to go back to Bangladesh as I have nothing there and I want to live here only with my family. I just have one request to this government: we want to stay here, we should get citizenship of this country,” Guin said.