Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

The Philosopher’s Muse

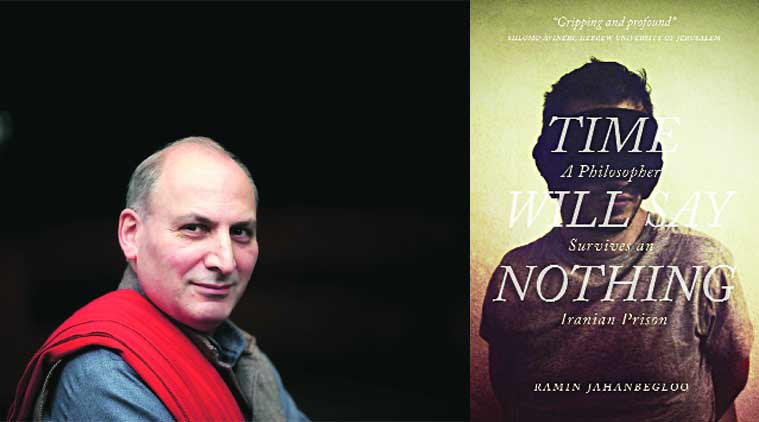

In his latest book, author Ramin Jahanbegloo confronts his own thoughts after four months in Iranian prison.

Being a political thinker and lecturing about modern capitalist societies comes easy to Ramin Jahanbegloo. But his experience of being a political prisoner in Evin Prison, one of Iran’s notorious jails, forced him to do something new: talk about himself. “I never knew I had the ability to write an entire book about my experiences,” says the Iranian philosopher, academician and author, while sitting at the front lawns of the India International Centre on Saturday afternoon.

Being a political thinker and lecturing about modern capitalist societies comes easy to Ramin Jahanbegloo. But his experience of being a political prisoner in Evin Prison, one of Iran’s notorious jails, forced him to do something new: talk about himself. “I never knew I had the ability to write an entire book about my experiences,” says the Iranian philosopher, academician and author, while sitting at the front lawns of the India International Centre on Saturday afternoon.

“I never knew I had the ability to write an entire book about my experiences,” says the Iranian philosopher, academician and author, while sitting at the front lawns of the India International Centre on Saturday afternoon.

He held a reading of his autobiography, Time Will Say Nothing: A Philosopher Survives an Iranian Prison (University of Regina Press), the previous day in the city. It documents the time he spent as a political prisoner in Evin prison. What starts like any political thriller with anecdotes from his prison life, soon becomes a flashback of memories from childhood, his time in France and India (he has spent 25 years here), his romantic liaisons, with the Iranian political scene in the backdrop. Jahanbegloo refers to a climate of uncertainty in Iran, under the then Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who was cracking down on dissent among intellectuals.

What starts like any political thriller with anecdotes from his prison life, soon becomes a flashback of memories from childhood, his time in France and India (he has spent 25 years here), his romantic liaisons, with the Iranian political scene in the backdrop. Jahanbegloo refers to a climate of uncertainty in Iran, under the then Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who was cracking down on dissent among intellectuals.

On April 27, 2006, Jahanbegloo was about to board a flight to Brussels for an international conference when Iranian authorities blindfolded him at Tehran airport and took him away. Without any reason, Jahanbegloo was held for four months in his “new home”, a 3 x 3 m isolated cell, in the political section, with only roaches for company. With lights kept on day and night, he was not allowed to move outside. His only interactions were with interrogators, who quizzed him blindfolded. Jahanbegloo turned to philosophy to maintain his sanity. “The best way to resist was

“The best way to resist was intellectually. High security prisons are made to deconstruct your mind and make you realise what you think is wrong,” says the 59-year-old scholar, who started noting down his thoughts on the back of biscuit wrappers that he purchased from prison kiosks. “These were more like aphorisms. I had a limited intellectual space to work in. So I tried to make the most of it,”he says.

For the first 50 days of his stay in prison, Jahanbegloo had limited access to books, except for the Quran (which he read five times over). Gradually, his wife was allowed visits, and Jahanbegloo was introduced to Gandhi, Nehru and Maulana Azad’s biographies, and German philosopher Hegel’s work.

“Philosophy helped me greatly; it took my mind off reality. I was not only reading it but also pronouncing these abstract concepts out loud as if he (Hegel) was joining me in the cell. I tried not to make many judgements about Iranian prisons and prison life in my book, though I touched about the political context of Iran briefly,” he says. By the end of his prison term, Jahanbegloo had over 2,000 aphorisms. He published a work in Persian, titled A Mind in Winter in 2007, which documented some of these anecdotes.

What distinguishes Jahanbegloo’s work from other prison memoirs by Iranian political prisoners such as Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari’s Then They Came for Me (2011), which was later adapted into a film by Jon Stewart, and academician Haleh Esfandiari’s My Prison, My Home: One Woman’s Story of Captivity in Iran (2009), is his style. “I am more philosophical in my writing. I cannot think any other way,” he says.

Jahanbegloo has over 30 books to his credit, including one on the Gandhian philosophy of non-violence, Conversation Series with Indian intellectuals such as Ashis Nandy and Bhikhu Parekh, and a series on architecture with Raj Rewal. In 2009, he received a Peace Prize from the United Nations Association in Spain, for promoting non-violence. “I have been trying to find an answer to what got me into prison in the first place. May be it was my intellectual outlook and my questioning nature,” says Jahanbegloo, who does not regret his prison term, but “credits it for making him a more critical and blunt person.”

Ever since his release, he has been living in exile in Toronto, Canada, where he is a professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at York University. “I realised Canada considers itself a safe haven. At the same time they do not want to criticise themselves. Living there has made me a radical thinker just like the Canadians, but at the same time I have learnt to never stop questioning,” says Jahanbegloo.

He will release his next Conversation Series with Indian academics, Richard Sorabji and Romila Thapar in May and December, respectively, this year.