‘Some Class 8 and 9 students can’t read letters’: Delhi govt launches new education mission, runs into old hurdles

The Delhi govt launched its ambitious NIPUN Sankalp Mission 2025-26 on September 5 this year, which promises Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) for every child from Classes 1 to 8.

This school-level assessment by its teachers was carried out well before the Delhi government launched its ambitious NIPUN Sankalp Mission 2025-26 on September 5 this year — a programme that promises Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) for every child from Classes 1 to 8.

This school-level assessment by its teachers was carried out well before the Delhi government launched its ambitious NIPUN Sankalp Mission 2025-26 on September 5 this year — a programme that promises Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) for every child from Classes 1 to 8.At a Delhi government school in Central Delhi, a baseline assessment recently identified 34 students from middle-school sections who were unable to read letters and words at their class-appropriate levels.

This school-level assessment by its teachers was carried out well before the Delhi government launched its ambitious NIPUN Sankalp Mission 2025-26 on September 5 this year — a programme that promises Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) for every child from Classes 1 to 8.

But in classrooms, where students have gone through several similar assessments — from Mission Chunauti to Mission Buniyaad and PARAKH Rashtriya Sarvekshan — and weak areas have been identified, learning gaps remain. The fundamental challenges of absenteeism, low parental involvement, and limited support for first-generation learners also keep surfacing.

The school’s principal said, “We hold special classes for them in the mornings. These identified students are mainly the same students who have very poor attendance. We have sent warning notices to parents as per norms, but the pattern has barely changed.”

Unlike earlier interventions, which were narrower in scope and time-bound, NIPUN Sankalp has been positioned as a three-year mission.

While Mission Chunauti (2016) had focused mainly on grouping and remedial classes for “non-readers” in Classes 6 to 8, Mission Buniyaad (2018) targeted literacy and numeracy in primary and upper-primary grades through summer camps and special classes to reduce failures. PARAKH surveys, meanwhile, were designed as periodic assessments to benchmark performance across schools.

In contrast, NIPUN Sankalp is an elaborate mission that links certification to the outcomes — a school can only be declared “NIPUN Certified” when at least 80% of each class achieves basic reading, writing, and math skills.

Delhi Education Minister Ashish Sood, during the launch of NIPUN Shala — an FLN creative learning centre — at Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya, Janakpuri, on Thursday, emphasised that the mission aims to ensure all Delhi government schools will be NIPUN certified within three years.

Phase 1 of the mission, conducted from June to September, included teacher capacity-building training and orientation for the baseline assessment. Phase 2, scheduled between October and December, involves conducting the baseline assessments.

The SCERT has issued strict instructions to government school teachers not to disclose students’ levels during interventions. During this phase, students will work through targeted workbooks, be continuously monitored, and participate in endline assessments.

The challenges

Back at the Central Delhi school on Friday — the last day of the assessment — five people were busy hovering over computer screens from morning, entering scores and cross-checking them with class-wise analysis sheets before uploading the data. They included school staff and DIET (District Institute of Education & Training) trainees who have been deputed for support.

Stacks of class-wise analysis sheets lay on the table, with scores and an ‘N’ for ‘not attempted’ marked.

“Not attempted has also been recorded,” one of the invigilators pointed out, adding that this was a much-needed differentiation to understand whether students lacked ability or simply chose not to engage with the test.

“Among classes 6 to 8, 40-50% of students seemed capable of understanding the questions. But at least 20-25% of the rest of the students were not attempting,” one DIET trainee observed.

The test material designed by SCERT included simple, everyday contexts with diagrams in some cases. For instance, one question was situational: a child throws chips on the street, another searches for a dustbin, and students were asked to tick the right activity.

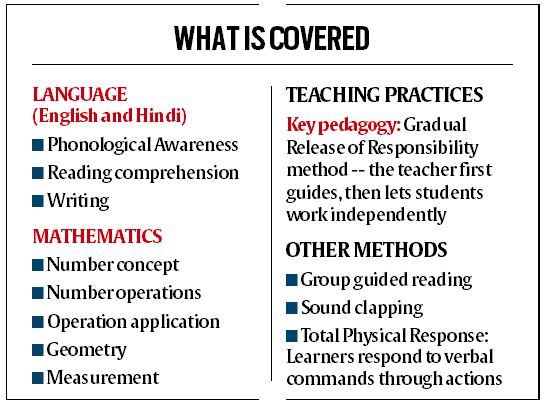

Competencies in reading comprehension, phonics, writing, number concepts, geometry, and more have been checked.

Yet, as one school head said, the effectiveness of such missions will depend less on test structures and more on student presence: “Even if we know the weak areas, if there is no attendance, then what is the point? Kaam unhi bacchon mein ho paara hai jo school aate hain (The work is happening only with those who actually come to school).”

One principal requesting anonymity said, “We are forced to promote students who would still need remedial efforts to upper classes because of the no-detention policy. This has made it difficult to get results even after such assessments… they are passed without a sense of their prior learning, which has led to complications during remedial efforts.

Educators have linked the poor performance with high absenteeism.

One of the school heads quoted above said, “Even in Class 8 or 9, there are students who cannot read letters. The availability of Special Training Centre (STC) teachers is also limited. Irregular attendance always directly impacts performance… The children are first-generation learners, and at home, nobody is literate to help them. Parents also promote long leaves for village trips.”

The divide between students who have been consistently enrolled since Class 1 and those who enter midstream has also stood out. “Students who have been in school from the start perform better. Those with non-planned admissions are much weaker. Handling both kinds of students… those at a class-appropriate level and those far below is always a challenge,” said a principal.

Earlier this month, during teachers’ training, SCERT faculty underscored that 52% of Grade 3 students in Delhi do not meet the global minimum proficiency for numeracy, while 38% perform below the minimum proficiency in literacy. “Low proficiency in reading and numeracy directly contributes to low engagement, poor self-esteem and increased dropout risk of students,” noted an SCERT document.

Parental cooperation is the most critical, one of the principals quoted above explained. “Many families ask their elder children to take care of siblings, so attendance gets affected. We have allocated three teachers to conduct special classes early in the morning, but students must also turn up.”