Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Bob, the Builder

Punk legend Sir Bob Geldof on music, life and political assassination of the arts.

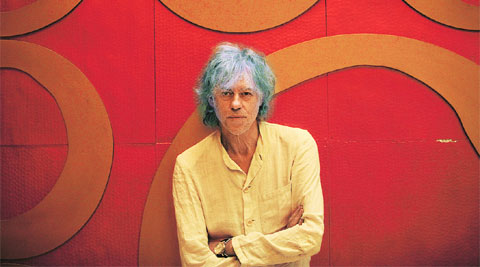

Bob Geldof.

Bob Geldof.

In the November of 1984, a warm studio in London’s Notting Hill was bustling with activity. Just after breakfast, it came alive with a Christmas song. Some of the most influential names, with some of the most ridiculous haircuts, in the history of rock music — Bono, George Michael, Robbie Williams, Chris Martin, Dido and Sugababes, among others — had come together to sing In a world of dread and fear / Where the only water flowing is the bitter sting of tears / And the Christmas bells that ring there are the clanging chimes of doom / Well tonight thank God it’s them instead of you.

This song, Do they know it’s Christmas, created after a famine in Ethiopia, remains one of the most important Christmas songs of the last century, with millions of dollars raised and donated as emergency aid. It’s been almost 30 years ever since, but punk legend Sir Bob Geldof, the man who was responsible for the song and its creation after he saw images of children dying in Africa, is finally becoming comfortable with the track. “I never thought it was a great piece of music. It was just a means to an end. I told people it doesn’t matter if it’s good or not.

You think it’s s**t, buy it. This isn’t a record that you buy for musical merit,” says Geldof, while sipping his evening espresso at Okhla’s Crowne Plaza, a few metres away from NSIC Grounds where he performed last night, bringing out a host of political anthems from his arsenal. And even now, when the grand old man of punk goes to buy lamb chops at Morrison’s Meat Counter in London, the Christmas song plays often in December. “Suddenly the butcher looks at me and goes, ‘yeah’,” says Geldof, with a laugh and many cuss words

tumble out.

It’s been years since we watched Geldof create music for a cause. The drive and passion hasn’t gone anywhere and the man still loves to lose himself in music. “I’m impelled because I do other stuff. So when I do music, there is this catharsis, this release. Every other thing you do, be it business or politics, you have to think about it in an empirical way. But with music, it’s completely the opposite. It’s intuitive. The essence of this art is in losing oneself,” he says. The musician has always wanted more stage than more fans and that’s what he thinks has “f****d the heart” of him. “You are yourself all the time. But then it’s bizarre as to how I’m more myself on the stage. That’s when the magic happens. You are exhilarated and exhausted in a good way,” says 62-year-old Geldof.

For someone who “scammed his way through gigs with his camera” to photograph bands and sell them, it was the intertwining of politics and music of the ’60s that had him come up with his band The Boomtown Rats and break all records with Rat Trap and I Don’t Like Mondays. “When you are young you are rejecting things, but here were these bands — The Stones, Dylan, The Beatles — articulating what’s happening in the world. This was the time when bands were leading a cultural change and they didn’t even know about it. Except Dylan may be; he knew. I was listening to a lot of all this,” he says.

It was one bored Wednesday afternoon at home, when a 15-year-old Geldof strummed a borrowed guitar. “And that strumming all the time, hasn’t stopped. Even now I’m watching TV and start this ‘ting ding ding’. It drives my Mrs (his partner French actor Jeanne Marine) crazy.

Now I can’t imagine not picking up the guitar and just noodle away,” says Geldof.

But it was the Band Aid and Live Aid concerts in London and Philadelphia for charity that changed everything forever; he was even called Saint Geldof. It may have scaled down his musical achievements with The Boomtown Rats, got him knighted at 34, and made him perhaps the most popular philanthropist musician all over the world. “I was f****d. My career was beginning to slide anyway. But we were known in music. I was known outside of music because I was on TV a lot, because I talk a lot. So when you do something like Live Aid, you completely move out of something you do and enter the society that engages with you. The concerts were watched by billions. I’m not Dylan or The Beatles. I’m not as talented as them. But music needed to mean more,” says Geldof, whose last album was cheekily titled How to Compose Songs That Will Sell.

Geldof’s Delhi concert, which was a part of ‘Sounds of Freedom’ organised by Sanjoy Roy of Teamwork Arts, and cancelled after Delhi Police’s denial of permission, finally happened after the High Court ruled in the organiser’s favour. “I’m glad it’s happening but this political assassination needs to stop,” he says, and many cuss words follow. “I swear a lot. I hope it’s all right,” says Geldof, in his quintessential Dublin accent that hasn’t left him despite three decades in London. “Sometimes my kids try to do the Irish accent and I ask them what the hell is that? And they joke, ‘That is exactly how you sound’,” he says.

There is a roar of laughter and suddenly Geldof goes quiet, seeming to look back, away from everything around. And just like that, Saint Bob Geldof turns into Bob the builder, the one who wants to be the change. “Rock ‘n’ roll needs to be against something. It just can’t be,” he says.