At the centre of Punjab farmer’s VRS plan, a fast growing grass he calls green gold

Bamboo plantation gains ground as low-maintenance, high-profit crop; thrives in any soil, survives drought and excess water

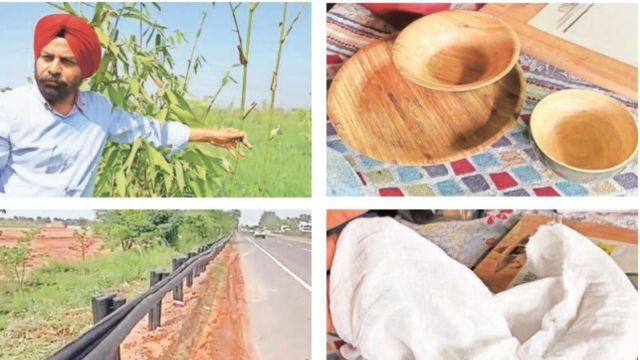

Clockwise from top: Rajveer Singh Brar shows bamboo saplings; tableware and linen made from bamboo; and crash guards made of bamboo along a road in Punjab. (Express photo)

Clockwise from top: Rajveer Singh Brar shows bamboo saplings; tableware and linen made from bamboo; and crash guards made of bamboo along a road in Punjab. (Express photo)An unplanned experiment, owing to push by a forest department officer, has — in a span of just about three years — turned into a multi-state bamboo farming enterprise spanning Assam, Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. At the centre of this enterprise is Rajveer Singh Brar (56), a progressive farmer from Rampura village in Punjab’s Fazilka.

In 2022, Brar received 200–300 bamboo saplings from the forest department for his farm in Chandigarh. They were left unplanted and died. “When the forest department officer visited again, he was disappointed, and we felt ashamed. He brought more saplings under the government’s afforestation policy and got them planted on our farm. Those plants grew well,” recalls Brar.

Encouraged, Brar experimented by planting bamboo along the boundary of his kinnow orchards in the Abohar–Fazilka area. The orchards often suffered from hot winds that scorched the fresh leaves of kinnow plants. “We could have gone for eucalyptus or poplar, but those need replanting every 5–6 years and are vulnerable to wind damage. Locally procured bamboo didn’t survive well either,” say Brar, adding that his father then asked him to study bamboo farming seriously.

This led to visits to agricultural universities and extensive travel — from Maharashtra’s Konkan belt, including the village Nee Paani (“No Water”), where bamboo cultivation thrives, to Kodal, which has extensive bamboo plantations, followed by Madhya Pradesh, and later the Northeastern states, including Nagaland and Assam, to understand the nuances of bamboo farming.

His family acquired a piece of land in Assam’s Silchar to set up a nursery. “Bamboo thrives in the Northeast. Growing our plants there helped ensure survival in Punjab and other northern states,” Brar says.

Brar experiment in bamboo farming began with a 6-acre block in Abohar. Bamboo saplings were planted along an acre of kinnow orchard. He then helped several farmers to grow these in Suratgarh, Jaipur, Bikaner, and Dausa in Rajasthan, parts of Haryana and Punjab. “It can grow on both dry and waterlogged land, depending on the variety,” he says.

“There are different propagation methods — tissue culture, seeds, and rhizomes — for preparing sapling. Our nursery in Silchar uses seeds to produce saplings. Initially, there was no profit or loss, but now we’ve built a viable business model. We provide complete assistance— from supplying saplings to guiding cultivation and post-harvest processes,” Brar adds.

Economically, bamboo offers lucrative returns — about Rs 1.5 lakh per acre in the initial years and Rs 6–8 lakh per acre annually thereafter — while requiring minimal water, no fertilisers or pesticides, and virtually no maintenance.

“Bamboo’s appeal lies in its longevity and versatility: once planted, it needs a four-year wait for the first harvest but can then be harvested every year for up to a century. It can be cultivated in any season, has a calorific value of 3,800–4,500 (higher than coal), and one quintal can yield 20 litres of ethanol,” Brar explains. “Environmentally, it’s a powerhouse — absorbing 4–5 times more carbon dioxide and releasing 35% more oxygen than most plants, while drawing moisture from the atmosphere and storing it in the soil and one can get around 100 tonnes of bamboo per hecatres per year without replanting it for a century as against 25 to 30 tonnes per hectares for other trees that need re-tranpltantion every 5-10 years”.

The initial cost is Rs 40,000–50,000 per acre, after which maintenance is minimal. “No fertilisers, no pesticides—bamboo practically grows on its own after establishment. Its roots store water and draw moisture from the atmosphere, making it ideal for areas with water scarcity,” he says.

Bamboo grows in all soil types—light, loamy, barren, or waterlogged—and can be planted at spacings of 13×5 feet or 20×20 feet plant to plant and root to row, accommodating 400–600 plants per acre. Each plant can grow 25–30 feet in just 90 days.

Brar’s joint family owns about 150 acres in Abohar, Fazilka, Ropar, Chandigarh, and Rajasthan, cultivating orchards, vegetables, cotton, paddy, wheat, sugarcane, and guar. They plan to expand bamboo cultivation to 20 acres.

Brar cultivates 10–12 varieties, including Nutan, Green Vulguris, Yellow Vulgaris , Katanga, Sandro, Bambusa Polymorpha, and Assamica etc. The tender shoots of some varieties are used to make pickles, murabbas etc. Such shoots are sold at Rs. 500 per kg. Around 1,500 products can be made from bamboo — furniture, paper, fabric, cups, plates, toothbrushes, pickles, preserves, handicrafts, charcoal, and even newspaper paper. Some varieties are as strong as iron. Beyond farming, people are opening bamboo-themed restaurants in the middle of orchards, setting up yoga and meditation retreats, and creating photo-shoot and picnic spots—showcasing the agro-tourism potential of bamboo. It is also ideal for use as a boundary wall for farms or homes.

“Bamboo is now being used in house construction as a replacement for iron or steel, saving 15–20 times in costs after proper treatment. The central government is even using it for crash barriers on highways,” Brar says.

As India moves towards green energy, bamboo is attracting attention for bioenergy. “A 15 MW thermal power plant needs about 3,000 acres of bamboo for fuel. It’s available year-round, stores easily, and earns carbon credits,” he adds.

He also compares it with paddy stubble pellets promoted by the government. “Paddy pellets have lower calorific value and are hard to store. With global environmental mandates—such as the Glasgow Pledge—discouraging premature harvesting of trees, demand for mature bamboo is likely to grow. Now that bamboo is classified as grass, you don’t need permission to cut it like trees,” he adds.

Brar’s Rampura farm on NH-7 has become a hub for farmer interactions, attracting interest from 30–35 NRIs. “I call bamboo plantation the Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS )— that’s why my firm has been named VRS Agritech — because once planted, it can generate income for five generations,” he says, adding that those who cannot spare much time for farming but have land should opt for this eco-friendly and highly profitable farming.

Bamboo is also ideal for intercropping — turmeric, ginger, wheat, vegetables, and even paddy can be grown under it during the first four years before harvest begins, and even after.

With its strength, durability, climate benefits, and wide range of uses, Brar believes bamboo could help Punjab break its dependence on wheat and paddy — ushering in both ecological and economic sustainability.

Bamboo varieties range in height from 8 to 30 metres, with diameters between 3 and 12 inches. It has a high tensile strength comparable to steel and an impermeable outer layer that protects it from water-induced rot—an issue that affects most other organic materials. It is also among the best alternatives to plastic, a major contributor to global pollution, which calls a Global Plastic Treaty.