Gujarat Hardlook: What we know of the Encephalitis Syndrome plaguing Gujarat

Among the 78 children who died of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome in Gujarat this year, only 28 were infected with Chandipura Vesiculovirus. Even as epidemiological investigations are underway, ADITI RAJA and BRENDAN DABHI report on the outbreak that has taken a huge toll on children in two months.

Pradeep Bariya and Hansa, parents of Devanshi. (Express Photo by Bhupendra Rana)

Pradeep Bariya and Hansa, parents of Devanshi. (Express Photo by Bhupendra Rana)The world turned upside down for Pradeep Bariya and his wife Hansa, residents of Kotda village in Panchmahal district’s Godhra, when their only child, four-year-old Devanshi, suddenly experienced rigor while the family was asleep in the wee hours of July 16. Within a few minutes, Devanshi began vomiting and passing loose motion and eventually lost consciousness.

The tribal couple rushed Devanshi to the local hospital that refused her admission. She was then taken to the Godhra civil hospital, from where she was referred to Vadodara’s SSG Hospital, where she was diagnosed with Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES).

“She was with us only for about 12 hours after she was admitted to the Vadodara hospital. Before we could even understand what was happening, she had left us…,” said Pradeep (23), who earns a living by farming on his 1-bigha land that separates their mud-plastered home from the motorable road in the village.

“The doctors and government officials said my daughter was affected by Chandipura virus but they have not given us a any document of the diagnosis or explained what happened all of a sudden,” he added.

His wife Hansa (25) said she has not been able to grieve the loss of her only child. “I keep hoping that it is a bad dream that I will wake up from… Since the day we admitted her to the hospital, we have been flooded with visitors – medical teams, government officials and even experts, who have collected samples of us, our animals and even captured some sand flies from the house.”

Hansa said that on July 15, the couple had taken Devanshi to Godhra to complete the formalities of getting her an Aadhaar card but a glitch interrupted the process and they returned home. “She was playful and unwillingly went to bed. She had no fever or any other symptom. What unfolded after that has left us shattered… We would have celebrated her fourth birthday on August 8,” said Pradeep.

The couple has been unable to fathom why no other children in the village had similar symptoms. A neighbour of the couple said, “If the disease spread so rapidly, how would it only affect one child? May be she had congenital problems the parents were not aware of.”

While Chandipura Vesiculovirus (CHPV) cases have historically been predominantly reported from rural areas, in Gujarat, urban areas were also impacted by AES cases this year, many of which later turned out to be CHPV.

Three-year-and-eight-month-old Dhruti Parmar, a resident of Gotri in Vadodara city, succumbed to AES after being admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit of SSG Hospital on July 18. She was the first suspected CHPV patient from the city, though her CHPV report later came back as negative.

Hitesh Parmar, father of Dhruti who died on July 18. (Express Photo by Bhupendra Rana)

Hitesh Parmar, father of Dhruti who died on July 18. (Express Photo by Bhupendra Rana)

Her father Hitesh Parmar said, “Her symptoms began after we travelled to her maternal grandparents’ home in Ankleshwar. She had a mild fever for a day but recovered. She also attended school for a day but her fever returned. We tried home remedies to alleviate her symptoms but around 4.30 am on July 16, she began vomiting and had loose motions. We rushed her to a private hospital but when she had a seizure, they referred us to SSG Hospital stating that her symptoms resembled CHPV… She was on ventilator support for two days before she passed away…”

He added that after Dhruti’s CHPV report came back negative, the hospital informed the family that she had passed away due to neurological complications and inflammation of the brain. SSG Hospital’s notes in case of Dhruti stated that she suffered “respiratory failure with nasal bleeding”, as seen in most other fatalities at the hospital.

“We live in a joint family. My brother has two children and I have a five-month old son. Since Dhruti’s death, even when the children cough or sneeze, we are petrified… Lack of information about her case has left us edgy and confused. I cannot help thinking if a mistake on our part lead to this. Our home does not even have sand flies, what could be the cause of encephalitis,” Hitesh said.

Sand flies, which breed in the monsoon, are vectors of CHPV that infects mostly children between nine months and 14 years of age.

No more health bulletins

The Gujarat government, which was putting out daily bulletins on AES and CHPV, stopped issuing the same from August 20, stating there had been no new cases.

Among the 78 children who died of AES in the state, 28 had tested positive for CHPV. The government is not clear which pathogen could have killed the rest of the children.

Responding to a question asked in the Lok Sabha by Banaskantha MP Geniben Thakor on August 9, MoS Health and Family Welfare Anupriya Patel had said that a national joint outbreak response team (NJORT) had been deployed to assist the Gujarat government in undertaking public health measures and for detailed epidemiological investigation into the AES outbreak. Experts from Integrated Disease Surveillance Program (IDSP), National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and National Institute of Virology (NIV) in Pune are part of the NJORT. The teams from NCDC, ICMR and NIV are also investigating AES and related deaths.

There are no answers yet for parents whose children died while suffering from high grade fever, convulsion and brain inflammation but tested negative for CHPV.

A senior health department official said, “GBRC (Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre) has conducted whole genome sequencing of samples from CHPV positive patients and found only one non-consequential mutation from previous strains. However, there haven’t been encouraging results in the quest to find what caused encephalitis in the children who tested negative for CHPV. A series of tests are being run at NIV and results are yet to arrive.”

Dr Chaitanya Joshi, director of GBRC, was unavailable for comment.

36% cases, deaths due to CHPV

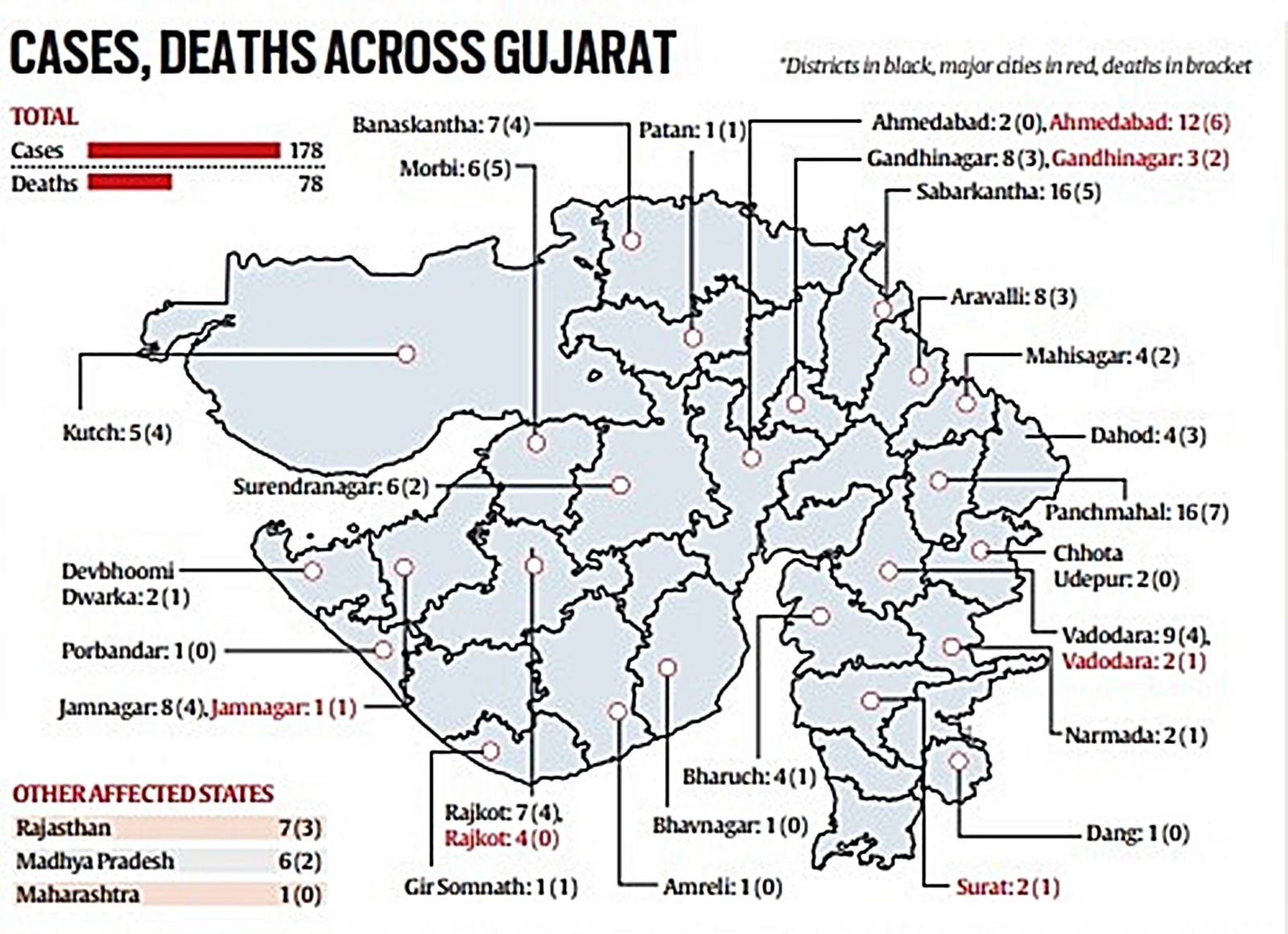

The children who died from CHPV are almost two-thirds of the total cases, which was first reported on June 27. The outbreak is spread over 26 of the 33 districts and six of the eight major cities of Gujarat. Some patients, belonging to Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, were also admitted in Gujarat.

As of August 19, with no new admissions, the AES caseload stood at 178, all children – 164 from Gujarat, seven from Rajasthan, six from Madhya Pradesh (MP) and one from Maharashtra. The toll was 78 – 73 from Gujarat, three from Rajasthan and two from MP.

Test results as of August 16 showed that of the 170 samples examined, only 62 cases or 36 per cent of the patients had CHPV. Among the 78 children who have died, only 28 or 36 per cent tested positive for CHPV.

Till Day 53 of the outbreak – August 19 – 89 patients had been discharged from hospitals while 11 remained under treatment.

The Indian Express spoke to several doctors at tertiary-level civil hospitals involved in the treatment of these children. In some cases, patients were reportedly misdiagnosed as their symptoms were similar to AES, with some also testing positive for Enterovirus and Meningitis. But in majority of the cases, doctors continue to be perplexed at what transpired in the last-month-and-a-half.

Death cases across Gujarat.

Death cases across Gujarat.

Dr Ashish Jain, head of the department of pediatrics at GMERS Himmatnagar MCH in Sabarkantha, where the outbreak was first identified on June 27, said: “The common symptoms among CHPV patients were high grade fever, vomiting, altered sensorium and convulsions within one or two days of onset, followed by multi-organ dysfunction. Other encephalitis patients also had diarrhea as a major symptom.”

“Since there is no specific anti-viral medication available, only symptomatic treatment could be given. Research is needed to find other emerging novel viruses that threaten humans,” he added. Only eight of Dr Jain’s 34 AES patients had tested positive for CHPV. Also, only two of the 11 children who died at the hospital had contracted CHPV.

Patient Zero

The patient zero in this year’s CHPV outbreak was not the first but the second child who died with symptoms associated with the virus. The first patient, a boy from Udaipur, was suspected to have contracted CHPV at GMERS Himmatnagar MCH on June 27. He died before his sample could be sent for testing.

The second child, 4-year-old Kinjal Ninama from Mota Kanthariya village in Aravalli district’s Bhiloda, who also died within hours of treatment, became the first lab-confirmed patient in Gujarat to have been infected by CHPV. However, by the time the report came in from NIV Pune, she had already died.

Precious time lost

In the first 22 days of the outbreak, till July 28, the Gujarat government received results of just seven samples from NIV. This is because the health department sent samples directly to NIV, taking days for the samples to reach and then be tested in Pune.

During this time, only Kinjal tested positive for CHPV. The other six samples tested negative, not just for CHPV, but also for Japanese Encephalitis, Enteroviruses, Flaviviruses and Herpes Simplex Virus.

It was only on July 18 that Chief Minister Bhupendra Patel decided in a Cabinet meeting that samples would be sent to GBRC where RT-PCR tests would determine whether suspected patients with AES were infected with CHPV.

This was done after the toll, according to Health Minister Rushikesh Patel, doubled from eight children on July 16 to 15 on July 17.

Red flag in urban areas

Perhaps the biggest issue plaguing doctors was that though the outbreak was initially classified as being due to CHPV, the vector responsible for infecting humans – the sand fly – was only predominant in rural eastern and central Gujarat. However, AES was reported from more than 26 districts and six major cities.

If a large number of cases are identified from a particular area, and if some test positive for CHPV, it could be considered a cluster with common treatment protocols being applied for all patients. However, in this outbreak, a senior health department functionary said there were no village clusters. All cases were from different talukas and districts, raising suspicion that a simultaneous outbreak could be in progress side-by-side with CHPV. Dr Nilam Patel, Additional Director of Public Health in Gujarat, remained unavailable for comment.

At present, while the outbreak has been contained, researchers continue to search for answers, not just in the interest of science and public health, but also to help give some closure to the parents who have lost their children.