At one of five tribal schools that IAS officer flagged as ‘rotten’, challenges big and small

The school is one of five schools where, after an inspection was carried out on June 13 as part of Shala Praveshotsav, IAS officer Dhaval Patel had flagged the “poor state of education”.

The project is supported by the World Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). (Express photo)

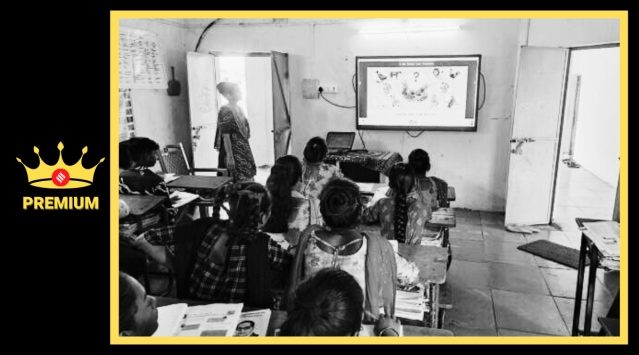

The project is supported by the World Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). (Express photo) At 9.15 on a rainy morning, at the Jamli (Dolariya) Primary School in Gujarat’s Chhota Udepur district, 28 students in Class 8 are practising writing three-digit numbers in words, and reading two- and three-letter words in Gujarati that the teacher has written on the board.

These are assignments from the Foundational Literacy and Numeracy material, which the class of eight boys and 20 girls are being made to practise to test their learning from previous classes.

Hemlataben Sutariya, who teaches Maths and Science, points to ’76’ and ’89’ on the board and asks two students to read the numbers aloud. They answer correctly. Then, she asks one of the girls to write ‘five hundred and forty’ on the board. The student first writes 5,040 and then 50,040.

“When they see someone from outside, they get nervous,” Sutariya said apologetically, as another student runs to the board and writes the correct number.

The school is one of five schools where, after an inspection was carried out on June 13 as part of Shala Praveshotsav – the government’s flagship scheme to ensure 100 per cent enrolment and which saw the participation of officers across departments – IAS officer Dhaval Patel had flagged the “rotten” and “poor state of education”.

Chhota Udepur, which was carved out of Vadodara in 2013, is one of seven new districts that still does not have a district institute of education and training (DIET). (Express photo)

Chhota Udepur, which was carved out of Vadodara in 2013, is one of seven new districts that still does not have a district institute of education and training (DIET). (Express photo)

Patel, the Commissioner of Geology and Mining, had found that children in five of the six schools he visited in the tribal district struggled with foundational learning skills.

After his visit, in a letter addressed to Education Secretary Vinod Rao and copied to the Director of Primary Education, the District Collector, the District Development Officer, the District Primary Education Officer, the Taluka Primary Education Officer, the Block Resource Centre Coordinator, the Cluster Resource Centre Coordinator and the principals of all the six government schools, he wrote, “Looking at the poor state of education at five out of six schools, my heart felt indescribable guilt. These poor tribal children do not have any other source of education. This is my strong opinion that we are doing injustice to them by giving them this rotten education. We are ensuring that they continue doing labour work generation after generation and not move forward in life. This is the height of moral decadence where we are cheating students and their parents who trust us blindly.”

Out of six taluka primary education officers positions, five are vacant, and the district has no education inspectors.

Out of six taluka primary education officers positions, five are vacant, and the district has no education inspectors.

The students tested during the inspection were randomly chosen for the assessment held in the principal’s room, teachers said.

Calls and messages sent by The Indian Express to Patel went unanswered.

On the Jamli school, he wrote, “At Jamli (Dolariya) Primary School, when I asked a girl student of Class 4 to add 15 and 14, she instead started crying, while another student gave 56 as the answer to 80-36.”

The school is among those involved in the state government’s ‘Mission Schools of Excellence’ scheme under which, over six years, the physical and digital infrastructure of schools are to be strengthened, with the investment linked to performance. Spread over six years, the scheme aims for academic excellence, imparting foundational learning and higher-order thinking skills, and new-age learning experiences. The project is supported by the World Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Yet, on the ground, schools in this largely tribal district are hobbled by several challenges – from absenteeism to a language barrier.

Chhota Udepur District Primary Education Officer (DPEO) Imran Soni said, “While the teachers need to put in additional effort in these border schools, the high rates of absenteeism among children is another reason to consider. Older children are asked to take care of their younger siblings at home when their parents are out for work. Children are also taken to farms for work by their parents.”

The high number of vacant positions in the education department, including in the posts of education inspectors, district education officers, district primary education officers and taluka primary education officers, has also been cited as one of the reasons for the lack of monitoring of these schools.

Chhota Udepur, which was carved out of Vadodara in 2013, is one of seven new districts that still does not have a district institute of education and training (DIET). Out of six taluka primary education officers positions, five are vacant, and the district has no education inspectors.

During the recent special enrollment drive, four boys were enrolled in Class 1, taking the total number of students in the school to 222 – 104 boys and 118 girls. The school employs eight teachers.

Principal Manishkumar Rathod pointed out that while girls outnumber boys now, in 1959, when the school was established, it had no girl students.

Despite these advances, teachers say they face practical difficulties.

More than four weeks since the new academic session began on June 5, heavy rain has delayed the day’s class, which usually starts at 7 am, by two hours.

Getting to school is tough in these parts. In 2013, The Indian Express had reported how students of some villages in this district swam through a river to go to school.

Irregular attendance is a nagging issue as parents migrate to other districts for work, the principal said, adding that children whose grandparents stay back in the village usually manage to attend regularly. On an average, attendance in the school is around 40-50 per cent. On rare occasions, the attendance may go as high as 80 per cent, teachers said.

Principal Rathod said that while two of the students, from Classes 5 and 8, whose cases were cited but not mentioned by name in Patel’s June 16 letter to the Education Secretary, had moved to their maternal uncles’ home in nearby Wadhwan village, a Class 4 girl, also mentioned in the letter, had refused to attend school for more than a week until teachers persuaded her to come to school.

“To ensure children attend school regularly, we have to keep visiting their homes, especially at the beginning of the session,” the principal said.

Another barrier for both teachers and students is language. While Gujarati is the medium of instruction in government schools such as the one in Jamli, many of the students speak tribal dialects linked to the Rathvi language. Most of the teachers at the school, however, are not from Chhota Udepur district – four are from Mahisagar, and three others are from Surat, Khera and Amreli.

“It took us some time to get used to their language. Now, every year, when the new batch comes, we have to first make them learn basic Gujarati words,” a teacher said, explaining why the students could not understand some of the questions the bureaucrat asked during the Praveshotsav.

“For instance”, she said, “in the tribal dialects, hair is nimala, slipper is chatiya, buffalo is dobu, near is oru, far is paru, clothes is chakhla and fire is vadher”.

The inspection during Shala Praveshotsav also led to an undertaking by teachers of the five schools to the District Primary Education Officer that they would “atone for their mistakes and ensure these shortcomings will not be seen in the future”. The undertaking by teachers of the Jamli school read, “We will donate time voluntarily, make special arrangements for the administration and the children’s studies and bring improvement in the quality of education”.

DPEO Soni said the teachers were not asked to submit such an undertaking, but did so on their own after “realising they should take responsibility”.