The staff at barrister Jivanlal Desai’s house, Jivan Nivas, would wonder why their guest — a wiry man who had returned from South Africa — spent most of his time at home, while their boss was at work.

“In a bid to end the chatter, the guest, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi told them one day, ‘I am not idle. I am thinking about how to start a war against the British’,” says Desai’s grandson Shailesh Diwan, 86, narrating an account that has passed down in the family since 1915.

According to Diwan, Desai and Gandhi had studied law together in London. On his return from South Africa, Gandhi stayed at Desai’s bungalow in the now-crowded Kalupur area which is near the railway station.

A ‘vacation home’ that became Bapu’s first ashram in India

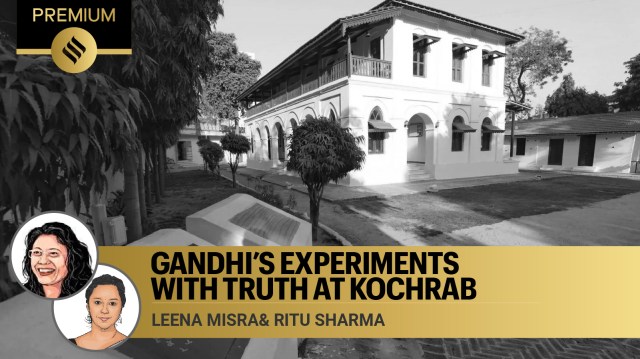

Desai later let out his “vacation home”, a European-style bungalow with a large garden, in Kochrab village, then on the outskirts of Ahmedabad on the banks of the Sabarmati river, to Gandhi. It was here that the Mahatma would start his first ashram, the Satyagraha Ashram, in India, on May 25, 1915, and begin his experiments with truth.

Diwan and his wife Gita visited the bungalow standing in a 5000-sq metre plot, on March 13 this year, to relive old memories. A day earlier, PM Narendra Modi had inaugurated the renovated Kochrab ashram virtually, while laying the foundation of the Gandhi Ashram Memorial and Precinct Development Project in Ahmedabad’s Gandhi ashram.

“Since both did not believe in freebies, my grandfather and Gandhi decided on annual rent — Re 1 — for the Kochrab house,” says Diwan, who has recently moved to Ahmedabad from Mumbai.

A plaque on the bungalow’s wall says Morarji Desai, then the Chief Minister of Bombay who would later become the Prime Minister, declared the “historic and pure” ashram in Kochrab a memorial on October 4, 1953, five years after Gandhi’s assassination. In 1954, while Morarji Desai was the Chancellor of Gujarat Vidyapith, the varsity founded by Gandhi in Ahmedabad, the ashram’s management was handed over to the Vidyapith, though its ownership remained with the state.

The two-storey building’s thick walls plastered with limestone and the wooden ceiling resting on varnished logs offer much-needed respite from the blazing Ahmedabad sun. During a tour, Bhim Bahadur, 44, the caretaker of 22 years, unlocks the aged but strong iron latches on each of the solid wood doors to the rooms and flips the antique black switches, each of them working.

The ground floor, surrounded by a verandah, has rooms used by Gandhi, Kasturba, the other inmates and for storage. A wooden staircase leads to the top floor, which has a low-seating conference room and a library with wooden flooring. While the ground floor has bathrooms, the first floor has a spacious balcony.

Bahadur says everything in the house is over 100 years old, including the wooden blinds on doors. A heavy brass bell hangs from the ornate eaves of the upstairs balcony. “This was rung to ensure everyone was up at 4 am, came down for prayers by 5.30 am, had meals on time and went to bed by 9 pm,” says Bahadur, who belongs to Nepal.

A separate single-storey building on the rear side is a kitchen, with a roof made of “imported tiles”. It also has a storeroom, toilets and bathrooms. “The small room used as a store has a large cupboard, so big that it cannot pass through the door which suggests it was built inside this room and dates back to Gandhiji’s time,” says a booklet on the ashram by Ramesh Trivedi, a retired Vidyapith teacher who looked after the ashram for over 18 years, before relocating to Canada.

Another longish building, Paanch Ordiyo (five rooms), on the premises was used for activities like weaving and carpentry. The newest addition at the Kochrab premise is an Activities Centre, built in modern design, with around 10 rooms on the top floor, including four air-conditioned ones that are named after various ashram inmates, including Dudhabhai Dafda, a Dalit weaver whose family Gandhi took into the ashram causing outrage among some inmates.

While the Diwan family is not too happy with the contrast this building poses against the original buildings, they are happy it has been restored and renovated, in an “as was” condition.

The earthquake on January 26, 2001, caused immense damage to the building. Trivedi was posted at the ashram around that time by the then Vidyapith Vice-Chancellor. He took charge of the repairs with government funds, including replacing the broken Kota stone floor in Gandhi’s room with a mirror-polished version.

“We are happy that nothing has changed in the building after the latest renovation. Otherwise, what is the point?” says Diwan.

When Gandhi would stopped by for a chat

Historian Rizwan Kadri, who lives in his ancestral home at Kagdiwad, a stone’s throw from the ashram, is among those who pushed the authorities for the upkeep of the ashram. He says his grandfather Nooruddin Kadri came to Kochrab, which lies on the west bank of the Sabarmati, in 1910 from Raikhad, on the east bank, “to get away from the crowd”. The family came to be known as the ‘Bootwala family’ since they owned the Gujarat Boothouse.

Kadri says, “On the way to the Sabarmati river, Gandhi would often stop by at our house to chat with my grandfather.”

Mahatma-ni Parikrama (The path of the Mahatma), a book Kadri wrote, inspired by notes from Gandhi’s diary that are preserved at the National Gandhi Museum in Delhi, has details of how Gandhi and Kasturba did a vastu puja at the Kochrab Ashram on May 20, 1915, before moving in. On the ashram’s centenary, Kadri had organised an event, along with the Swaminarayan Gadi Sansthan, Maninagar, to release his book on Gandhi and Lokmanya Tilak.

Over the years, however, the Kochrab ashram became a victim of neglect. “Luxury buses would remain parked outside, creating a mess, even as the ashram would remain mostly closed,” says Kadri.

At least 15-30 feet of the ashram’s front space was taken for the expansion of Ashram Road, an arterial road in Ahmedabad, in lieu of compensatory land on the rear side.

Showing pictures of the decorated ashram on March 12, 2024, which also marked the 94th anniversary of the Dandi March, after PM Modi inaugurated it virtually, Bahadur told The Indian Express, “Iss mitti ko aap sar par rakkho. Jo kaam tay kiya hai, woh zaroor hoga. Utna power hai iss jagah ka (pick up the earth here and place it on your head. Whatever task you have set out to achieve, will be successful. Such is the power of this place).”

“Earlier he (PM) was to come here, but he inaugurated it digitally. Maybe because the ashram is in a crowded part of the city and would have inconvenienced people,” he rues.

A series of wall panels quoting from his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, tell the story of the ashram under Gandhi. A panel states how many friends convinced Gandhi to choose Ahmedabad over Haridwar and Rajkot where he did his schooling.

Kadri’s book says it was Ahmedabad-based Dr Hariprasad Desai among those who convinced Gandhi to choose the city during the Mahatma’s first visit to Ahmedabad in January 1915.

“I had a predilection for Ahmedabad. Being a Gujarati, I thought I should be able to render greatest service to the country through the Gujarati language. And then, as Ahmedabad was an ancient centre of handloom weaving, it was likely to be the most favourable field for the revival of the cottage industry of hand spinning. There was also the hope that the city being the capital of Gujarat monetary help from its wealthy citizens would be more available here than elsewhere,” Gandhi writes in his autobiography.

The panels also clarify why he chose the name Satyagraha Ashram instead of ‘Sevashram’ or ‘Tapovan’, as suggested by others. His autobiography explains, “…I wanted to acquaint India with the method I had tried in South Africa, and I desired to test in India the extent to which its application might be possible so the name Satyagraha Ashram to convey goal and method of service”.

According to Kadri’s book, when Gandhi decided to settle in Ahmedabad, “he transformed the ashram into an antithesis of everything Ahmedabad stood for in those days. Here was a city of moneyed mill owners who lived a life of opulence. In stark contrast, the Satyagraha Ashram at Kochrab was defined by austerity”.

The ashram started with 25 men and women, 13 of them Tamilians, who had accompanied Gandhi back from South Africa. The ashram took in children as young as four years old, with their parents’ consent. The strength grew to about 100 inmates, including Vinoba Bhave and Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar, an activist from the freedom movement, in the two years that Gandhi occupied it.

A Dalit family comes to the ashram

On September 11, 1915, in a hit on untouchability — which he considered a “blot” on the country — Gandhi took Dudhabhai, a Dalit weaver and his family, into the ashram. Initially, there were vehement protests by the inmates, including Kasturba.

“This upset a neighbouring community and even Vaishnav businessmen refused to fund Gandhiji’s activities. Bapu (Gandhiji) told the ashram inmates that if a boycott was declared and they were left without funds, they would shift to the untouchable’s colony. One morning, a wealthy businessman from Ahmedabad anonymously donated Rs 13,000 to the ashram,” writes Kadri, adding that many believe the benefactor was textile baron Ambalal Sarabhai.

Kadri co-relates dates from Gandhi’s diary, where a note on September 17, 1915, states that “Ambalal Sheth came today”. Gandhi also started an ‘Antyaj Ratri Shala’ for Dalits at the ashram, besides encouraging the inmates to practise celibacy, do physical labour and wear swadeshi.

In June 1917, when plague hit the city, Gandhi shifted the ashram to Sabarmati, some 8 km away. In Sabarmati, he founded the Harijan Ashram, now popular as the Gandhi ashram.

Although Diwan does not have any historic documents on the exchange between his grandfather and Gandhi, the extended Desai family, spread between Ahmedabad and the US, often gets together at Kochrab for family photographs.

They are also happy to have the permission to “host some family events there some times, while maintaining the sanctity of the place, without band-baja,” says Gita Diwan.