Angry Young Writers: Chhapak writer Atika Chohan on why Bollywood screenwriters still get the wrong end of the stick

Screenwriters carry us to incalculable destinations — from blank pages to unforgettable characters, giving words to emotions, turning blockbusters into classics. Screenwriter Atika Chohan turns the spotlight on her kind.

Almost every day, the film industry explains things to me. A screenwriter creates a blueprint like an architect enlisted for an unbuilt house; an architect never claims to live in the home she designs. The memo is to be passionate in execution but detached from ownership — a surrogacy with no claims on genes. The rare event that a director or a producer attributes the similarities of the film’s ethos or style to the writer’s, is still an aberration. Not a norm. Please don’t get used to it. The house is not yours to live in. The baby is not yours to soothe. The eventual credit is an accident of the contract. Seeking anything more likens you to being an upstart.

The film industry explains to me further why it is rude to seek a sense of belonging on creations servicing directors. “Did you come up with the original idea?” But that was one line. “Did you buy the life rights?” But the subject doesn’t know me as a famous person. “Did you get the actor?” Arre, but you don’t let me come on the sets precisely because I will acquaint myself with the actor.

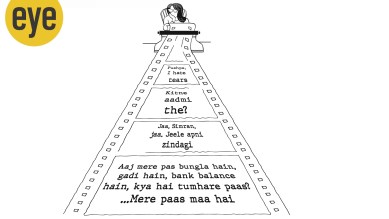

Screenwriting is still a technical award category in India; we are a zero-sum game against the creative careers of our directors. And this is how I fared that evening — half-licked by the world’s ways, bracing to tolerate more evil — when I saw the documentary, Angry Young Men, on the legendary screenwriter duo of the ’70s, the masters Salim-Javed (directed by Namrata Rao). A slick quip by Javed Akhtar sees him recap the underlying jibe that sought to cut the writers back to their size. “Writer ho, phir bhi chahte ho ki sab tumhe jaane (You are a writer and expect that people should know you?)”

Ideally, the colonial entitlement underlying the query should have made the screenwriters of 2024 gasp with wonder. Invisiblising the writer should have been a thing of the ancient past, right? Sadly, the piercing line made many of my lot hard-relate to the primitive feudalism of the credit system still pervading the power hierarchies of the industry. Yes, we don’t have to write our names overnight on posters put up across Mumbai, the way these two ‘brats’ (as Jaya Bachchan calls them) did!

Lately, the rising rebellion is quelled by the cosmetic granting of social media tags as the film approaches its release. But what is to be examined is that the real order of power remains in the hands of directors and producers. Nothing proves it more than the relevance of the Salim-Javed angst — to be seen beyond the permissible limits — 50 years after they were actively writing and creating.

Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar were not the first to foreground the working-class hero in the mainstream, but they birthed some of the most remarkable ones. The plots were pulp, but their plot was not what made them the golden boys of the ’70s. TS Eliot said that plot is the bone you throw the dog while you go in and rob the house. By extension of the analogy, Salim and Javed are the rogues who brought back the rubies of unforgettable characters from their deep heist. Their canvas was filled with many a bleeding heart, gun-toting boys with rancid daddy wounds, brought to reckoning by black widows and hyperbolic mothers seeking thirsty revenge. While one could grudge them the sin of making women play minor characters, I have rarely enjoyed the range they gave to the women with low lives. From the garrulous shrew who rides a tonga or a stunning call girl with a heart of gold, the women in Salim-Javed world were no one’s fool. So thought-through that every last one of them could easily be launched into a spin-off of her own. Be that as it may, it struck me that the documentary arced their electric brief rise as an exposition to the central drama of their fall. Without intending it, perhaps, their tale became a cautionary tale of how the arrogance of writers ends up as an Icarian tragedy. Asking for fair visibility and remuneration can result in secret hostility and treachery. The industry, it looks like, had the last laugh as their powers waned. No contemporary screenwriter was happy to note that insight.

It has been a year since the industry has been in a slump. It doesn’t need nuance to tell you we are here because we choose actors over stories. Nobody nourishes the writers, while everybody overwaters the actors. In any film promotion, we repeatedly hear directors only extol their actors and develop selective amnesia about acknowledging the writers or every other collaboration with cinematographers, editors, or production designers. Repeatedly, we hear the pranks the actors played on the set during the shooting of a film. How often have I held my breath to listen to an actor acknowledge the writer who wrote the line from a profoundly personal experience that dazzled the screen. I am almost always disappointed.

Whenever the industry winter comes, it is the coldest for its writers with no one in their corner. History is rife with the best screenwriters waging contrarian situations at all times of their lives. Robert Towne, the writer most known for lead-writing Chinatown (1974), was fighting a bitter fight for better credits on his film The Two Jakes (1990), while also being acknowledged for his uncredited polishes on the script The Godfather (1972) by director Francis Ford Coppola in his Oscar acceptance speech, “Vito telling Michael, ‘I never wanted this for you’ in the garden? That wasn’t Puzo.” Even after being the stupendous writer that he is, we know that Charlie Kaufman still gets mad at Hollywood for struggling to finance his latest projects as a director.

“It has taken more than half the time since the invention of cinema to make the invisible visible in the apologetic mentions of screenwriters that made the films possible through their thoughts and politics, their lived experiences and their worldview, their personal lives pouring into the celluloid. And we still struggle daily to fight for the writer’s fundamental rights. At the SWA (Screenwriters Association), efforts lasting over two decades have yet to result in getting a Minimum Basic Contract passed off from the Producers Guild India. The demands of the writers ensuring basic dignity have been interpreted as radical, greedy or exploitative by the powers to be. While the non-Mumbai writers are still working without contracts or abysmally low wages, we are often asked what our stand is about including generative AI in screenwriting in India. It sounds petty for a privileged writer like me to protest about AI snuffing out my individuality and voice when the writer with even lesser means is still dealing with gross issues like arbitrary terminations, abrupt pay cuts and credits that are diluted as per the producer’s prerogative.

While things have been bleak, writers like Varun Grover and Juhi Chaturvedi have been our North stars, shining remarkably well as screenwriters in collaborations noted for both cinematic and philosophical reach. In Masaan (2015) and October (2018), Grover and Juhi revealed their authentic voices while amplifying their director’s vision. In both films, we can see how the director’s gaze is omnipresent, but the text is not laden with an either/or struggle between the writer and the director. Now that Varun has debuted as a director and Juhi’s film as a director is reportedly also on the cards, I wonder if it is true that a writer with a deeper quest for creative integrity and control may have no option but to move to direction.

While one may never know the right answer, I hope the decision to direct a film doesn’t always emerge as a rage against the machine. That ball is too blazing and hot and impossible to hold on to forever. In an ideal world, the only reason a writer should direct is because they want to, like American actor-screenwriter Greta Gerwig, who did it because she always wanted to and because she thought it was time. Not because they have to or won’t matter. It takes a writer to know that the quest for creative integrity on paper is a complete and wholesome life goal while pursuing power is a set of diminishing returns.

Atika Chohan is a Mumbai-based screenwriter and has co-written films such as Chhapaak, Guilty, Agra, Ulajh and Margarita with a Straw.