To make tteokbokki, you begin with rice cakes – chewy, dense, white cylinders – that refuse to soften easily. You soak them, coaxing their stiffness into pliancy. Then comes the fiery red sauce, followed by gochujang, sugar, soy, and perhaps, a flick of garlic. The secret is in the simmering, which allows the sauce to cling. The result is both sweet and scorching, half-pain, half-pleasure. It is the kind of dish that makes your eyes water even as you keep eating.

Around six years ago, I was two years into what was supposed to be the beginning of my adult success story — a stable job, a neat apartment, an inbox that hummed with purpose. On paper, everything was fine, but inside, I felt like I was dissolving.

One day, I confessed to a friend that I thought I might be depressed. She laughed lightly and said, “You are not depressed. Depressed people can’t move. They don’t even know they are depressed.”

I went home that evening and wondered if maybe she was right, and that my ability to shower, smile and function, disqualified my suffering. I recall pouring instant noodles into a pot and watching the water boil — the bubbles rising, bursting, and reforming. I remember thinking, maybe this is what I am — not broken, just boiling beneath the surface.

Was my ability to perform well at work proof that I was not unwell, or was it simply evidence of how well I had learned to perform wellness? I did not yet have the language to define what I was feeling, a sort of muted ache of functional disrepair. The kind that hides beneath competence, that looks like “doing fine” to everyone else.

For many modern women, survival itself has become a kind of performance art. We wake up and perform functionality for an audience of colleagues, friends, family, and sometimes, even ourselves. We smile in WhatsApp messages, type with enthusiasm, and end emails with “best” when what we mean is “barely holding it together”. We move through our days as if on stage, pretending to be efficient, composed, and endlessly capable. Beneath the choreography, we are exhausted. It was not just me. I began to see that many of us perform our own wellness.

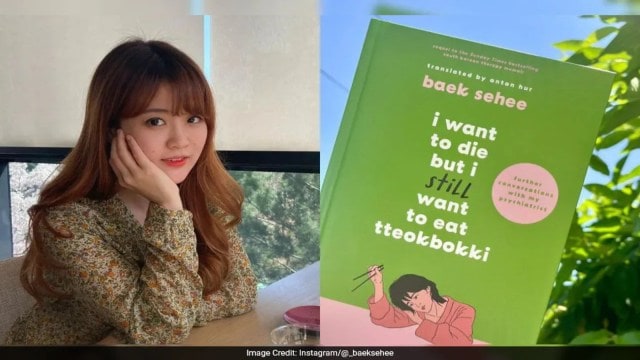

Se-hee, who died last week at the age of 35, captured this duality in her book that comprises talks with her psychiatrist. Her psychiatrist tells her that she is running on a hamster wheel of self-improvement, trying to escape depression through effort, only to fall deeper into it. Her life, like so many of ours, was a carousel of comparison: Work harder, look better, seem happier, care more. The irony is that the pursuit of being “fine” is what so often makes us unwell.

Women today carry the weight of expectation in invisible ways. We must be competent but not cold, ambitious but not aggressive, empathetic but not exhausted. We must “self-care” without appearing indulgent, and “set boundaries” without being accused of selfishness. We must want children but not too early, love our jobs but not too much, and above all, never, ever drop the performance. Women must always manage — emotions, households, careers, and ourselves. When we falter, the failure feels personal, not systemic.

Se-hee understood this pressure. She examined her sadness like a project, desperate to fix it, to remain efficient even in pain. Her doctor reminds her that sometimes the goal is not progress, but presence. Yet presence, in a world that rewards constant self-optimisation, is the hardest thing to sustain.

When Se-hee writes about recording herself during social interactions to analyse her behaviour later, it sounds absurd, until it doesn’t. Many of us do it in other ways — replaying conversations in our head, rereading texts, editing ourselves mid-sentence. We are so accustomed to watching ourselves from the outside that we forget how to inhabit our own skin.

I think often of that friend’s comment, the certainty with which she defined depression by immobility. But what if functionality is simply another mask? What if the act of keeping up appearances – of staying composed, productive, pleasant – is the very thing that prevents us from healing?

Se-hee’s work showed that endurance is not the same as thriving. In her death, readers mourn not only the author, but the mirror she offered us. I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki became a kind of shared confession: I want to live, but I don’t know how.

Maybe the lesson lies in that bowl of tteokbokki. To eat it is to acknowledge both pleasure and pain. Or perhaps the answer lies in the pot — you stir, you taste, you add more gochujang if it is too bland, more sugar if it is too fiery. You do not aim for perfection, but balance.

Modern womanhood is a recipe that is constantly being rewritten. Some days we simmer. Some days we boil over. But even in the middle of that heat, there is the quiet, defiant thought – what Sylvia Plath wrote all those years ago – I am, I am, I am.

Years later, I no longer think of my lows as disqualifications. They are proof that being alive is not a static state. We can be both capable and cracked. We can want to die and still crave something beautiful and red and burning on our tongues.