As the first anniversary of Russia’s Ukraine invasion approaches, two contradictory trends are playing out. One, there is renewed military action along a frontline that was largely frozen during the winter weeks. Russia has already launched a military offensive in the Donbas region and Ukraine’s counter-offensive is said to be around the corner. Amid the military escalation, there is also “talk about talks” between Kyiv and Moscow. We have entered a new phase in the war, when more intensive fighting will take place along with some high-voltage peace diplomacy.

Beijing has now stepped into this minefield. In a “peace speech” this week, President Xi Jinping is expected to unveil a set of proposals to bring the war to an end. President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has travelled to Kyiv for the first time since the Russian invasion and is addressing the “Bucharest Nine”— a group of Central European countries that form NATO’s eastern flank and have the greatest stake in the way this war ends. Members of this group were either part of the Soviet Union or in the Soviet sphere of influence after World War II. The war in Ukraine is no longer just about Europe. The UN General Assembly is debating a resolution to be adopted this week on a “comprehensive, just, and lasting peace” in Ukraine.

Xi’s initiative is well-timed. There is also interest in India’s potential contribution to peacemaking. When German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni arrive in Delhi in the coming days, the question of ending the war in Ukraine will be at the top of their discussions with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The gathering of G20 foreign ministers in Delhi next week will also provide the broader international context for an Indian reflection on the challenge of peace in Ukraine. Both Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken will be in Delhi. India will also host a round of consultations between the foreign ministers of the Quadrilateral forum on the margins of the G20 ministerial. If there was ever a good diplomatic moment for India to step out more boldly on Ukraine it might well be now. Although Delhi does not overestimate its role in promoting peace, there are opportunities for making important contributions on the margin.

During his swing through Europe last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was preparing the ground for the launch of Xi’s peace initiative. Wang is consulting with key European powers — Germany, France, and Italy – as well as Ukraine. In Munich, he met Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba. He is in Moscow right now for consultations with Russia. Beijing has long had good relations with Kyiv and has no intention to sacrifice Ukraine on the altar of its special partnership with Russia. Nor does it want to undermine the alliance with Russia. Beijing’s Ukraine diplomacy, then, is about finding ways to navigate the contradictions between Kyiv and Moscow, protect Chinese interests, and expand its strategic influence in Europe.

Given that Beijing is now Moscow’s closest and most valuable partner, Chinese ideas on peace are getting a good hearing in Europe. The Biden Administration has long been pressing China to encourage Russia to end the war. But Washington is also wary of Beijing’s power play. At the Munich security conference, Blinken accused China of preparing to sell arms to Russia even as it talks peace. China is also seen as using the peace plan to reset the damaged relationship with European states and drive a wedge between the US and Europe. The war is an opportunity for Beijing to emerge as an active shaper of the European security order. Until now, Beijing has been viewed as an adjunct to Moscow in Ukraine. China might now want to reposition itself as a peacemaker between Russia and Europe. Russia’s weakened position and its growing dependence on China have, arguably, improved Xi’s leverage in the European crisis.

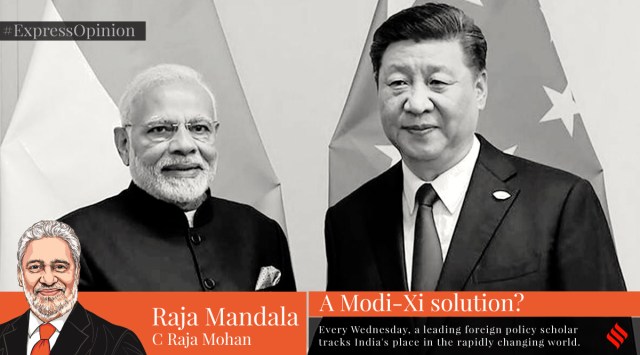

That opportunity might also exist for Delhi. As two countries friendly to Russia, there has been widespread expectation that Beijing and Delhi can nudge Moscow towards a more reasonable posture. While China and India have not condemned the Russian invasion, they have been careful not to endorse it. At the Samarkand summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation last September, Xi and Modi expressed their discomfort at the war. Both leaders also expressed their strong opposition to the use of nuclear weapons in the conflict.

To be serious players, though, Beijing and Delhi will have to go beyond general concerns about war to suggesting concrete steps towards peace. On his part, Wang said China’s plan would emphasise the need to uphold the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity and the UN Charter. Wang added that the legitimate security interests of Russia needed to be respected. Squaring Ukrainian sovereignty with Russian security concerns framework is the most important element of any peace settlement. But reconciling the two is also the hardest part of any diplomatic effort. For Kyiv, sovereignty is about reversing the Russian occupation of eastern Ukraine and Crimea and seeking long-term security guarantees from third parties. For Moscow, security is about limiting the sovereignty of Ukraine and its neighbours to the west. “Limited sovereignty” for its neighbours has been an enduring theme of Russian international relations. Preventing the presence of other powers on its periphery is also at the heart of Russian security concerns.

Consider two other key ideas in a potential peace process. One is a “ceasefire”, which must be the first step towards any political solution. Many in Europe believe a ceasefire at this moment will help Russia, leave it in control of occupied territories, give it a chance to recoup and renew its attacks against Ukraine. Ceasefire must, then, be associated with some broad understanding of the nature of peace.

The idea of trading Ukrainian territory for peace is a common theme. But which nation wants to give up territory for the sake of peace with an aggressor? Will Delhi accept Beijing’s territorial demands on Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh for peace with China? Many Europeans strongly believe that no “just peace” in Ukraine can be founded in rewarding the aggressor and punishing the victim.

While the room for diplomacy in Ukraine is growing, the barriers to peace are very high. That is not stopping Xi from trying his hand at peace in Ukraine. Nor should PM Modi be daunted by the massive obstacles. For both leaders, promoting peace in Ukraine is also about recalibrating their great power relations and reordering their Eurasian geopolitics.

The writer is senior fellow, Asia Society Policy Institute, Delhi and contributing editor on international affairs for The Indian Express