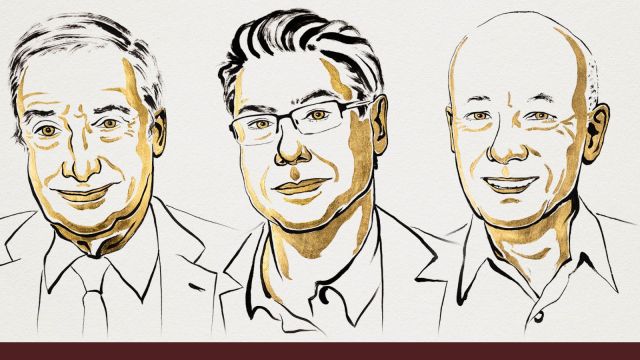

In Hindu mythology, Shiva performs the tandava — the cosmic dance of creation and destruction, where old worlds are unmade so new ones may emerge. Joseph Schumpeter might not have known this imagery, though many Germanic intellectuals that preceded him did; yet his idea of capitalism’s “perennial gale of creative destruction” echoes it perfectly: Progress as rhythm, innovation as both builder and destroyer. A question this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, awarded to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, poses is whether artificial intelligence marks just another turn in that eternal dance, or a fundamentally new movement.

The Nobel committee’s timing seems deliberate. As large language models reshape industries and AI becomes the defining technological question of our age, the Prize honours three economists who explained how growth springs from innovation — and what allows it to endure rather than fade. Mokyr, the economic historian, asked why the Industrial Revolution succeeded where earlier bursts of ingenuity failed. His answer lay in a marriage: Between propositional knowledge, knowing why things work, and prescriptive knowledge, knowing how to build them. Before the Enlightenment these realms rarely met — artisans mastered craft without theory, philosophers theorised without machines. Their union in 18th century Britain created a feedback loop where each discovery seeded the next. But Mokyr showed this required more than great inventors: It needed a class of skilled mechanics to translate blueprints into tools, and a society open enough to let new ideas defeat vested interests.

Now consider AI through their lens. Earlier general-purpose technologies — the steam engine, electricity, the internet — transformed production but left knowledge creation to humans. AI is different because it touches the act of thinking itself. It accelerates both discovery and application, compressing the gap between knowing why and knowing how. Algorithms that predict protein structures or design new materials automate what Mokyr called the dialogue between propositional and prescriptive knowledge. His virtuous cycle, once paced by human trial, now spins at machine speed.

But is this a difference of degree or of kind? Gutenberg’s printing press, after all, also revolutionised knowledge diffusion. Each generation thinks its revolution unique; history reminds us that most are variations on enduring themes. Still, AI’s reach into cognition — the “creative destruction of intelligence itself” — feels somewhat unprecedented.

The laureates’ work helps frame three questions for our era. First, the structure of competition. Aghion and Howitt found innovation thrives at intermediate levels of rivalry — too little, and monopolists grow complacent; too much, and returns to R&D vanish. Today a handful of technology giants dominate AI, protected by vast data and compute advantages. Are these scale economies efficient inevitabilities or barriers choking future upstarts? When Google, Microsoft and OpenAI can deploy tools to billions overnight, the space for creative destruction narrows.

Second, the social cost of acceleration. Creative destruction, as the phrase itself concedes, creates losers. Jobs disappear faster than new ones form; entire sectors must reinvent themselves. The policy goal cannot be to freeze change but to cushion its impact — protecting workers, not specific jobs. That means portable benefits, serious retraining, unemployment insurance fit for a world where skills expire in a few years rather than decades. Without such buffers, the dance tilts more to destruction without commensurate creation.

Third, the question of institutions. Mokyr showed that growth flourishes primarily in societies willing to accommodate change despite resistance from entrenched power. The Enlightenment succeeded because parliaments, academies, and open forums channelled conflict into negotiation. Do we have equivalent institutions today? Our regulatory frameworks increasingly fragment the global knowledge space — data localisation here, failure of multilateral institutions there. Some oversight is essential, but if every innovation must navigate protectionist thickets, without effective global referees, the very feedback loop that sustains progress could stall.

Economic history counsels humility. Predictions of technological destiny are usually wrong. The internet was once dismissed as a fad; nuclear power was to make electricity too cheap to meter. AI may well transform everything — or not quite as much as its prophets claim. Even still bubbles can be useful: exuberant capital funds infrastructure that endures beyond the hype, as fibre-optic cables from the dot-com boom still carry today’s data.

For India, the questions acquire special urgency. Unlike the United States, it cannot throw capital at the frontier, nor can it, like China, command a state-directed AI push. But sitting out the revolution would be costlier still. India’s advantage lies not in wealth or resources but in what Mokyr called mechanical competence — the ability to turn ideas into applications. Its engineers, coders, and Global Capability Centres already translate global knowledge into usable systems. The task is to build the institutions that amplify this strength: invest heavily in technical education, keep research access open, regulate without smothering, and resist the lure of protectionism that would cut Indian talent off from the frontier. India may not train the largest models anytime soon, but it can shape the smartest scalable uses of them; and eventually foundational models will come too.

Ultimately, this Nobel reminds us that sustained growth is fragile. Stagnation, not dynamism, has been humanity’s default. What breaks it are institutions that reward innovation, protect experimentation, and flex with change. AI will almost certainly power growth; whether it deepens human flourishing depends on the choices we make around it. Will we preserve openness to new ideas, the competition that keeps progress alive, and the safety nets that make destruction bearable?

Shiva’s dance continues. The challenge is to build institutions worthy of its rhythm— flexible enough to adapt, strong enough to endure, humane enough to ensure that the creative destruction of intelligence itself enlarges not only our capacities but our compassion.

The writer is assistant professor of economics at Cornell University and co-author of Breaking the Mould: Reimagining India’s Economic Future