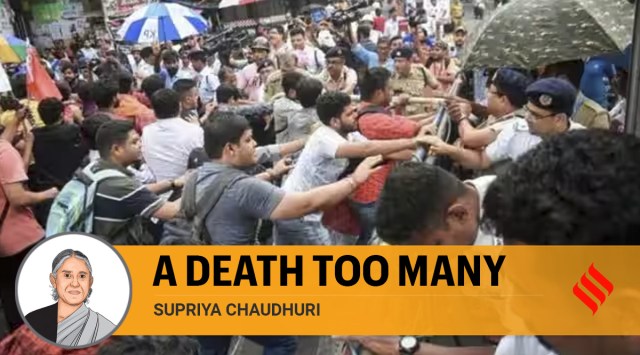

On the night of August 9, a first-year student fell or was pushed to his death from a hostel block at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, probably after being abused by his seniors. This horrific crime has aroused extraordinary public outrage, directed both at the administrative failure and at the sadistic cruelty masquerading under the obsolete euphemism, “ragging”.

It turns out that more or less everyone in the university community was aware of the bullying and abuse that routinely took place at the men’s hostel. The victim, a minor, had shared his fears with both family and fellow students, though without making a formal complaint. He received neither counselling nor advice from faculty, departmental seniors, or the university’s student welfare board, and was left to deal with the trauma of his first few days in the hostel alone.

In all these ways, Jadavpur University failed him in its duty of care. This criminal failure indicts an institution that has prided itself on excellent teacher-student relations and community spirit. It also indicts society’s neglect of a culture of torture and abuse in which its members were complicit, and the normalisation of such behaviour as a university coming-of-age rite. Fostered by official apathy or patronage, ragging is condoned by the gangland honour code of the student body. Despite official campaigns against the practice, ragging has never been an issue in campus politics. Far less does it figure in the larger political arena, where ideological debates are similarly oblivious to gender discrimination, rape, domestic abuse, and hate crimes, all generated by the same psychopathology of violence linked to the exercise of power.

Yet on campus at least, there was no excuse for institutional apathy. The immense social toll taken by this culture of abuse had reached critical mass when in late 2006 the R K Raghavan Committee, set up by a Supreme Court directive, had recommended that “raggers” be treated as criminals, that a section on ragging, on the lines of the anti-dowry laws, be introduced in the Indian Penal Code, that the burden of proof be on the accused rather than the victims (as in the existing rape provisions), and that a national anti-ragging helpline be set up.

In March 2009, Aman Satya Kachroo, a 19-year-old medical student at Dr Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College, Himachal Pradesh, was beaten to death by hostel seniors. Initially, college officials passed off his death as suicide, and it was only after the autopsy revealed the extent of Aman’s injuries that his four assailants, Ajay Verma, Naveen Verma, Abhinav Verma and Mukul Sharma, were criminally indicted by the Kangra police. They were sentenced by a fast-track court to only four years of rigorous imprisonment, but even so, they were released in August 2012, like Bilkis Bano’s rapists, for “good conduct”. This leniency was denounced by Aman’s father, Rajendra Kachroo, who had initiated a countrywide anti-ragging movement in memory of his dead son. Speaking in the Rajya Sabha, Rajendra Kachroo pointed out that in the three years since his son’s death, no less than 35 young students had died by “suicide” across the country as a result of torture and abuse in educational institutions.

Like the December 2012 gang rape and murder, Aman Kachroo’s death, just another casualty in a long and horrific list, caused a national outcry. On June 8, 2009, the Supreme Court directed that the Raghavan Committee recommendations be implemented immediately, that the UGC finalise its anti-ragging regulations, and that “freshers should be lodged in a separate hostel block, wherever possible, and that seniors’ access to freshers’ accommodation should be strictly monitored by wardens, security guards and college staff”.

The Aman Movement was subsequently charged with creating a national database to monitor incidents of ragging. Its reports indicate that the largest number of incidents are from Uttar Pradesh, closely followed by West Bengal. This comes as no surprise. Over the past 50 years, horror stories of mental, physical, and sexual violence have reached us from premier residential institutions in this state as elsewhere. Many families, mine included, had at least one child who could confirm the reports from personal experience of both mental and physical abuse.

In a moving personal testimony I read recently, a friend describes the tragedy of her brother’s unexplained death, shortly after he entered Bengal Engineering College, Shibpur, nearly 40 years ago. Similar questions are raised by the recent death of Faizan Ahmed, a third-year student at IIT-Kharagpur, and of 19-year-old Souradeep Choudhury, who died after falling from the 11th floor of his hostel in an engineering college in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh.

There have been periodic attempts to break this cycle of abuse and silence. After the Supreme Court directive of 2009, Jadavpur University resolved to place first-year students in a separate hostel. Weeks of protest by all student unions followed. During the Arts Faculty Students Union sit-in at the Undergraduate Arts building, my colleagues and I asked their leaders why they were objecting to this safety measure, but were met with evasive formulas about “social interaction”. As a member of the Anti-Ragging Committee, I recommended action against students found guilty of ragging, and was roundly abused not only by the perpetrators but by their fellow students who agitated for months against any punishment.

For several years following the Supreme Court judgment, anti-ragging vigilance was stepped up on campus, and the Anti-Ragging Squad made midnight visits to hostels to rescue victims and identify perpetrators. In September 2013, two fourth-year students found guilty of ragging were suspended for two semesters. Students supported the raggers through a gherao of the Vice-Chancellor, Souvik Bhattacharyya, and even the Deans suggested that the penalty be reconsidered. Bhattacharyya resigned shortly afterwards, and his successor Abhijeet Chakrabarty referred the case to the Chancellor for judgement.

Why, we might ask, do students act against their own interests, and faculty and administrators look away from, if they do not actually connive in, an abusive practice? I would suggest that it is because we have failed to identify “ragging” for what it is. It is not a culture confined to educational institutions, where students enact initiation rites in ‘protected’ spaces. Fundamentally, it is a perversion of power, the same kind of sadistic violence that is publicly or privately manifested through bullying, sexual assault, domestic abuse, rape, torture, or lynching. Such violence must be addressed by society as a whole, in terms of the human right to dignity, safety and freedom from assault. As civil rights and gender activists have shown, institutional spaces are answerable to justice and law. Failing to safeguard them is to fail ourselves.

The writer is Professor Emerita, Jadavpur University, Kolkata