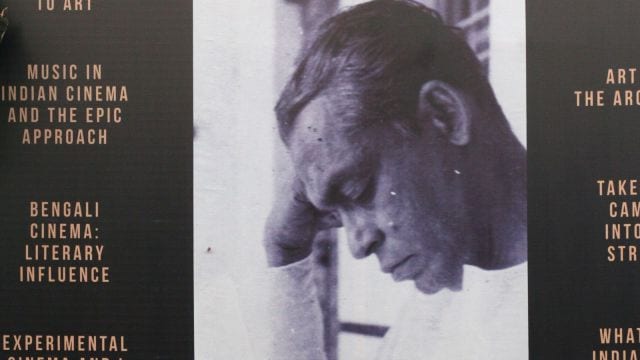

Immensely talented but self-destructive, Ritwik Ghatak could well have been a Shakespearean tragic hero. But his art and cinematic legacy endure. Mainly because his students-turned-filmmakers and the cinephiles who adore him — and they do so deeply — have ensured that the world celebrates his genius posthumously.

Born in Bangladesh on November 4, 1925, to Rai Bahadur Suresh Chandra Ghatak, a district magistrate, and Indubala Devi, the filmmaker would have turned 100 today. The auteur, who never received wide recognition during his lifetime, died at the age of 50. Throughout his life, he grappled with financial troubles, professional disappointments and, later, alcoholism.

His debut film, Nagarik, which many believe could have pioneered the alternate cinema movement in India, was completed in 1952 when he was just 27 — three years before Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali captivated audiences at home and abroad. But Nagarik was released only in the late 1970s, after Ghatak’s death on February 6, 1976.

In his own words, Ghatak “strayed into films down a zigzag path”. He was associated with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and the Communist Party of India (CPI), before he took a full-fledged plunge as a filmmaker. These experiences, along with his sense of being alienated from his homeland since his family shifted from Bangladesh to Calcutta when he was 19 went on to decide the tone and tenor of his cinema.

Even though in the peak of his career, Ghatak’s alcohol addiction became a hindrance in his filmmaking journey, he still made eight features and 10 documentary films. Today, most of them, including his acclaimed Partition trilogy, which comprises Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha (1965), known for their poetic exploration of post-Partition trauma and dislocation are among the finest examples of cinematic excellence. His other prominent features are Ajantrik (1958), Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973) and Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974).

Over the decades, several labels have been used to describe Ghatak — enfant terrible, underrated auteur, eccentric genius, among others. Yet, the truth is that even when it seemed like he was using methods that broke cinematic conventions, Ghatak was actually forging a language of his own. His approach helped him connect profoundly with both his students at FTII, Pune, and his audience decades after his demise.

Ghatak’s legacy was cherished and carried forward by his students at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. There, he taught direction between 1962-67, set the curriculum and made a huge impact on a generation of filmmakers. Talking about his unusual teaching method, the late PK Nair, former director of National Film Archives of India (NFAI), once told me about how Ghatak woke up his students at 4 am one day and took them to the Shantaram pond on the campus to watch the sun rise and study light. Prominent Kolkata-based author, the late Nabarun Bhattacharya, who was Ghatak’s grandnephew, too recalled to me how the filmmaker ignited his curiosity and introduced him to literature and music when he was a young boy.

In an interview, Ray once acknowledged Ghatak’s distinct sensibility, saying, “He is one director whose style is greatly influenced by Sergei Eisenstein’s work (Battleship Potemkin). His style and approach are very different from mine. Therefore, unique.”

Some years ago, while introducing Ghatak’s A River Called Titas, Martin Scorsese remarked that few filmmakers were denied recognition during their lifetimes as Ghatak was. “Ghatak had an extremely refined vision of cinema,” Scorsese said. “His pictures were both visually and thematically dense and layered. None of them were popular successes, and he never found the mass audiences he wanted. Ghatak did, however, inspire an entire generation of independent Indian filmmakers — as a teacher and through the example of his work.”

Most of the recognition for Ghatak’s work came years after his death – Ghatak himself had foreseen this. By British film critic Derek Malcolm’s account, “the first time a group of Western critics was able to look at the body of his work was at the Madras Festival in January 1978. The prints were tattered, the subtitles virtually unreadable… But the impact of the films on all present was considerable. Here, we all felt, was a passionate and intensely national filmmaker who seemed to have found his way without much access to the work of others but who was most certainly of international calibre. Two years after his death he was already a legend.”

As Ghatak’s birth centenary celebrations put the spotlight back on him, the perfect tribute would be to examine what he stood for; how he questioned the status quo and urged others to do so; how he blended the personal and the political; and how he desired to communicate with the masses.

alaka.sahani@expressindia.com